Boarded up storefronts and battered nerves: A day in the life as Americans vote in the 2020 election

As a pandemic raged, gun sales soared and buildings were sheathed in protective plywood, Americans slipped on face masks, wrestled with their anxieties and went to vote on the last day of the most bitter and surreal election in generations.

Amid the clamor — and regardless of political persuasion — many voters sought to settle frayed nerves and find peace.

In Florida, a warehouse worker asked if he could come in on his day off to avoid nervously watching election coverage at home. In Utah, an emergency room doctor from California who has treated dozens of COVID-19 patients cast his ballot early and escaped into the majestic canyons of Zion National Park.

“The stress is at a different level,” said Aarrie Blackman, a 27-year-old first-time voter who was up at 3 a.m. Tuesday, wondering whether she might encounter violence when she went to her polling place south of downtown Atlanta. She sought comfort by eating an English muffin and binge-watching a favorite sitcom, "Living Single."

It was as if a great storm had nearly passed. After months of protests, fresh graves and warnings about possible civil unrest, there was a yearning for calm even before the outcome was known.

The nation did its duty, took a breath and waited.

As the sun rose in Orlando, Fla., 24-year-old Kim Candelario found herself lying in bed wide awake.

It was two hours earlier than she had planned to rise. But she saw no reason to wait. She skipped breakfast and walked 20 minutes to Shiloh Baptist Church, arriving shortly after polling opened. Clad in a blue surgical mask and gray pajamas, she voted for Joe Biden.

Candelario, who was born in New York and whose family is from the Dominican Republic, registered to vote six years ago but had never before cast a ballot.

It was different this time. She was angry. A call center worker who handled complaints from Visa and Mastercard customers, she spent her 12-hour shifts talking to Americans who were out of work and couldn't pay their bills.

As a Black woman with sickle cell anemia, which put her at higher risk if she became infected with the coronavirus, she had spent much of the last eight months locked inside her apartment, stewing about President Trump's handling of the pandemic.

Candelario had tried to vote early, but her schedule made it nearly impossible. She opted against an absentee ballot because she didn't trust the U.S. Postal Service. It turned out to be for the best.

“I’m glad I didn’t come in before,” she said after placing an "I voted" sticker on her chest. “To vote today feels patriotic."

Nearly 100 million ballots had already been cast nationwide — almost 75% of the total votes in 2016 — before the polls opened Tuesday.

Kevin Barthold, a union member in a suburb of Detroit, voted in person several weeks ago for Trump. But he still took off work to carry out what has become his ritual on election day: slow-cooking 100 pounds of paprika-seasoned pork.

“We will just wait and see how this meat and this election turn out,” Barthold said with a grin as his chocolate Labrador, Rocky, sniffed at the wood smoker.

Barthold, 58, says Trump is a candidate who "understands guys like me."

“He’s not the most politically correct, and that’s fine, you don’t have to play by the rules," said Barthold, who particularly likes Trump's opposition to gun restrictions.

A field technician for AT&T, Barthold voted for President Obama in 2008 but was turned off by partisan divides between Congress and the White House.

“They would just bicker,” he said, adding that he thinks former Vice President Biden was part of the problem.

On Barthold’s suburban street — one with manicured lawns and high wooden fences — both Trump and Biden flags dot yards that on recent mornings have been ghosted by a light frost. After cooking his pork, he planned to freeze it and give some to his neighbors for winter — no matter their politics.

“We all just want what is best for this country," he said.

More than a thousand miles south, in the upscale Houston suburb of Sugarland, Louis Carballo also cast a vote for Trump.

“A lot of pollsters make the statement that minorities vote Democrat," said Carballo, 74, a retired architect who was born in Cuba and has always voted Republican. "We have our own minds."

He doesn't buy complaints from Democrats about systemic racism. The father of a Houston police lieutenant, he chafes at calls for defunding law enforcement.

As for the pandemic, he's tired of lockdowns. Carballo wore a mask to vote but says he refuses to live in fear of the virus — still going out to eat with his wife and visiting friends in other cities.

But the pandemic — and the 232,000 American lives it has claimed — casts a long shadow on the election.

In El Paso, a West Texas city of 680,000 along the Mexican border, one of the worst coronavirus outbreaks in the nation left many scared to leave their homes.

As the midday sun beat down on the jagged mountain range that cuts through town, officials announced a record number of active coronavirus cases (19,201) and a record number of patients in the ICU (293).

Things had gotten so bad that patients were being airlifted to other Texas cities, and there were rumblings about how the virus was on track to kill more people in El Paso this year than cancer and heart disease.

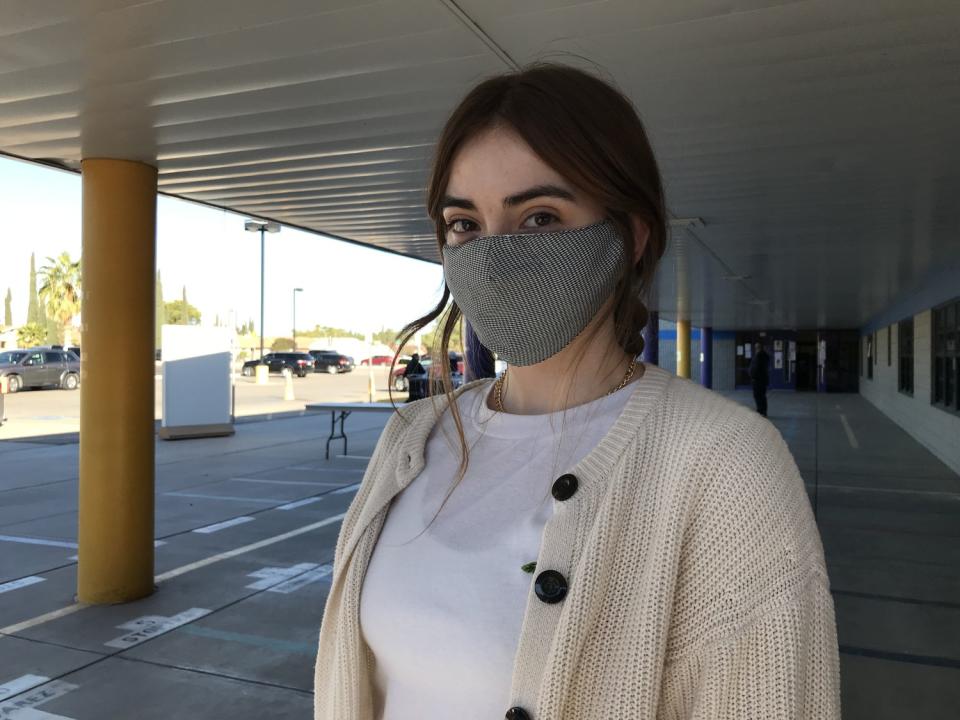

Margaret Cataldi, a 20-year-old junior at the University of Texas at El Paso, was determined to keep voters safe. She volunteered as a poll worker at an elementary school near her home, scrubbing voting booths every few minutes with alcohol wipes.

Cataldi, who wore a long skirt, boots and a gingham mask, said she had been politically aware since at least 2016, when she and her high school friends were inspired by candidate Bernie Sanders.

But her real awakening came in August of last year, when a 21-year-old white man drove 650 miles to an El Paso Walmart and used a semi-automatic rifle to kill 23 people. Police say the man, who had posted an anti-immigrant screed online, confessed to the crime, saying he was targeting "Mexicans."

Cataldi, who worked at the mall next door, was traumatized by the shooting — but also moved to action.

“He came to kill us — to kill brown people — because he doesn’t think that we should be alive,” said Cataldi, whose mother was born across the border in Juarez, Mexico.

She blames Trump for the attack.

“Just as I was radicalized by his presidency, he has radicalized people on the other side as well,” she said. “Now I’m determined to see this fascist government out of office.”

She had begun tracking right-wing extremist groups online and was anxious about the prospect of post-election violence. The last six months had been dominated by late-night "doomscrolling" and melatonin pills to help her get to sleep.

“I’ve cried about it many times,” she said. “We’re in a very dark place as a country, and I’m worried about my community being targeted again."

On the outskirts of Seattle, another poll worker had been motivated by fear and anger to volunteer.

Dr. Peggy Hutchison, a 69-year-old physician who helped lead the coronavirus response for a Seattle-area hospital system, had been tasked with monitoring a ballot drop box, directing traffic and watching for voter intimidation. Not even a soaking rainstorm could stop her.

The Seattle area was one of the first regions in the country to be hit by the coronavirus, and Hutchison couldn't shake memories of that early chaos: doctors who stripped down to their underwear in the garage in order to protect their families; a medical worker who fell seriously ill for three weeks; colleagues layering cloth masks over paper ones because there weren't enough N95 respirators.

“The administration’s response to physicians and scientists is abhorrent,” she said. “It lacks insight ... it demeans them.”

Hutchison and her husband both voted for Biden several weeks ago via a ballot drop box near their Bellevue home. But on Tuesday, her role was to help thousands of last-minute voters “follow through.”

As the winds picked up, the rain came down and the sky began to darken with night, Hutchison said she would stand guard until the last ballot was cast.

Not everybody had been so rattled by the election.

For Joel Clark, a tanned, bearded 72-year-old with long, gray hair poking out from a "Vietnam veteran" cap, 2020 hasn't been a particularly unsettling year.

A former construction worker and prison guard, he said he wasn't worried about the pandemic, although he doesn't like being told to wear a mask. ("It’s against the Constitution.") He also wasn't worried about post-election violence hitting his town of Prineville, in a rural swath of central Oregon, because there are "way too many people walking around with pistols and AR-15s."

He long regarded Washington, D.C., politicians and bureaucrats as clueless, an impression confirmed years ago by a highway inspector who reviewed an asphalt paving project that Clark was directing as foreman. The inspector described a phone call from an official in Washington who wanted to know why a highway project called for so many cattle guards, the grills placed in roadways to impede livestock.

“‘How many guards, and what sort of equipment do they need?’ the guy asked,” Clark said. “He thought they were [human] guards who stood there watching for cattle.”

Because of experiences like that, Clark has been married more times than he’s cast a ballot. He voted for Trump twice. He likes the president's business background and law-and-order stance. He supports him for being tough on cities such as Portland, where violence has flared during protests.

On Tuesday, Clark filled in his mail-in ballot while sitting in his truck outside a courthouse in downtown Prineville. He voted for every Republican candidate and against a state initiative that would legalize psychedelic mushrooms for therapeutic use. (“You really want to see your kids running around on that stuff?”)

Then he walked over and slid his envelope into a ballot box. Just in time.

Clark, who watches Fox and listens to conservative podcasts, wasn’t planning to follow election coverage Tuesday night. Instead, he would be helping his daughter fix up her house.

“All that would do would irritate me,” he said. “I’ve got to hang a door.”

Linthicum reported from El Paso, Kaleem from Orlando and Lee reported from Canton, Mich. Times staff writers Jenny Jarvie contributed from Atlanta, Richard Read from Prineville, Emily Baumgaertner from Los Angeles and Molly Hennessy-Fiske from Houston.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.