Bold New York developer bets $2 billion on Miami Beach, starting with Raleigh Hotel redo

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

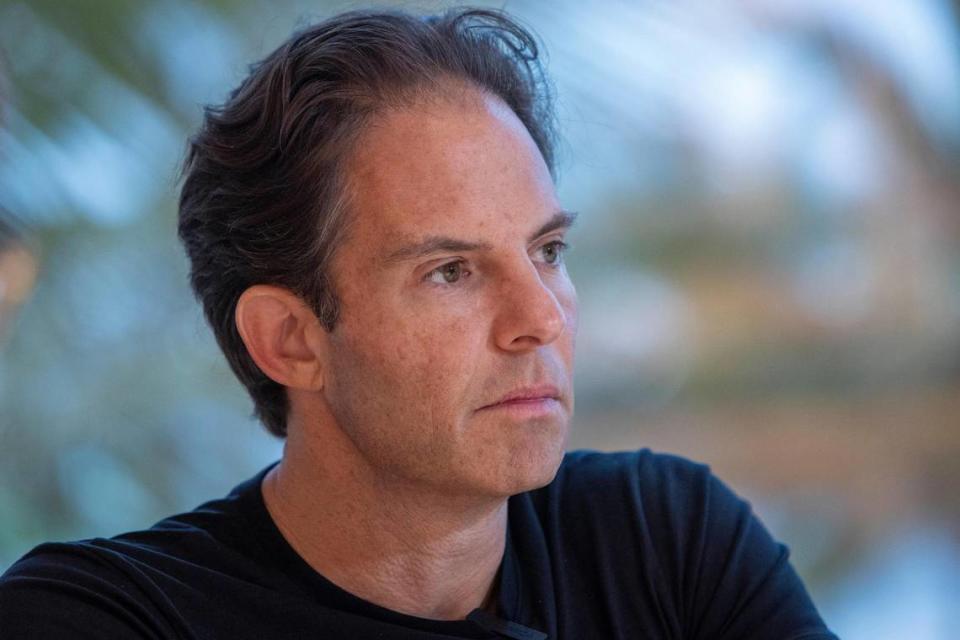

A few years ago, a brash New York real estate broker-turned-developer, whose binge-buying of trophy buildings in major U.S. cities made him an industry power player, turned his attention to relatively puny Miami Beach.

He wanted only one thing at the time: To buy and restore the 80-year-old Art Deco landmark Raleigh Hotel, sadly vacant since 2017.

That’s where the story of how Michael Shvo decided to transform the city of Miami Beach begins. And now he wants so much more.

If all goes as planned — Shvo is betting a couple billion dollars, some of it his own money, on the outcome — the tale ends a few years hence with some momentous results: Not just a lavishly renovated Raleigh, but a Miami Beach metamorphosed from resort town and part-time abode for affluent outsiders into a place where serious people for whom no luxury is too indulgent can conduct serious business in seriously high fashion.

“I want this city to be amazing,” Shvo said, outlining plans for a set of South Beach office buildings designed by star architects with hospitality appointments so rich they would make a Four Seasons blush. “We’re making Miami Beach a place where you don’t only come for the sand, you don’t only come to play, you don’t only come to eat, you don’t only come to live, you actually come to work. That work completes the city.

“The urban fabric of Miami Beach,” he immodestly vowed, “is going to change.”

Shvo, who is 50 and immigrated from Israel in his early 20s, may not be the first out-of-town developer to land in Miami Beach bearing extravagant promises. Nor is he the first with a blot on his legal record — in Shvo’s case, a guilty plea and a $3.5 million settlement with New York state prosecutors on criminal tax fraud charges in 2018.

But he comes with backing by big, conservative German financiers and pension funds, a record of high-grade new construction in historic areas coupled with scrupulous and remunerative restorations of historic and architecturally significant buildings, a relentless work ethic and — perhaps unusual for a developer — an apparent willingness to make himself available to the locals to discuss his plans and seriously consider their input.

In a city defined by its historic architecture, that has so far been enough to allay reservations from Beach officials and its leading preservation group over Shvo’s record and intentions. It has even inspired confidence that he’ll deliver on what he promises.

“When I first met him, and started going over the Raleigh and other projects, I thought he was paying attention to the desires of our community to preserve history and improve on it,” Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber said. “I judge him by his conduct with the city, and he’s been very transparent with us. I think he’s restoring some of our history, and creating new history.”

Daniel Ciraldo, executive director of the Miami Design Preservation League, said Shvo has not only put time into building constructive relationships with locals, but has also helped support preservation initiatives.

“I think of other big personalities that have come on the scene in the past years, and Michael has that level of ambition, if you look at the portfolio of landmarks he’s accumulated. It seems like he is the real deal,” Ciraldo said. “You can tell he really loves design and is really passionate about it. I don’t think mediocre is in his vocabulary.”

Doing what Tommy Hilfiger couldn’t

Now Shvo just has to pass his first big test.

He got the Raleigh in 2019, after a few rebuffed offers, for a tidy $103 million. In Shvo’s retelling, he muscled out Tommy Hilfiger, who had owned the Raleigh since 2014, after the fashion designer’s Turkish backers ran into financial trouble, halting their effort to renovate the South Beach celebrity haunt. The hotel had been forced to close by damage from Hurricane Irma.

“It needs a full redo; it’s a bit dated,” Hilfiger had said of the storied 1940 hotel when he acquired it, raising worries from Beach preservationists about his plans, though he never got a chance to finish the job.

If only Tommy had known what Shvo had in mind.

Today, four years after Shvo closed on the purchase, the Raleigh stands stripped to a shell as construction gets underway on a go-for-broke plan that calls for an architecturally rigorous $500 million restoration of the historic hotel, accompanied by a major expansion of the beachfront property.

The grand plan, drawn up by celebrated architect Peter Marino, the go-to biker-leather-clad designer of luxury multinational LVMH, and Miami’s ubiquitous Kobi Karp Architecture, aims to up the opulence quotient while bringing the Raleigh’s exterior and public spaces back to their original, streamlined late-Deco splendor, including, of course, the famous pool and legendary lobby bar.

But that’s not all.

Next door, all that remains of two smaller, and also historic, Art Deco hotels by same prominent and prolific architect of the day who designed the Raleigh, L. Murray Dixon, are the buildings’ fronts on Collins Avenue, braced by thick steel poles.

Shvo, who bought the Richmond and the South Seas hotels for $64.5 million and $52 million, respectively, managed to secure approval from the Beach’s notoriously strict historic preservation board to knock down the rear of the two-story hotels, making space behind them for a planned 175-foot-tall, ultra-luxury tower with 17 floors and 42 condos, also by Marino and Karp. That’s somewhat taller than what’s allowed by existing zoning for the area.

The facades of the two historic hotels, worn and altered over the years, will be restored and serve as the frontispieces for new standalone buildings housing a restaurant and five hotel suites. Residents, meanwhile, will enjoy full privacy with their own separate amenities, while also having the run of the entire 3-acre property, all of it to be managed by the super-deluxe Rosewood Hotels group. Sales in the hundreds of millions will help fund the hotels’ restorations.

Massive advantages to restoration

Shvo, a professed “control freak” for whom no detail is too small to endlessly obsess over, said construction will take a full three years from now, to get everything just exactly right. Buying, preserving and scrupulously restoring historic buildings while modernizing their functioning has become a distinguishing Shvo hallmark — one he said has proven to be very good business, contrary to what certain of his peers may think.

His marquee purchases comprise some very recognizable buildings: Among others, they include the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, downtown Chicago’s Big Red tower and, in New York City, the turn-of-the-century 530 Broadway in SoHo and 711 Fifth Avenue, an iconic 1927 retail and office building once home to NBC’s studios and, later, Coca-Cola. All have since received extensive renovations and upgrades that preserve their original designs, Shvo notes.

Shvo and Soviet-born billionaire developer Vladislav Doronin, meanwhile, bought and turned the top office floors of Manhattan’s 1921 Crown Building into a high-luxury Aman Hotel.

“We’re very much focused on elevating super-prime real estate” Shvo said of himself and his partners during a recent four-hour interview at the sumptuous, art-filled temporary two-story beachfront pavilion he and Marino built, at a cost of millions, to promote the revitalized Raleigh. “In the world of preservationists, I’m a purist. If we’re going to do all of this work, we’re going to go into the original design. If you’re going to do something, you have to do it right or not do it at all.

“My view on buildings and architecture is quite simple. We are building these for people, and people want one of two things — either a brand-new building, or an amazing historical building that has been restored but operates like a brand-new building. That is in essence what we are doing here.

“A lot of people think preservation is not the right way to go and just demolish and build all new, but there’s massive advantages to preserving and restoring. Old, historically significant buildings are irreplaceable. You can’t replicate the Raleigh. You can’t replicate the Transamerica Pyramid. You can’t replicate 530 Broadway. It doesn’t exist,” he said.

But you can replicate the Raleigh’s Martini Bar.

It’s there in the sales pavilion, where Shvo and Marino have constructed a fully working clone to the minutest detail. The expansive pavilion, in fact, functions as a clubhouse for Shvo, his marketing staff and prospective buyers, with a kitchen led by a Michelin-starred chef he declined to name.

So private is the pavilion that Shvo did not allow a Miami Herald photographer to take pictures of him that would show its interior in the background. (Shvo also tried to direct the photographer in others ways, asking him to show the right side of his face, and did not permit him to take a portrait showing the Raleigh pool because it was only half-filled with water.)

As Shvo spoke, servers wearing black gloves circulated in whisper-quiet fashion, discreetly filling water glasses and serving coffee after bringing out a three-tiered tray laden with deviled eggs with caviar, hummus with crackers, and cucumber and pureed salmon — a preview of the “great experiences” he promises Raleigh guests and residents.

If nothing else, Shvo is known to underlings and collaborators alike for his unstintingly demanding approach to, well, everything.

“The first and foremost thing about service is consistency, right? You have to have good service, but it has to be consistent,” Shvo said. “It has to be. When they serve these canapes and when they serve that egg, that egg better be served the same exact way every time, and it’s got to taste the exact same way. That’s true luxury, true service.

”We don’t just talk about it. The feeling, the touching, the seeing is a lot more powerful.”

Going well beyond the Raleigh

All that, however, isn’t enough to satisfy Shvo. As it turns out, his plans for Miami Beach now have veered well beyond just the Raleigh.

He has unveiled and received city design and historic-preservation board approvals for three South Beach office developments, all of them, not incidentally, within walking distance of the Raleigh. Two would be built from scratch. The third is a total-gut makeover of the prominent but decidedly dark and unlovely “clock tower” building on Lincoln Road Mall. It’s so nicknamed because of the digital time display at the top, which stopped working sometime during the COVID-19 pandemic.

He embarked on the ventures for a simple reason. He couldn’t find decent office space for himself anywhere near the Raleigh. An Israeli native who has lived in Manhattan since 1995, Shvo wanted something nearby that he could walk to but also met his standards. He doesn’t want to go to Brickell or downtown Miami, or sit in traffic on the MacArthur.

Nor do the elite, wealthy New Yorkers who came to Miami Beach during the pandemic, settling mostly in a narrow band of the city on the Sunset Islands and North Bay Road. It occurred to Shvo that his luxe-first approach to office redevelopment might appeal to them, too.

He’s betting that, like him, while sun and surf and hedonistic comfort lured the hedge-funders and investors from the moneyed elite for a spell during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s the ability to also work in suitably opulent surroundings that will make them stick around.

“I came here and I couldn’t find an office for myself worthy of anything. There was just bad product,” he said. “There is a small area where a lot of the wealthier New Yorkers came to during COVID. None of these people want to sit in cars for 45 minutes to go to work.”

Soon there were new acquisitions, new plans. The 1957 clock tower, not considered historic or architecturally notable, will be completely remade by Karp and the firm of Pritzker Prize-winning British architect Norman Foster. A new clock will adorn its roofline. Across Washington Avenue and Soundscape Park, Shvo bought a small commercial building, also non-historic, that will be demolished and replaced by boutique offices designed by Marino and Karp.

Foster and Karp are also working on a new green office complex that will occupy most of a city block on Alton Road at the other end of the mall, including the site of the long-gone Epicure Market.

And, Shvo said, he’s eyeing at least one more site for offices.

“We are building almost 400,000 square feet of office in Miami Beach. All of the projects are full-steam ahead,” Shvo said. “There is a reason why I’m getting great support from everybody, because there is a true understanding that the work we’re doing right now is so important for the future of the city.”

Beach voters recently turned down, by large margins, plans to redevelop city parking lots abutting Lincoln Road Mall into office buildings — along with a plan by New York mega-developer and Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross for a zoning-busting pair of hotel and residential towers to replace the demolished, historic Deauville Hotel in North Beach.

‘There is no better time’

For Beach leaders long looking to diversify the city’s economy beyond often-cyclical tourism and capricious, wealthy part-timers, Michael Shvo may be the man.

Shvo is not seeking use of publicly owned land or big zoning variances for his office projects. And he said he’s willing to follow his gut.

Taking advantage of what were then still low interest rates, he and his partners spent billions purchasing office buildings in the midst of the pandemic, including the Transamerica tower. They bought it for $650 million, regarded in the industry as a significantly discounted price. They then sank another $250 million into renovations.

Shvo intends to keep doing so even as interest rates rise and office markets crater in New York and San Francisco, while many continue to work remotely. Prime, historic buildings will hold their value, even increase faster than new or nondescript ones, and he plans to own them for decades, Shvo said. And, noting the office market is thriving in Miami as a whole, he thinks demand will be strong in Miami Beach as well for what he plans to offer.

“An office in Miami Beach and an office in New York are two different conversations,” Shvo said. “There is no better time. Look, buying real estate assets, great assets, is not something you can time. These are things that rarely become available. It is like somebody digging in a mine through diamonds. When a diamond comes, it comes. With the Raleigh, the stars were aligned. When Tommy Hilfiger had financial issues, that’s when we had the opportunity to buy it.

“We have done billions of dollars worth of deals through that period [COVID-19], which was, looking back, a great move. At the time, it was thought somewhere between crazy and courageous, depending what you think.”

Gelber, the Beach mayor, thinks what Shvo’s planning is right for his city.

“I’m a good example. I’ve been a lawyer for 40 years. I’ve never had an office on Miami Beach, always Brickell and downtown. And a lot of our residents make that commute every single day,” Gelber said. “Growth by itself is not necessarily, intrinsically positive, unless it improves your economy. And we have an opportunity to diversify our economy. It’s good for the city, as well as our transportation challenges. Having more than just hospitality here is a good thing.”

Shvo has advanced his projects with a relative minimum of fuss, somewhat unusual in a city known for fractious battles between developers and residents over redevelopment and preservation. He is one of several outside developers, including Alan Faena of Argentina, fellow New Yorker Jason Halpern and Doronin, Shvo’s partner at the Aman New York, who are winning plaudits for combining meticulous preservation with compelling new construction on the Beach.

“When you understand how to work with the community in Miami Beach, you can work wonders here,” he said. “If you’re not cooperating with the historic preservation board, it could be a true challenge.”

Harming Miami Beach skyline?

Not everyone’s a fan, though.

One prominent Beach preservationist, former longtime preservation board member and chair Jack Finglass, was the lone vote against Shvo’s plans for the Raleigh. He has criticized the city’s willingness to give the developer the OK to reduce the South Seas and Richmond to their facades and build extra height for the Rosewood Residences condominium in a historic district created to preserve the original mid-scale skyline — even if Shvo’s restoration plan for the Raleigh itself is first-rate.

“The Raleigh could not be done better,” Finglass said. “I give him every kudo in the world. But what he has proposed there, and many others are also proposing, is slowly but surely destroying the historic character of the Miami Beach skyline. As you whittle it away, it will become like Sunny Isles. These developers use historic buildings as cannon fodder for aggressive new designs. They use the excuse it’s economics to pay for saving the historic building.”

That said, Finglass acknowledged the designs for Shvo’s new buildings are “gorgeous” and “spectacular” and those off the waterfront don’t bother him.

“He is not a villain. He is not undesirable. Some of the things he does are really good,” Finglass said. “Unfortunately, on the water, taxes and land value are so high, the developers feel they have to squeeze every dollar out of there. I do understand where they’re coming from. But I don’t want what they want.”

What has not been an issue in Miami Beach is Shvo’s tax-fraud case, which took two years to conclude.

In a 2016 indictment, New York prosecutors alleged Shvo, an art collector, bought artworks and a Ferrari with falsified records, including a sham corporation in Montana, to avoid paying $1 million in state sales, corporate and use taxes. Shvo pleaded guilty to several criminal charges in a deal with prosecutors.

Shvo stressed in the interview that the charges had nothing to do with his real-estate business. He won’t go into details. But no one on Miami Beach has brought up the case, he said.

“The whole thing is, you know, a non-issue,” Shvo said. “It made me stronger. It made me more focused. My business today is at the highest point it has ever been. I work today with some of the most conservative institutional partners out of Europe. We work with multiple German state pension funds, insurance companies.

“I am very fortunate to have the career where going to work is not really work. I love what I do. I wake up in the morning and I get to work with the likes of Norman Foster, with the likes of Peter Marino, with the likes of Renzo Piano, and really create some of the greatest buildings in the world.”

That he’s able to do so, Shvo said, is largely God’s doing. A devout and observant Jew who prays every morning and keeps the Sabbath, Shvo said he’s never planned ahead much in his life, yet it’s all somehow worked out.

“If you ask me how, when you go through challenges you have in life, and sometimes I talk to God and ask, ‘Why is this happening, why do I deserve this?’ And when you have strong faith, you understand you’re only seeing part of it,” Shvo said. “I didn’t plan anything, truly. God planned everything. I have proof.”

Arriving in America with no plan

The evidence: How he fared after an impulsive decision to leave Israel and fly to New York City as a young man with no plan and no prospects.

The son of two chemistry professors at Tel Aviv University, Shvo got a taste of America as a child when his parents did teaching stints and sabbaticals at MIT and Stanford. After his father died, he said the family was going through materials and mementos his mother had collected and found a drawing he did of the Transamerica tower during a visit to San Francisco, as if it were a premonition of his acquisition decades later.

“It is a picture of myself by the Transamerica pyramid drawn by myself in 1981,” Shvo said. “To answer your question, was this planned? It was all planned. It was planned forty years ago. The Transamerica pyramid was the symbol of the American dream. That was what I wanted to do when I grew up. Forty years later, I’m the custodian of this amazing building. It is such a privilege.”

What came years later was the stuff of numerous media profiles.

After the obligatory service in the Israeli military, and after he made and lost a small fortune trading stocks, Shvo said, he quit college to his professorial parents’ dismay and flew to New York in 1995 at age 23 on a whim with $3,000 in his pocket. He bought a cab and rented a medallion and set himself up in the taxi business, the first of a series of ventures he tried. None lasted long. He slept on friends’ floors, sometimes went without eating, until a neighbor helped him get a job as a real estate broker though he knew nothing about the business.

Within four years, he has said, he was the top broker in New York City at what is now the Douglas Elliman real estate empire, working 18-hour days and selling hundreds of millions of dollars worth of property, with a corps of agents working under him and sharing commissions with him.

“I had a full decade of just working, working, working. Hard work, hard work, and more hard work,” he recalled. “It was about strong self-control, because you don’t work for anybody, you work for yourself. Hopefully, I was maybe a little more talented than the next guy.”

When he noticed that many high-end condos and apartments were promoted cheaply — “a conference room with a plastic model with some pictures on the wall” — he went into marketing and promotion for himself.

In 2004, a friend, developer Shaya Boymelgreen, hired him to market a new condo he was planning in lower Manhattan. Brainstorming how to overcome a stagnant local real estate market after 9/11, Shvo said, he came up with the idea of hiring fashion designer Giorgio Armani to do the interiors as a marketing lure. That, he claimed, “changed the face of real estate,” starting the trend of marrying fashion and development. Soon Shvo was snaring high-flying clients in the Middle East and around the rest of the world. He had 120 people working for him.

And, having promised himself to quit at 35, he did. He idled his firm and devoted himself to art collecting and curating, with a particular fondness for the sheep sculptures of French conceptual artist Francois-Xavier Lalanne. He met and married his wife, Turkish model Seren Ceylan, now Seren Shvo. They have two young children.

The interlude lasted four years. “I retired from being retired,” Shvo said.

‘From dark moments comes light’

The siren that called to him was development.

In 2013, he bought an old Getty gas station in Chelsea for $23.5 million for a luxury condo project, his first collaboration with Marino, who had earlier turned down Shvo for another job. To promote the planned condo, called The Getty, Shvo installed a flock of Lalanne’s stone-and-epoxy sheep sculptures at the filling station.

The 12-story tower, with just six condos, including a penthouse that sold for $30 million, and each a different design, broke sale-price records.

“I do believe that everything I went through in life — I slept on the floor, I went without eating, I went through multiple things — nothing was handed to me. All of these different things led me to other things. This goes back to my faith,” Shvo said. “The same thing when COVID started. If I did not have faith, I would be like everybody else thinking the world was coming to an end — ’Do not think, fire all of your employees, furlough everybody, go home.’ But I didn’t do that. I did the exact opposite. I invested billions of dollars, because I knew that from dark moments comes light.”

The Getty also cemented what would be a long working relationship — and a close friendship — between Marino and Shvo. They are very different peas in a pod who nonetheless share an affinity for perfectionism, control and a florid if tasteful maximalism. The Wall Street Journal once described Marino’s design approach as “aesthetic overload.”

The two spend hours poring over samples of materials for their projects — rare stones quarried in remote locations, custom fabrics, exotic woods. Marino and Shvo spent two years on the renovation design for the developer’s condo at the former Time Warner Center, now Deutsche Bank Center, in Manhattan. During pandemic lockdowns, he and Marino spent weeks going over the designs for the Raleigh and the temporary pavilion, Shvo said.

Shvo said he’s the only developer Marino works for, because, he said, “I’m the only developer committed to building what he designs.”

Both affect a working uniform you might call men in black: Marino in custom-made head-to-boot motorcycle leathers, a style he adopted years ago, and Shvo in black slacks and shiny black leather shoes by Tom Ford and a black Giorgio Armani T-shirt, of which he has, depending on the interview, either 100 or 200.

Shvo said he threw out all his other clothes years ago to strip down the number of decisions he has to make every day. He also has the same exact thing for breakfast every day — a glass of celery juice, a publicist said, though he also mentioned coffee and an apple during the interview — and grilled salmon and veggies for lunch. If out for dinner, he prefers restaurants where he knows the offerings and doesn’t have to look at a menu.

Marino, traveling abroad for work for an extended period, was unavailable for an interview. But in an admiring 2016 feature as the Getty was opening, “Friday Night Lights” author and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Buzz Bissinger, himself a leather aficionado, called Shvo and Marino “relentlessly demanding personalities.”

Fortifying iconic hotel for next 100 years

At the Raleigh pavilion, the same intensity of attention to detail is on full display. Nothing seems out of place, not a stray piece of paper in sight. More than once, Shvo stood up as he spoke to shut a door someone left ajar.

Karp, the Miami architect on the project, said the perfectionism can sometimes slow things down.

“He has been a true gentleman to work with,” Karp said, but added: “He’s an obsessive-compulsive sometimes to the point where it’s a hindrance to him. Perfection is rarely achieved. That’s why he has people like me to move on and get things done.”

But Karp, a fellow Israeli who said he and Shvo hit it off when they met in Abu Dhabi in 2007, said the developer has also proven a quick and astute study. Karp, who started work on the plans before Marino came on board, said Shvo immediately got it when Karp suggested to him ridding the Raleigh, Richmond and South Seas of unsympathetic additions and finishes layered on during the years — including a penthouse added to the Raleigh’s rooftop at some point.

Pushing back the new condo tower to the edge of the beach and allowing extra height, concessions developed in negotiations with the city and preservation board, means the three historic hotels will stand out independently, instead of being overshadowed by the new 44-unit tower.

“I told him, demolish all the appendages and the horrendous additions. Tommy couldn’t figure out what to do, but Shvo got it in a minute,” Karp said. “That allowed us to design a new tower, while leaving the Raleigh to do a historic preservation.”

That focus will allow Shvo to bring back to authentic life what’s widely regarded as a unique gem among South Beach’s pre-World War II hotels and some of the richest interiors in Miami Beach.

Inexplicably inspired by a Walter Raleigh theme, the hotel’s builders and architect Dixon married a streamlined style of Art Deco to baroque details like the famous swimming pool, supposedly shaped like the doomed Elizabethan explorer’s coat of arms, and lobby frescoes of Sherwood Forest, which Shvo said were too damaged to save and have been removed.

But the rest of the two-level lobby, including rich wood paneling and original terrazzo floors will be fully restored.

There also will be substantial investment in protecting the Raleigh in the face of a modern threat that Dixon never had to contend with — rising seas and increased storm surge. Flood gates and devices to collect water will be installed in the hotel’s basement to minimize potential damage to the historic structure.

“The obsession in historic preservation is about, to what level are you willing to go?” Shvo said.

“It is to me truly to peel back all of the layers of the onion, to expose the heart, expose the original design from the original drawings that we have from L. Murray Dixon. You are going to see it the way it was supposed to be built. It is very important to me that when we are done with this property that we walk down Collins Avenue or walk into the lobby and you can actually see what was designed in the 40s.

“And then we’re doing everything possible to make sure it is also built for the next 100 years,” he said.