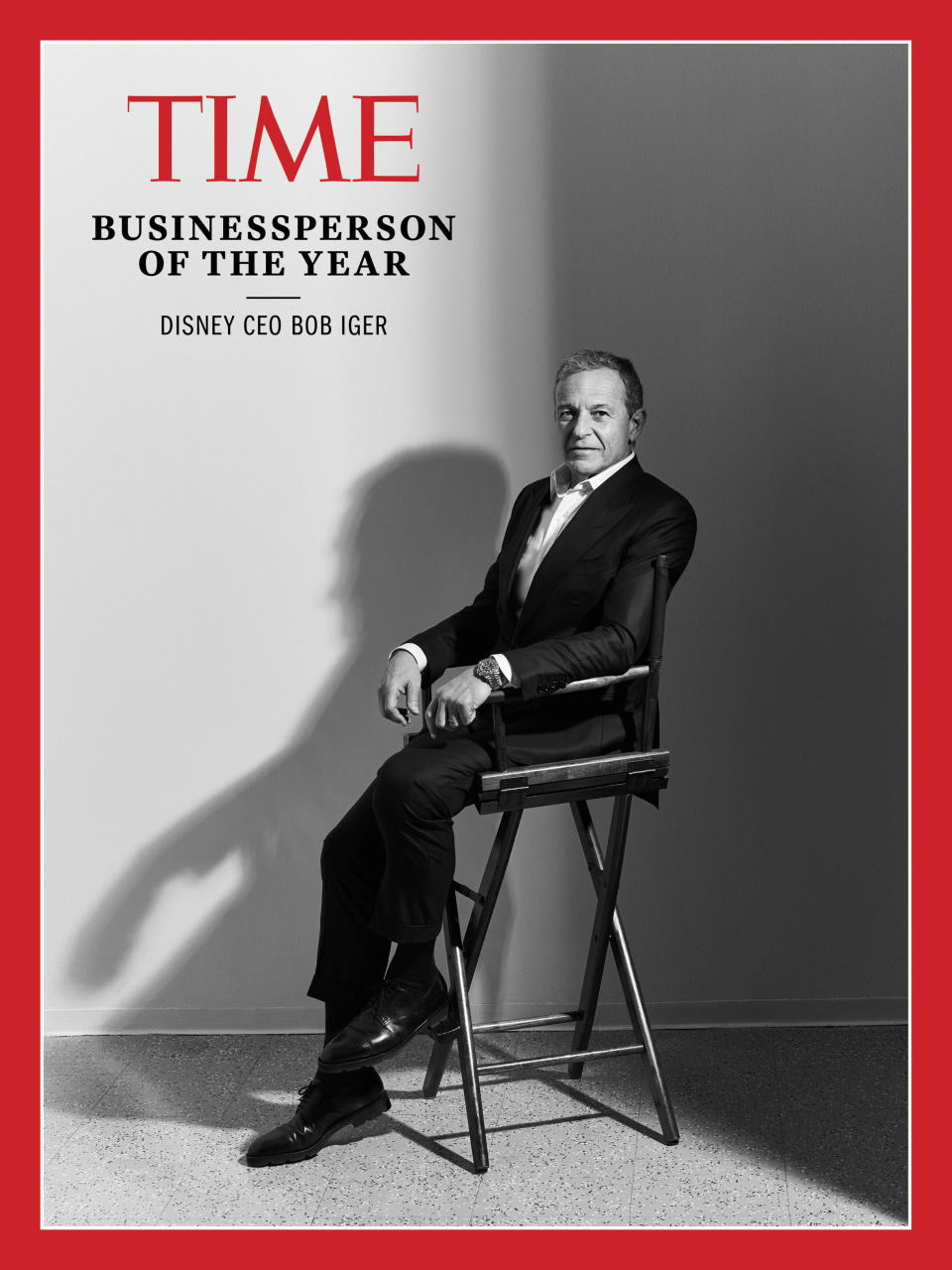

Bob Iger Is TIME's 2019 Businessperson of the Year

Not since somebody figured out that you could attach two black plastic disks to a skull cap and make everyone look like Mickey Mouse has a pair of ears sent such a buzz through a media executive. The new set were green, wing-shaped and attached to a baby space alien. The instant Disney CEO Bob Iger saw them, his heart leapt.

“As soon as those ears popped up from under the blanket, and the eyes, I knew,” says Iger, recalling when he first saw footage of Disney’s newest bankable piece of intellectual property, known to the world as Baby Yoda. He likens the feeling to when he was running ABC’s prime-time TV division and 16-year-old Leonardo DiCaprio showed up on Growing Pains. The next moves were obvious: start production on little green dolls and theme-park rides and lunch boxes, then throw open the vaults and clear space for more cash.

But Iger is the kind of guy who, if given the marshmallow test, would not only decline to eat the marshmallow, but persuade everyone else to sell him theirs and corner the market on S’mores. So he made a different call: no Baby Yoda merch yet. The cuddly alien was the heart of the new Star Wars–themed series The Mandalorian. That show was the anchor of Disney’s new streaming service Disney+, and Iger would not spoil the first episode’s big reveal.

As history will show, the auricles delivered. Disney+ signed up 10 million people by the day after its Nov. 12 launch. It is not yet a threat to the big tech companies that dominate the stream: Netflix has 158.3 million subscribers, Amazon Prime has 101 million, and Google’s YouTube has about 2 billion users a month. But if streaming is the future of entertainment, Disney—the ultimate legacy player—now has a credible vessel in which to get there.

Iger’s tenure as the leader of the world’s most lucrative dream factory has been one long CEO highlight reel. But 2019 was an apex year, when many of his carefully incubated eggs hatched. Creativity is a messy affair, technology is an expensive, glitchy one, and business plans, like military campaigns, rarely survive the first battle. Yet in 2019, Iger managed to blend all three into one epic, deal-packed 12 months. And in a year when the tide has shifted against Big Business, Big Media and Big Tech, Iger has transformed his enormous media company into a gargantuan media and tech business while ensuring that the Walt Disney Co.’s products remain widely beloved. As other corporate chiefs face steepening criticism, the worst thing he’s accused of is being a promising presidential candidate. He has rebuffed the idea. Why bother? In the post-information age, mythmakers carry more weight than lawmakers. In many ways, Iger is the Western culture’s Secretary of Stories, with the power to choose what narratives are given the most resources.

“I think the Disney+ launch has been amazing,” says Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, who was on the company’s board from 2010 to 2018. “It’s a big risk, but Bob’s really good at understanding the landscape further out as well as executing a strategy. It’s rare to be able to do both.”

***

“This has been probably one of the most productive years we’ve had as a company in the 15 years that I’ve been in this job,” says Iger, 68, who lives in L.A., but is in his native New York to host an East Coast board meeting. “This time last year, we had not closed the deal for Fox,” he says, referring to the $71 billion acquisition of most of Rupert Murdoch’s entertainment assets. “We had not opened up two Star Wars Lands, we had not launched Disney+. We had not closed the deal for control of Hulu.” Iger was also not yet a best-selling author. His seven-figure earnings from his memoir, The Ride of a Lifetime, are going toward journalism scholarships.

Iger managed all those moving parts while still making moving pictures. Even before Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker arrives, Walt Disney Studios has already released six of the eight most lucrative movies of 2019, and broken the $10 billion global box office barrier. Avengers: Endgame is now the highest-grossing movie of all time, selling $2.8 billion worth of tickets globally since it was released in April. Investors are thrilled; the stock is up 34% this year.

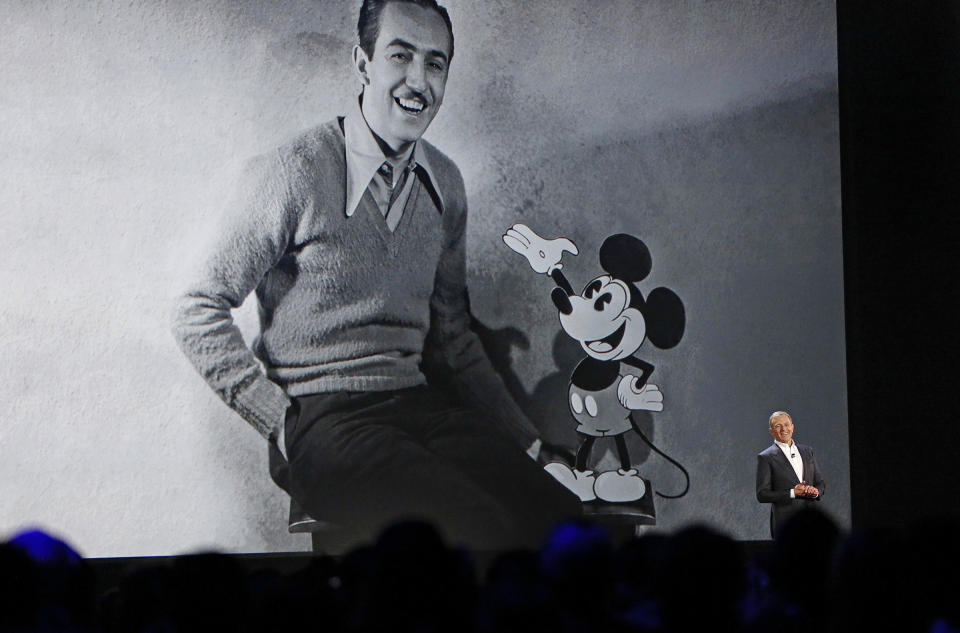

The entertainment business isn’t just about money, though. When Disney generates a successful franchise, the characters and myths it creates occupy the culture to a degree that they can amplify or dampen people’s understanding of who they are and what they stand for. Movies like Black Panther and Frozen take up so much of the national attention span that the communities and identities those films portray become less other, more central.

Of course, not everyone celebrates Iger’s choices. Many bemoan Disney’s blanding effect on the culture—including director Martin Scorsese, who in November wrote in an excoriating New York Times op-ed that movies from Disney’s Marvel studio lacked “revelation, mystery or genuine emotional danger.” He claimed that the focus on franchises—a key Iger strategy—was contributing to a situation that “was brutal and inhospitable to art.”

Iger, famous for his Mandalorian-like imperturbability, calls Scorsese’s comments “nasty” and “not fair to the people who are making the movies,” but brushes them off. “If Marty Scorsese wants to be in the business of taking artistic risk, all power to him,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that what we’re doing isn’t art.” In true Hollywood fashion, Iger says his people and Marty’s people are arranging a get-together.

Whenever he’s accused of taking no risks, Iger points to Black Panther, which he considers one of his top five career achievements. “I expected Bob’s [advice] to be more conservative, but it was actually the opposite,” says Panther director Ryan Coogler. “He wanted us to be more aggressive and ambitious.” Iger encouraged him to build out the theme of transgenerational trauma as it relates to race. “He wasn’t afraid from a cultural standpoint or a business standpoint.”

Nearly every story about Iger’s tenure at Disney contains a variant of the sentence This is his biggest gamble yet. In 2006, he made a $7.4 billion deal to buy Pixar from a guy who hated Disney. Then he bought Marvel, a company built on the mercurial fantasies of adolescent males, then Lucasfilm, when the Star Wars stories seemed burned out. And this March, he persuaded the mulish Murdoch to sell him nearly all his marshmallows too.

Disney+, however, makes those other bets look penny-ante. Iger had slowly and somewhat stealthily bought BAMTech, the company Major League Baseball used to stream games, which provided the technological back end. But he knew the only way to bring people to a new streaming service is with shows they can’t miss. “There was a meeting. In the Disney boardroom,” says Iger, whose way of telling stories is as consistent and methodical as his schedule. Heads of the company’s creative shops were told to come with pitches for the new service. “I said, ‘We’re not creating another separate studio. You will all be the suppliers. No. 1 priority.’”

Of all the suggestions he heard that day, it soon emerged that only The Mandalorian would make it in time. It—and by extension Baby Yoda—would have to carry the whole launch. Iger was right to keep that black-eyed sweet pea a secret, because the culture wasn’t going to wait until gift season. The Internet was swiftly flooded with Baby Yoda–bilia, including knitted hats, baby items, love songs, DIY Christmas ornaments and, of course, memes. So many memes. Iger sent friends his favorite, a mash-up of cosmological narratives featuring the Pope holding Baby Yoda like a communion wafer.

***

In some circles, Iger is considered only marginally less alien than the creature he greenlighted. He has worked for the same company for 45 years, through 20 jobs and 14 bosses, outlasting scores of rivals, apparently without making any major enemies. “You will never hear, ‘Bob Iger, he’s such a son of a bitch,’” Gayle King—not even on his payroll!—said last year. When he finally got a shot at the top spot, however, there were doubts; the interview process was so long and humiliating he ended up at the doctor’s office with an anxiety attack. The $65.6 million he earned last year seems to have eased but not erased the memory.

Of course, Iger may have bet wrong. Disney has already spent $3 billion on the service and plans to spend billions more on a venture that may never turn a cent. The Star Wars and Avengers narratives are reaching their outer atmospheres. Hong Kong Disneyland is almost empty amid the ongoing protests. And he has still not named a successor.

But for now, for just this moment, Iger is unassailable. He’s transformed his company from a stuffy media doyen into a sexy cultural force. He can glide to retirement in 2021 on the fumes of that triumph. Except it’s not his style. When asked which IP he would buy if in some fantasy world he could: Harry Potter, Gandalf or James Bond, Iger smiles. “We’re not looking to buy anything right now,” he says. “But I’ve always been a huge James Bond fan.”