Bob Hill: 'Monarchs are in peril' Why I added a butterfly waystation to our back field

All the Monarch butterfly actors and props were on the stage: A grassy meadow, red, yellow and blue pollinator flowers, ample milkweed and a soft, Southern Indiana evening. Some 82 lightly caged Monarchs were ready to test their orange and black wings and fly free. A supporting cast of about 20 neighbors, friends and especially kids were assembled. What could be more fun than watching little kids and butterflies except maybe watching big kids and butterflies?

But the thing about Monarch butterflies is that upon that very first flight they never quite look like they know where they’re going. With one of them paused on the edge of a clean mesh cage ready to give it a try.

Monarch Butterflies: the most miraculous migration in the natural world

They launch upward, zig, zag, testing fragile wings, making jagged turns in the sky, as if searching for some help with directions. But the remarkable truth is they do know exactly where they are going. Each is part of the most miraculous migration in the natural world. It’s a somewhat pass-the-baton-of-life journey that annually covers thousands of miles from Mexico to Canada and back to Mexico, pausing for a while in Kentucky and a Southern Indiana milkweed patch.

These tiny creatures the weight of a paper clip and flying on four-inch wings, have been making this round-trip for many thousands of years. Their ancestors have made similar journeys for millions of years. Monarchs can travel 50 to 100 miles a day on those tiny wings, the longest recorded journey is 265 miles. They can ride thermal winds thousands of feet in the air and then land in your back yard seeking milkweed and pollinator plants for nectar.

Humans need to take a larger role in that. The Monarch journey now is very much in peril. The use of pesticides, our obvious global warming and the lack of milkweed on which Monarchs caterpillars feed has threatened the survival of these world travelers.

Which takes us back to the Monarch butterfly poised for its maiden voyage on the edge of its cage. It was helped there by Susan Loya, who along with her sister, Barb Brewster, raised and released almost 1,500 Monarch butterflies last year. With such help Monarch survival rate is well over 90%. It’s estimated only two to ten percent of Monarchs survive in the wild, the rest killed by bug, birds, wasps, lizards, mice, parasites and toads.

Those statistics are best understood with a closer look at the Monarch life cycles. Their story begins in the protected mountains of Central Mexico where the Monarchs overwinter by the millions – and in ever-decreasing numbers - in Oyamel fir trees at about 10,000 feet altitude. They cling to individual trees by the thousands, their numbers measured in acres.

Come the warmer weather survivors head north to find mates and milkweed plants on which to lay eggs. A female can lay hundreds of eggs in her brief lifetime, but only one to three at a time on the undersides of those milkweed leaves, a predator meal waiting to happen.

The first northward “flutter” of monarchs only live about five-to-six weeks. Their life’s role is to mate. Then die. The next generation of monarchs keeps flying north, often arriving in the Louisville area about mid-May where they mate, lay eggs … and die. One or two more northbound generations mate and die before their offspring settle in or near Canada.

The Monarch Miracle grows from there. Come September or October this next “Super” Monarch generation is somehow programmed to fly all the way back to the Mexico mountains, some 2,500 miles in a journey that lasts about two very difficult months

How could Monarch butterflies possibly navigate that trip?

One recent best guess is by using tiny sensors in the adult Monarch’s antenna to detect the earth’s magnetic fields. We have to use GPS. The better guess is butterflies can read the sun’s ever-changing rays like a compass to navigate that thousands of miles over separate generations and somehow get back to that small patch of trees and mountains in Mexico they have never seen.

Beyond that this Super Monarch generation will somehow delay its reproduction cycle and now live six to eight months, long enough to survive the winter thickly layered in those trees, then head back north in spring to mate, restart the generations and die. There is also a western migration of monarchs from the Pacific Northwest and Western Rockies that winter over on the California Coast.

Susan Loya began bringing her mesh Monarch cages to our back field several years ago. A Jeffersonville native and naturalist, she remembers hiking Bernheim Forest with her Mom and wandering her yard at home looking for praying mantis, cecropia and Luna moth cocoons.

Four years ago a friend mentioned she was raising monarchs. Loya leaned in and never leaned back.

“I remember seeing my first chrysalis with those beautiful gold dots,” she said, “and when it turned transparent and I watched my first monarch butterfly emerge I was hooked.”

Which takes us a little further down the path to the miraculous inner workings of Monarch butterfly creation. We already know about the tiny eggs. They hatch into caterpillars with distinctive yellow, black and white bands and antenna to help them find and eat milkweed. That milkweed contains a toxic milk that doesn’t kill the caterpillars but does give them a lousy taste which can keep some predators away.

The voracious caterpillars, Loya calls them “eating machines,” first devour their egg shells, keep eating and growing and soon get too big for their britches. They shed their skin three or four times as they grow, then seek a place to hang in a “J” shape as they morph into a chrysalis. Ten to 14 days later —the chrysalis turning transparent in the process — a Monarch butterfly emerges; it’s body incomplete, its wings small and crumpled. The Monarch grows, pumps fluid into its wings, expanding and testing them. In a few hours it is ready to fly — perhaps perched on the edge of a mesh cage.

It was this metamorphosis process, and her sister’s interest, which got Barb Brewster interested in Monarch butterflies. She soon started a pollinator garden at her Jeffersonville home, created a registered Monarch Waystation and became active giving talks as a Master Gardener.

“Every time I search for and find caterpillars, it’s like a treasure hunt,” she said. “I know it’s a lot of work but just watching the growth and transformation of these amazing creatures and the look on the face of a child or adult when you place a caterpillar or butterfly in their hand makes it all worthwhile.”

And there is work. And a right way of doing it. Susan Loya purchased a 15 by 20-foot geodesic dome covered with transparent agriculture netting and set it up in our field. It’s planted in milkweed and colorful pollinator flowers to give mating monarchs and eggs protection, then food. But the dome is mostly used to harvest eggs.

She visited her Monarch flutter almost daily, sometimes twice a day, checking on eggs, caterpillars and pollinator plants where adult Monarchs find nectar. She’s also planted hundreds of milkweed plants in runways outside the dome where Monarchs can lay more eggs. She will give a Monarch talk later this year at Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest.

The sisters continually hunt for eggs in the field and at home. They very carefully babysit them in glass containers until the caterpillars appear. They are transferred to the clean mesh cages through the chrysalis stage and fed milkweed until butterflies are ready to fly. The cages mostly are left outside to mimic the weather and prevent disease. That whole growth process takes about 30 days.

Should Monarchs be left to make their own way in the wild?

There are critics of the process, people who believe Monarchs should be left to make their own way in the wild, that raising them artificially increases disease issues, goes against the law of survival of the fittest. They argue there is not enough milkweed left to feed the extra monarchs. The best answer to that is to grow more milkweed.

That can lead to a day when about 20 friends, neighbors and children of all ages gather in a field near a big milkweed patch to witness the release of 82 Monarchs.

It was carefully done. As the mesh cages were unzipped the most eager Monarchs flew off to freedom, not looking back. The two sisters reached into the cages, lightly picking up the butterflies by folded wings, the males easily identified by black spots on their wings.

The onlookers held back for a while, then pressed in, the Monarchs gently placed on their open hands. Most were off in a few seconds, up, up and away, including the one poised on the edge. Some linger longer, in the cages or on curious humans. The most fun was when the children press in, the monarchs resting on their hands flitting up on their arms, even their faces. The kids laugh and giggle, their parents taking pictures.

Some see spiritual blessings in monarch landings on children’s fingers. Others say the monarchs just like human sweat or are just seeking nectar in all the wrong places. The one certainty is all involved will remember the experience, the joy of lifting one arm, holding a hand open and watching a tiny, winged creature lift into the sky on its long long journey. Someday, those gathered there might even plant some milkweed.

Full details on the good lives and hard times of monarch butterflies are available at monarchwatch.org.

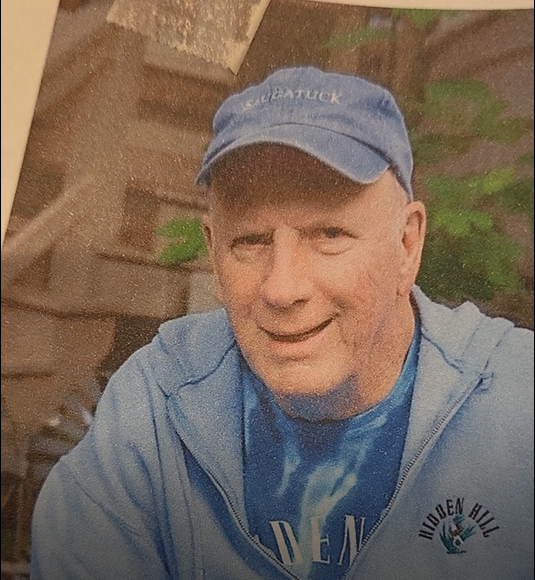

Bob Hill was a Louisville Times and Courier Journal feature writer and columnist for 33 years.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: A Monarch butterfly waystation in our yard helps their long migration