A bobcat could live in your neighborhood | ECOVIEWS

![An adult bobcat on the prowl at night stops to look for prey in a hollow tree. [Photo courtesy Whit Gibbons]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/9KblQDr7oVa5ouHyj0ufSw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD0xNDAz/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-tuscaloosa-news/2eb04475185294c9fd24746caf295c6c)

Someone showed me a wildlife camera photograph of a bobcat walking across their backyard in a suburban area.

The bobcat’s ability to adapt in the wilds throughout North America has been validated by their ubiquity on a continental scale. Their geographic range includes southern Canada to Mexico and every one of the lower 48 states. Their adaptability around human habitations confirms their aptitude for making the best of a situation.

Like others in the cat family (Felidae), bobcats are totally carnivorous. Eating other animals is imperative. Any bobcat strolling around a suburban neighborhood is eating rabbits, squirrels, rats, birds and cats. None of them would stand a chance against such a powerful predator.

MORE FROM ECOVIEWS: What can happen in a cypress swamp?

One reason that bobcats seem secretive from a human perspective is because they prowl mostly after dark in areas where people are unlikely to be present. However, on occasion they will also hunt during daytime hours. Bobcats have yellow eyes with black pupils, and I know from experience they can be captivating, for I have stared into the eyes of wild bobcats three times.

My first encounter was when I found a pair of bobcat kittens in a hollow log. They looked at me the way any tiny kitten would. Unimpressed but with a hint of curiosity.

My second eyeball-to-eyeball encounter was during a field trip on the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site. I was showing ecological research sites to a visiting graduate student, Art Benke, who would later become a biology professor at the University of Alabama.

As we traveled in a remote area, a mother bobcat followed by two kittens the size of small housecats ran across a gravel road. We jumped from the truck to get a better look at them in a grassy area before they reached the nearby woods. To my surprise, the baby bobcats stopped where they were and lay on the ground, the way a scared fawn does. I walked over to the two brown furry balls with dark spots. Both looked up with innocent, imploring yellow eyes.

My inclination was to reach down and pick one up. They were that cute. Fortunately, reason overruled impulse. Reinforcement about making such a foolish move came when I realized that the momma bobcat had stopped and was standing only 15 feet away. She was looking at me intently. Her eyes sent a chilling message.

Quick calculation: picking up a baby bobcat with a protective mother a few feet away would be absolutely absurd. Art and I watched a bit longer and then waved them goodbye as we drove off.

My oddest experience in a stare-down with a bobcat came with one captured in a live trap. The not-too-happy feline was not injured, but as I approached, it snarled and slammed a paw with extended claws toward me. Again, something drew me to its yellow eyes, which stared vehemently at me, trying to stare me down in a true visual confrontation.

Our eyes remained locked for several seconds, and the cat would have won the staring contest had I not had the safeguard of steel mesh between us. Then a remarkable thing happened. Its pupils dilated fully, transforming abruptly into a pair of solid black eyes. I started and jerked my head back but held my gaze. Then it looked away, lowered its head and retreated to the other end of the trap. It seemed docile as a kitten.

As I opened the trap, it sprang toward the woods and never looked back. It was a hollow victory in which the real pro had lost only because I had taken an undeserved sports handicap.

Knowing that top tier predators like bobcats persist — despite the myriad threats inflicted on all wildlife by human activities — is gratifying to anyone who enjoys having a touch of the wild left in the neighborhood. Let’s hope everyone will eventually get to see one close up, but not so close as to stare into its eyes.

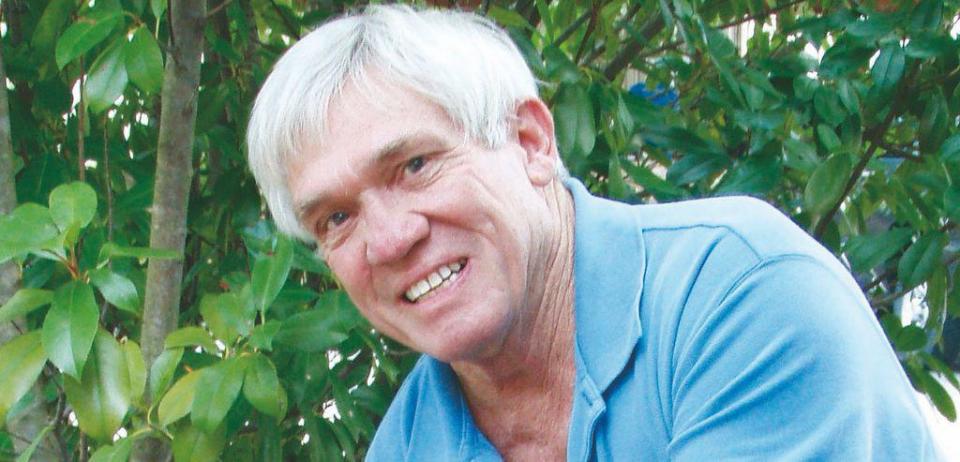

Whit Gibbons is professor of zoology and senior biologist at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory. If you have an environmental question or comment, email ecoviews@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: A bobcat could live in your neighborhood | ECOVIEWS