Bodies on the streets and presidents in denial: how Latin America is emerging as a new virus epicentre

Bodies pile up in the city of Manaus, northern Brazil, as the town is brought to its knees by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The local health system collapsed over two weeks ago, while gravediggers resorted to burying the dead in mass graves known as "trenches."

A shortage of gravediggers forced one family to bury their father themselves, after spending three days searching for his body among the heaps of corpses.

"There were lots of bodies on top of each other, without any identification", said one man, speaking to the local press.

Brazil is fast becoming the new epicentre of the Covid-19 crisis in Latin America, with the daily death toll now beginning to outstrip some of the worst affected countries in Europe.

Ecuador dominated the headlines in April, where the disease has spread uncontrolled and bodies have been left to rot in the streets, and many fear Brazil is on a similar path.

Leadership in Latin America will determine the fate of millions. As some nations take a laissez-faire approach to preventing the virus, others are introducing draconian lockdowns. The virus is impacting everyone – from prison inmates and gang members to migrants on the move.

Brazil

Brazil’s far-Right president Jair Bolsonaro remains dismissive of the public health emergency. In a press briefing last week, when asked about the 474 deaths registered in Brazil that day, Mr Bolsonaro replied: "So what?"

"I'm sorry. What do you want me to do?" he added.

Mr Bolsonaro has repeatedly played down the severity of Brazil's Covid-19 epidemic, repeatedly referring to the disease as a "little flu" or "the sniffles".

Brazil's neighbours are worried they could catch the same contagion levels as Brazil. The giant South American nation, which shares its large, currently open border with every other country in South America bar Chile and Ecuador, has recorded between 400 and 500 new deaths every day this week, putting it on par with daily increases in European countries.

As of Sunday, the total number of cases was 101,147, with a death toll of 7,025.

Infectious disease experts say a lack of testing and delays in diagnoses has led to gross under-reporting in Brazil's Covid-19 data. Brazil's official numbers could be only 10 per cent of the actual total of Covid-19 cases, according to a recent study from the Imperial College of London, meaning that 1 million citizens could be infected.

The possibility of under-reporting has even been acknowledged by Brazil's health minister, Nelson Teich, who said last week that the country is "flying blind" in the pandemic.

El Salvador

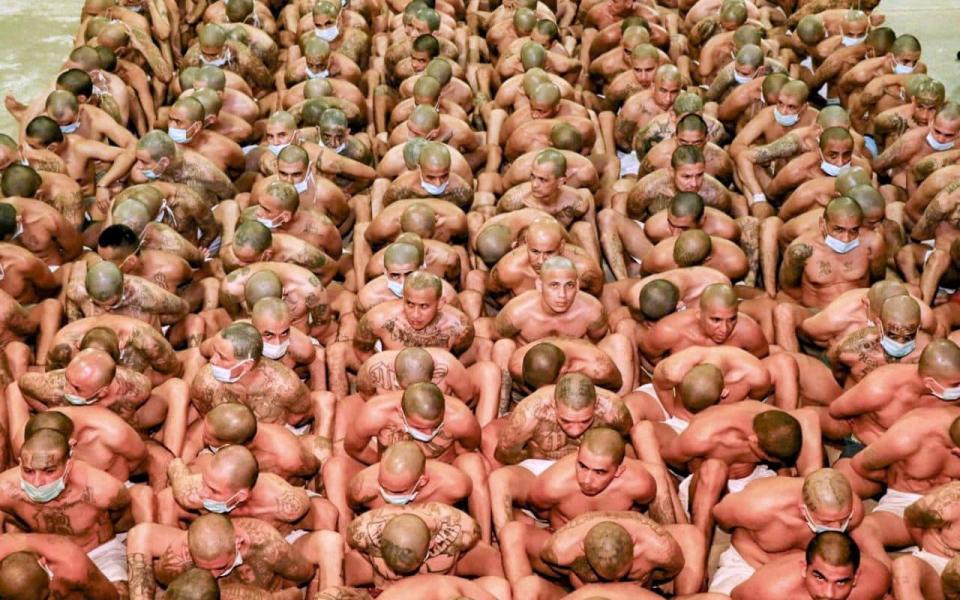

Pictures from the prisons of El Salvador showing hundreds of shirtless, tattooed members of the country’s notorious “Mara” street gangs sitting on the floor in one of the country’s penitentiaries have been shared widely.

While they are touching chest-to-back, some of the men are also, curiously, wearing face masks over their noses and mouths.

With governments worldwide stressing the importance of no physical contact between individuals, the El Salvadoran jails are being held up as an example of a social-distancing calamity.

Nayib Bukele, El Salvador's president, has courted controversy. He introduced a strict nationwide lockdown on the streets of the central American nation on March 23, but inmates are still forced together.

Outside prison walls, Mr Bukele issued orders for security forces to “get harsher with people in the street” if quarantine measures are not obeyed.

However, gang-related murders soared during the lockdown, infuriating Mr Bukele, who accused the gang members inside prison of orchestrating the homicides, claiming they were taking advantage of the fact that police and armed forces had their attention on the coronavirus measures.

The president authorised security forces to use “lethal force” against suspected gang members on the streets. In the prisons, he pushed inmates from rival gangs together as a punishment.

Historically, members of the rival gangs – Marasalvatrucha and Barrio 18 – have been kept apart in different prisons wings or entirely different penitentiaries.

Mr Bukele’s lockdown measures have attracted a good deal of criticism from human rights groups, but the unfettered spread of the virus does seem to have been halted, while it has created other security issues. El Salvador was one of the first countries in the region to introduce a lockdown, and to date has reported 490 cases and just 11 deaths.

Peru

After Brazil, Peru is reporting the largest number of cases in the region, with some 45,928 reported by Sunday, but just over 1,286 deaths – a much lower death rate than neighbouring Brazil’s.

Unlike its beleaguered neighbour, the country announced a national emergency in mid-March that was strictly enforced, and included a nationwide curfew from 8pm to 5am, closing its borders with Brazil as well as Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia, and prohibiting domestic travel.

And unlike Mr Bolsonaro in Brazil, President Martín Vizcarra enjoyed overwhelming support for his reaction to the pandemic - an Ipsos poll released March 22 found that his approval rating jumped 35 points in one week to 87 per cent. Ninety six per cent of people approve of the curfew, and 95 per cent support the countrywide lockdown.

However, pockets of panic have broken out around the country, including in some of its penitentiaries. Inmates in a jail in the capital Lima rioted after men in the jail died of Covid-19, fearing a major outbreak among the prison population.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet - Chile's former president - warned countries not to forget those behind bars during the epidemic, prompting Mr Vizcarra to give 3,000 of the most vulnerable prisoners a humanitarian pardon to ease prison overcrowding.

Chile

Chile ordered strict new quarantine measures on three districts in the capital Santiago after a sudden spike in coronavirus cases Sunday.

The health ministry reported a surge of 1,228 new infections, bringing the total to nearly 20,000 nationwide and dealing a blow to hopes it was over the worst of the crisis.

The setback follows criticism of the reopening of some commercial streets in Santiago after the government last week outlined "a return plan" for the economy.

"If we do not win the battle in Santiago, we can lose the war against the coronavirus," warned Health Minister Jaime Manalich.

Cerillos, Quilicura and Recoleta districts - as well as the northern mining city of Antofagasta - would be quarantined from next Tuesday, he said.

Santiago, with a population of seven million, has been the country's main center of infections, particularly in its three richest suburbs.

However, the virus began to spread in the city's more densely populated areas over the past couple of weeks.

The setback follows criticism of the reopening of some commercial streets in Santiago after the government last week outlined "a return plan" for the economy.

Ecuador

Some of the most harrowing scenes from the pandemic have played out in Ecuador. Families felt forced to dump their dead on the street in the hope that they would eventually be collected, and coffins piled up by the hundreds in saturated morgues, according to reports. Corpses slumped in wheelchairs and on the floor in emergency areas of some hospitals.

The government has reported 29,538 cases and 1,564 deaths, but President Lenin Moreno has said that the official number is “coming up short” and has called for transparency.

An analysis by the New York Times suggests that the tiny nation could be experiencing one of the most devastating rates of the coronavirus in the world.

Despite the continued spread and lockdown measures, local media reports more cars and pedestrians have been spotted in Guayaquil’s streets in recent days.

At the end of April, coronavirus-related deaths began to drop and the government planned to loosen the lockdown.

“We can say that the peak has already passed in most provinces,” Maria Paula Romo, the interior minister, said earlier this week.

“We will go from isolation to distancing.” She said the decision will be reversed if infections pick up again.

Venezuela

Venezuela Carmen Bodega recently started walking towards Venezuela from the Colombian city of Bogotá with her two-year-old daughter, Chrislady Hernandez. A migrant, she came from Venezuela’s Aragua state to Colombia two years ago. A domestic cleaner, she hasn’t been able to work since coronavirus lockdown measures were introduced.

“Where we were living, if we didn’t pay our rent when the quarantine ends, they were going to kick us out,” she told The Telegraph. “Nobody was helping us with food or anything and they required us to be cooped up all day. The owner told us he would be evicting us.”

After fleeing to neighbouring Colombia in high numbers for the last few years, 12,000 Venezuelans have recently returned to their Venezuela due to Colombia's strict lockdown measures. The migrants, mostly informal labourers, say they’ve lost their income and homes in Colombia.

The numbers so far represent a small portion of the 1.8 million Venezuelans who have fled in recent years due to the ongoing economic and humanitarian crisis in their country.

While some Venezuelans have travelled to the border in buses, dozens can be seen walking on the highway leaving the Colombian city of Bogota daily. The walk is a two-week journey of over 500 miles that takes travellers across a mountain range where temperatures drop below zero.

Nicolás Maduro, the Venezuelan president, has promised to welcome the migrants back home “with love,” but opposition lawmakers in Venezuela said migrants have been forced into public buildings for a 14-day quarantine, at times without running water and little food.

Videos shown to The Telegraph show migrants complaining they’re sleeping on the floor as “Maduro claims we’re in luxurious hotels.” Another migrant claims that one person who tried to leave the school grounds was beaten by guards.

Venezuela, which has a population of 30 million and a government considered opaque at best, has reported 357 cases of coronavirus and 16 deaths.

Mexico

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the Mexican president, was slow to bring Mexico to a standstill, and lockdown measures are being respected to varying degrees around the country. Compliance is based largely on social class.

With more than half of the labour force in the informal sector, millions live hand to mouth and feel that they cannot afford to stop working, regardless of the health risks.

Mr Lopez Obrador, a Leftist, has shied away from the kind of draconian lockdowns being enforced by the likes of Mr Bukele in El Salvador. Many believe he fears being perceived as using repressive measures, and he has made extremely optimistic statements about Mexico’s capacity to fight the virus.

In late April he said that Mexico “was able to tame the coronavirus pandemic because the population complied, to the letter with the health measures laid down by the government, thus ensuring that there is no outbreak of infection and hospitals are not overcrowded”.

With 2,154 deaths and 23,471 cases, Mexico is in Phase 3 of its pandemic and reports of struggling hospitals and a health system overwhelmed are all over the national media. Despite evidence to the contrary, Mr Lopez Obrador has stated that he expects the lockdown to be lifted by the end of May.