Bob Hill: How a 100-year-old Kentucky veteran's baseball hero taught him to fly

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

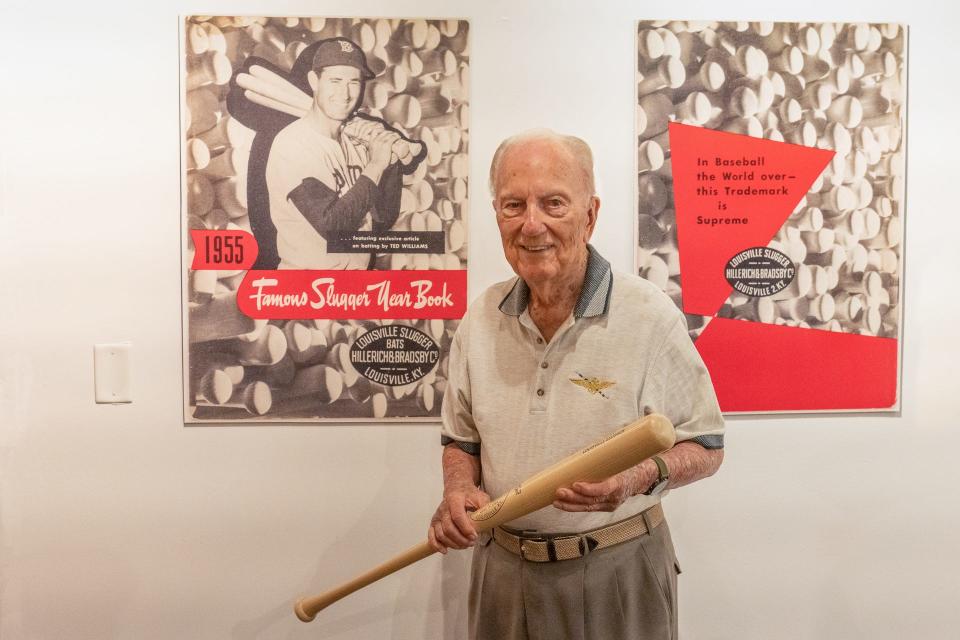

Paul Jones knew exactly what to do with the bat. Only a few months shy of his 101st birthday, a life-long baseball fan whose very full life story includes being trained as a WWII Naval Air Cadet by baseball legend Ted Williams, he was standing in the bat vault of the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory gently holding a Ted Williams model bat.

Jones grew up in Corbin Kentucky and never really got away from it. This was a time when every Appalachian coal camp town had its own baseball team; Corbin High School didn’t have one. It was the 1940’s, when away games were played over the mountains to Harlan County in Benham and Lynch. It was bringing your own equipment, everybody swinging a prized Louisville Slugger, about the only bat available. If you cracked it you taped it up and kept swinging.

At 16 he was the youngest guy on the town team, a natural second baseman, about 5 foot 9 and maybe 130 pounds. It was home-grown coaching. The ball fields dusty, mostly level with some wooden bleachers. Fun times with families, neighbors and townsfolk watching and supporting.

“Some of the coal camp teams paid pretty good,” he said. “I was never really that good. I just loved baseball.”

When he volunteered for Navy duty at age 20 in May 1943 he quickly jumped to 150 pounds and held it there for the next 80 years. The baseball fan in him had idolized Ted Williams, the Boston Red Sox legend who in 1941 batted .406. It was a record he embellished by going six-for-eight in a season final double header when he could have taken a season final .400 average by sitting out the games. It was a baseball story that found its way to Corbin.

“I almost worshipped him,” Jones said of Williams.

His Navy enlistment came with a boyhood dream of flying.

Early WWII was a very nervous time in American history with pilot training that lasted 18 to 20 months in aircraft and pilots not always up to the task.

“I just had an appetite for it,” Jones said of becoming a pilot.

He was soon stationed for Naval Air Force training in Pensacola Florida where it turned out his formation instructor – on some days flying at 200 miles-an-hour about six feet off his airplane’s wing - was Ted Williams, who had joined the Navy aviation service one year earlier in May 1942.

Over his 19-year baseball career, Williams had a .344 batting average, the highest ever in the live-ball era, with 521 home runs. He retired on Sept. 28, 1960 after hitting a home run on his final at bat. He could have hit many more. William’s career was interrupted with three years’ service in the Navy and Marine Corp during WWII, and parts of the 1952 and 53 seasons as a Marine pilot in Korea. Williams did not see combat in WWII, but, at his insistence, flew 37 missions in a F9F Panther jet in Korea, one ending in a crash landing after being hit by enemy fire.

All this bears repeating: During his WWII Naval pilot training, Paul Jones, a Corbin Kentucky baseball fan and strong admirer of Ted Williams, found himself flying in training formations side-by-side with Ted Williams.

Baseball legand Ted Williams taught him to fly

“When he found out where I was from he nicknamed me “Briar,” said Jones. “That’s all he ever called me, “Briar.” He was a great guy.”

In the six weeks they trained together Jones learned Williams was every bit as good a flight instructor as he was a baseball player. Constant attention to detail. Mistakes could be fatal.

Williams – go figure – was also a member of the Pensacola Naval Base baseball team. Cadets were not allowed on the team, but once a week, on his off days, Jones would work out with them.

“I took my glove with me when I went into service,” Jones said, “but I rarely got to use it.”

His best days were spent next to Williams in the outfield, or just playing catch with all the team members. Catch was and remains a universal baseball ritual, a time to loosen-up and catch-up. The players in even lines slowly tossing a baseball back and forth, the laughter, jokes and conversations, the “thwack” of ball in glove.

Repeat and repeat.

Jones eventually became a pilot, taking off and landing F6F Hellcat fighters from the 456-foot carrier deck of the USS Guadalcanal. He crashed once while practicing a carrier landing on marked ground.

“I’d look back over my shoulder after takeoff,” he said of his Guadalcanal experience, “and the deck looked like a postage stamp. After a few times it got easier.”

Baseball with the Corbin, Kentucky 'Railroaders'

He was discharged in November 1945 without ever seeing any combat. That used to trouble him, but now he considers himself lucky. He never saw or heard from Ted Williams again. He went back home to Kentucky to play baseball on the Corbin town team, once nicknamed the “Railroaders” with the L&N Railroad the biggest employer in town. He would play baseball until he was almost 40, by then managing more and playing less.

The Corbin Railroaders took on a dozen other town teams in 1946, going to the state finals only to lose to Pikeville. About 80 years later Jones still remembers the score of that game but, laughing a little, said he didn’t want to talk about it. Some consolation was he was named Kentucky All State at second base in 1946. The plaque is still on his wall.

Once settled back in Corbin he married Shirley Wallen Jones, a director of nursing in the local hospital, and took over as manager of the local furniture store his father and grandfather had started in 1922. He became very involved in Corbin civic activities and joined the Navy reserve. He purchased a Cessna 182 and flew it to various Navy bases around the country to help transfer Navy planes, many to an airplane “graveyard” in the desert near Phoenix. From 1955 to 1959 he began flying Naval jets. He said it was easy – a little classroom training and then get in the cockpit, hit the throttle and let it fly.

He was in the reserves more than 20 years. In a trip to the National Naval Aircraft Museum in Pensacola he counted 17 different planes he has piloted, included three jets. He sold the Cessna after 40 years and stopped flying when he was 82. He still drives his car.

Shirley Jones died of cancer three years ago after 55 years of marriage. They had no children. He very much misses her, lives by himself, walking two miles on his treadmill at least five times a week and going to local and Cincinnati Reds ballgames with his buddies. He is a regular for lunch at Dixon’s Market in Corbin, a location owner Randy Dixon described as “out in the middle of nowhere” and next door to his furniture store.

Jones’s schedule is very fixed and small-town Corbin. He has lunch at Dixon’s six days a week and Cracker Barrel on Thursdays. The Dixon’s regulars joked he either comes in at 11:58 a.m. or 12:06 p.m., but he is always there, along with at least a dozen other locals. Jones will spend his 101st birthday, as he has for so many recent years, celebrating Halloween in New Orleans with Dixon.

“We spend about four days in the French Quarter watching that bunch of idiots,” he said.

Jones' Fall Honor Flight to Washington DC

On Sept 5 Jones will be part of an Honor Flight in which veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam will fly at no charge from Louisville to Washington to see their memorials. Jeff Thoke, a volunteer with Honor Flight, said of the 16 million Americans who fought in World War II only about 150,000 are left.

“How many of those,’ he asked, “trained with Ted Williams and flew off aircraft carriers?”

This past week, as a guest of Louisville Slugger, Jones was in the museum and factory, standing in the bat vault, holding a Ted Williams model bat in his hands. The full Slugger experience included a tour for Jones and three Dixon’s buddies of the Main Street bat factory. It’s a humming, tourist-laden almost vibrating place that still turns out about two million wooden bats a year for all levels of professional and amateur leagues as well as souvenir, personalized and mini-bats. About 30% of all major league players and 70% of minor league players still swing a Louisville Slugger.

The bat vault is at the center of that. It’s home to about 3,000 bats stacked in tall rows, only knobby ends and model numbers on display. These are the models used when players order their specific bats, once lathed by hand, now with computer. Their names are baseball history - Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente, Ken Griffey Jr., Derek Jeter and Ted Williams.

It was said of Williams his hands were so strong, his sense of touch so exceptional, he could tell if a bat handle was a few hundredths of an inch too thick, a bat’s weight a half-ounce off what he wanted.

Holding a Ted Williams W176 model baseball bat

Now here was Paul Jones, still second-base trim, fun and lively at 100-years-old, holding a Ted Williams W176 model in gloved hands – the gloves required to protect the weathered wood. He held the bat, as all baseball players automatically do, about waist high, hands close together, head slightly bent while examining the label, getting the feel of the bat, its weight, replaying that moment several times before stepping into the batter’s box, wiggling the bat, getting set, swing to follow.

A little later he was reading the yellow, museum-preserved cards listing all the bats Ted Williams had ordered. Then he was given a labeled “Genuine Paul Jones Louisville Slugger“ bat, the perfect gift to take home to Corbin to show all his buddies at Dixon’s.

Bob Hill was a Louisville Times and Courier Journal feature writer and columnist for 33 years.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: How a 100-year-old Kentucky veteran's baseball hero taught him to fly