Boesen said she didn't know one of the men behind attack fliers. Her campaign manager did

Josh Mandelbaum says it was fellow Des Moines City Council member Connie Boesen who first nudged him over a year ago to lunch with Republican power broker Doug Gross.

Mandelbaum had just tried and failed to float a resolution on the Des Moines City Council to try to safeguard abortion access for city residents, and he said he knew he and Gross were miles apart on key issues. But Boesen told him Gross was hunting for a candidate to challenge Mayor Frank Cownie.

Mandelbaum recalls Gross telling him that day at Tupelo Honey downtown that he was too liberal to win his support for the mayor’s race. Back then, Cownie had not yet announced his retirement and Boesen had yet to decide that she, too, wanted the job.

On Nov. 7, Boesen bested Mandelbaum in the squeaky-tight race. And Mandelbaum ― knowing now how far Gross would go to defeat him ― regrets even trying to break bread.

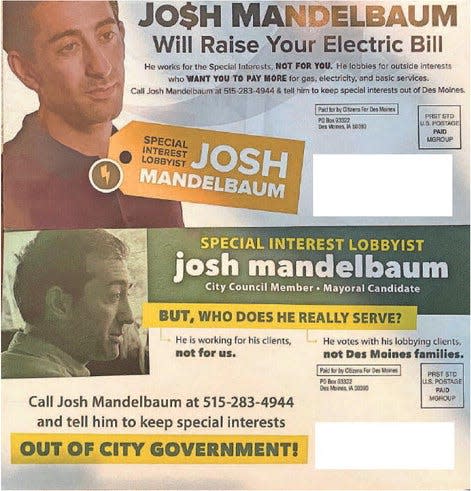

Mandelbaum said he knew Gross had thrown a lucrative fundraiser for Boesen at his firm, BrownWinick, and was a major donor to her campaign. But in late October, Gross and two others went a step further, forming a nonprofit, Citizens for Des Moines, that paid to blanket Des Moines voters with fliers aimed at tainting Mandelbaum’s record in the final days before the election.

“It was a dirty tactic,” Mandelbaum said of the fliers. “What they put out there was untrue, false and deceptive with no time for me to effectively respond.”

Gross did not return Watchdog's phone calls seeking comment.

The fliers triggered Bleeding Heartland’s Laura Belin and the Des Moines Register’s opinion editor to fire off 11th-hour pieces just before the election, decrying the tactics. On social media, commenters called scurrilous the fliers' claims that Mandelbaum might try to ban gas stoves or gas-powered cars. Some on Reddit tried to figure out why Citizens for Des Moines didn’t have to file any disclosure forms and questioned whether Boesen was a closet Republican.

Boesen, who won by 48.2% to Mandelbaum's 45.8%, told Watchdog she didn’t need Citizens for Des Moines’ support, didn’t like its tactics and didn’t endorse it.

She said her campaign polled voters in October, and the results, which she never shared with Gross, showed her in the lead.

The fliers "served me no purpose,” she said. “If anything, they probably hurt me more than helped me.”

On paper at least, the mayor's job and those of the elected City Council members are supposed to be nonpartisan. But big donations flowed this year to both candidates in the mayor's race, where Mandelbaum appeared the more liberal candidate, supporting city action to protect abortion rights, while Boesen called for keeping the focus on local issues.

On the afternoon after the election, disdain over what some voters saw as chicanery in the mayor's race was still heavy on their minds.

When Gross and Tom Henderson, former chairman of Polk County's Democratic Party, faced a full house for an Osher Lifelong Learning Institute question-and-answer discussion at the Harkin Institute in Des Moines, Mary Riche, a supporter of Mandelbaum’s, said people pressed Gross to answer questions about the fliers and his tactics.

Gross, she said, told the crowd he did what he did because Mandelbaum was winning. “I almost fell out of my chair,” she said.

Gross said the tactics are allowed as long as the U.S. Supreme Court's 2010 decision stands in Citizens United v. FEC. That much-debated 5-4 decision held that the First Amendment’s free speech clause prohibits the government from restricting independent campaign spending by corporations, including nonprofits, labor unions and other associations.

The last bill by Iowa lawmakers calling for a constitutional convention to address the Citizens United decision failed in 2017.

While Boesen denies link to Citizens for Des Moines, her campaign manager worked previously with one of its organizers

Citizens for Des Moines’ fliers said Mandelbaum, who works and lobbies for the Environmental Law & Policy Center, "promotes policies that raise your utility bill" and “only looked out for his clients.” In the fliers, the group references a draft resolution from Mandelbaum in October 2020, approved by Boesen and other council members, that supported "achieving 100%, 24x7 electricity from carbon-free sources by 2030."

Gross, a well-known lawyer for BrownWinick and a former lobbyist, was a former chief of staff to Gov. Terry Branstad and ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2002.

We know from filings at the Iowa’s Secretary of State’s office that one of the people who helped Gross form Citizens for Des Moines is Mark Roth, another attorney at the BrownWinick firm.

Another man listed as an incorporator was Alejandro Verdin, who had only a post office box listed for an address on the nonprofit incorporation papers. Boesen said she'd never heard of him.

But the man she hired to take over her campaign in September, Sam Roecker, confirmed in a phone call Monday that he had worked with Verdin, who earlier this year was a campaign manager for the liberal Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Janet Protasiewicz. Protasiewicz was elected this spring in the most expensive Supreme Court race in U.S. history.

Roecker was her campaign spokesperson, according to a recent article in Politico. Another top aide for the justice was Ben Nuckels, whose Democratic media consulting business also worked for Boesen's campaign, according to campaign finance documents.

Verdin, reached briefly Monday afternoon, said that no one had hired him in Iowa and that he would call back later in the day, but he had not by press time.

Voters didn't get to know about those connections before the election.

Voters also didn't know that BrownWinick, Gross and Roth's law firm, also had penned court briefs defending the same 24x7 renewable energy standard on behalf of Google, a major client, that Citizens for Des Moines attacked Mandelbaum for supporting in the fliers. The firm argued in an Iowa Utility Board case involving MidAmerican Energy that the standard would save customers money, while the Citizens for Des Moines fliers claimed it would cost them more.

Here's the rub: In the post-Citizens United world in which we live, voters don’t get to know anymore everyone behind attempts to manipulate elections or how much they’re spending to change the course of a campaign.

Try as some have, efforts aimed at bringing more oversight and more transparency to dark money spending and political advocacy by the right and left have thus far failed in Iowa.

Iowa Code 68A requires organizations and individuals who spend in excess of $1,000 in order to "expressly advocate" the election or defeat of a candidate or ballot issue to file a statement within 48 hours of the independent expenditure and disclose their donors. But in forming Citizens for Des Moines as a nonprofit, and not as a campaign subject to political spending regulations, Gross and his partners bypassed the disclosure law.

Zach Goodrich, executive director and legal counsel for the Iowa Ethics and Campaign Disclosure Board, said the mayor’s race in Des Moines was just one example among many leading up to local elections about which people complained.

The Cedar Rapids Community School District, Goodrich said, used public resources to publicize a bond referendum for their facilities. People complained the district improperly used its resources for political purposes, but because the district’s actions weren’t “express advocacy,” or telling people how to vote, it was permissible under Iowa law, Goodrich said.

“We had similar complaints of other public entities persuasively promoting, but not expressly advocating, in bond referendums,” he said.

“I understand and sympathize with those who want the law changed to have more transparency from those who spend money to influence elections. That being said, I don't know where the line to require reporting to our office would be drawn for persuasive/influential materials, particularly when it comes to crafting a law that would be upheld in the courts.”

Iowa lacks enforcement in campaign finance, disclosure law

Goodrich said a bigger problem right now is that his agency also lacks power to enforce existing law.

“Even if a new law were passed, someone could violate it with no real consequence,” he said. “Iowa law has no deadline to pay the civil penalties our board issues and no consequence for not paying those penalties.”

Goodrich said many of the laws governing the agency haven't been updated since 1993, relating to basic things such as adjusting dollar amounts for penalties or reflecting that his office has switched from paper to electronic filing.

“We tried this past legislative session, but the bill had other changes tacked on that were unpopular and ultimately doomed it,” he said. “Ultimately, I'd say that changing the law to lower the bar for reporting to our agency should only come after we make other necessary and common sense updates that would let us better serve Iowa.”

Goodrich said his board is voting Thursday to finalize its 2024 legislative proposals. and he expects the same bill to come up again. “We'll also be discussing the express advocacy issue since it's been a hot-button issue lately,” he said.

But any changes there are unlikely to withstand court decisions because of free speech protections, he warned.

According to an analysis by the Center for Responsive Politics, which maintains the OpenSecrets.org website, 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations are the most frequently used entities to transfer dark money. That money can move from nonprofit to nonprofit and has a profound effect now on local elections.

For years, a mix of national advocacy organizations like Common Cause have tried to push the U.S. Internal Revenue Service to block nonprofit political committees that hide the identity of their donors.

The groups say hundreds of millions of dollars are being funneled through the 501(c)(4) social welfare groups by partisan operatives. Social welfare activities, according to the IRS, aren’t supposed to include direct or indirect participation or intervention in political campaigns.

In 2018, the Federal Election Commission issued guidance to nonprofits in response to a D.C. district court judge's ruling requiring nonprofit groups to disclose donors who give more than $200 for political purposes. However, the mandate applied only to groups making independent expenditures of more than $250, and many groups found ways to avoid disclosure.

Some advocacy organizations, like the Brennan Center for Justice, believe publicly funded elections would help counter the influence of the extremely wealthy by empowering small donors.

As of 2018, 24 municipalities and 14 states had enacted some form of public financing, and at least 124 winning congressional candidates voiced support for public financing during the 2018 midterm election cycle.

Many are pushing for more transparency in election spending on the national, state, and local level.

The DISCLOSE Act, introduced several times in Congress, aimed to strengthen disclosure and disclaimer requirements, enabling voters to know who is trying to influence their votes. That act was incorporated in 2019 into the broader For the People Act (H.R. 1), which passed the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives, but did not advance in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Some also want Congress to prevent super PACs and other outside groups from coordinating directly with campaigns and political parties and push the FEC to finally update campaign finance safeguards.

Boesen and Mandelbaum said they both support campaign finance reform, and polls suggest most Americans want to limit campaign spending. But polls also show few Americans know much about campaign finance.

If you're still irked, the best place to start is getting educated.

Lee Rood's Reader's Watchdog column helps Iowans get answers and accountability from public officials, the justice system, businesses and nonprofits. Reach her at lrood@registermedia.com, at 515-284-8549, on Twitter at @leerood or on Facebook at Facebook.com/readerswatchdog.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Dark money in Iowa local elections stirs questions, anger among voters