Bonded through atrocity, men set out to correct record of Louisiana's Colfax Massacre

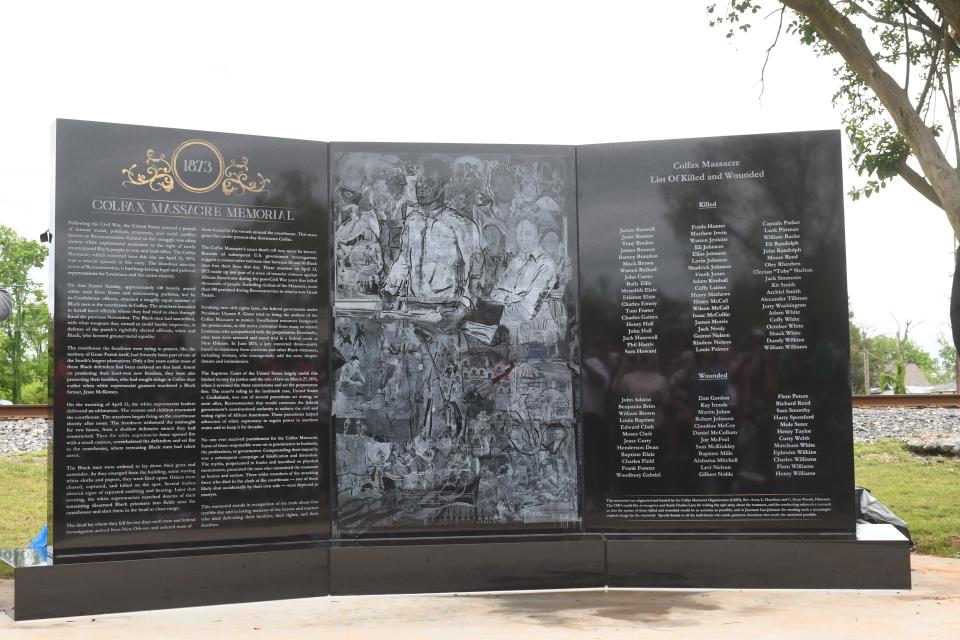

COLFAX, La. – The shiny new black marble monument dedicated to the victims of the Colfax Massacre sits next to the railroad tracks on Eighth Street, not far from where the atrocity took place on April 13, 1873.

“The monument is a reminder of the power of memory and a sacrifice made by those who came before us and the ongoing struggle for a more just and equitable society,” the Rev. Avery Hamilton told a crowd gathered for the monument’s dedication ceremony last week, in the small community about 120 miles southeast of Shreveport, Louisiana.

With the Colfax Massacre Memorial, the Colfax Memorial Organization seeks to correct the historical narrative of racial injustice that took place on that fateful day. The organization was co-founded by Hamilton and Dean Woods of Houston, Texas.

Etched on the monument are the names of the men who were part of an all-Black state militia killed or wounded that day defending the Grant Parish Courthouse from a white mob upset about the results of a statewide election. About 60-80 Black men were said to be killed though the exact number is unknown. Three white men were also killed.

The ancestors of Hamilton and Woods were on the opposite sides of what Woods said was “one of the most monumental and bloodiest massacres in American history.”

The first Black man killed in the massacre was Jesse McKinney, the great-great-great grandfather of Hamilton. He found out about his relation to the Colfax Massacre and McKinney after researching his genealogy.

The great-grandfather of Woods, Bedford Eugene Woods, was one of the perpetrators. Woods also found out about his ancestor through genealogical research.

A hushed story

Hamilton has lived in Colfax his whole life but said the story of the massacre was barely mentioned or discussed.

“It was never taught in schools. It was mentioned in hushed tones in the white and the Black communities. No one really talked about what happened here,” he said. “Outside of a few people making comments here and there, no one talked about this, so no, I didn't know this story growing up.”

Huey Tademy is a descendant of a few of the men who were massacred. He said they had no factual information about the massacre when he was growing up either.

Avery Hamilton’s father, Tom Hamilton, said they heard a lot of verbal accounts about the massacre growing up but even those were confusing.

What Avery Hamilton said he and others knew of the massacre was only what was written on an old historical marker that used to be in front of the Grant Parish Courthouse.

The marker, erected by the Louisiana Department of Commerce in the 1950s, read “Colfax Riot: On this site occurred the Colfax riot in which three white men and 150 Negroes were slain. This event marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

Deemed offensive and inaccurate, that marker was taken down by the state in 2021.

Shocking information

Woods grew up in Shreveport. Though his family visited relatives in Montgomery, about 15 miles northwest of Colfax, he and his sister never heard of the Colfax Massacre or even the mention of their great-grandfather's name.

It was while researching his family that Woods was shocked to find out about his great-grandfather's involvement.

The obituary for Beuford Eugene Woods who died in 1921 states that he was a proud member of the Veterans of the Colfax Race Riot of which he was the treasurer. That both stunned and saddened Woods.

“Whether he had even fired a shot, to the end of his days, he was proud of what he and the other men had done that day to end the lives of so many brave men,” said Woods.

Woods said that he did not know what to do with this information.

“What do you do when you find out one of your ancestors was involved in a horrific massacre,” he said. “Do I tell anybody? Do I just ignore it? What do I do?”

Woods sought more information about the atrocity

He wanted to learn more about this tragedy so he first read the fictional “Red River” by Lalita Tademy. Then Charles Lane’s “The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction,” and “The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror & the Death of Reconstruction” by LeeAnna Keith.

“Through these books, I learned details about the massacre and its aftermath,” he said, which had far-reaching implications for Black people across the country for over a century.

The Colfax Massacre

The Colfax Massacre has been known as the “Colfax Race Riot” or the “Easter Sunday Massacre.”

A 2003 article in the Alexandria Town Talk, part of the USA TODAY Network, states that “according to several historical studies, the massacre happened after tensions grew between whites and Blacks during the Reconstruction era between 1865-1877.”

It was during this time that Louisiana had a Black lieutenant governor, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, who later became the first Black governor after the impeachment of Gov. Henry Clay Warmoth due to political corruption plaguing his administration.

The article goes on to say that Black residents outnumbered white residents in Colfax. Hate groups like the White League, the Ku Klux Klan and former Confederate soldiers moved in upset over the results of the statewide election. The mob killed many of the Black men at the Grant Parish Courthouse during the fight and even killed those who surrendered.

Ushered in Jim Crow laws

The article also states that a U.S. attorney obtained convictions against the white men who killed the Black men “under laws designed to protect newly freed slaves from violence and intimidation.”

But the U.S. Supreme Court decision in U.S. vs. Cruikshank overturned the convictions in 1876 and freed the white men convicted. The decision became one of a series of rulings that limited the federal power to enforce the post-Civil War amendments and legislation. That allowed Southern states to enact laws that took away protections given to Black Americans after the Civil War.

Because of this, the Colfax Massacre was said to be pivotal in ushering in Jim Crow laws which legalized racial segregation through state and local laws across the South.

“This narrow interpretation of federal Civil Rights authority created a precedent that made future prosecutions of such violent deeds in the South more difficult to sustain,” said Lane, who was the featured speaker for the ceremony. “These precedents helped advocates of white supremacy regain power in Southern states and keep it for decades."

The old historical marker

After realizing how big and important this atrocity was for Black people, Woods said he wanted to do something. So he started with the old historical marker.

“To me it was just so offensive that an inaccurate marker like that stood for 70 years and had been seen by so many people who were misled that it was a race riot rather than a massacre,” said Woods.

He learned that many dedicated people like Hamilton tried to get it taken down. Jeff Crawford and Tom Barber who were students at Louisiana State University started the effort to get it removed.

Woods found out the Grant Parish Police Jury controlled the land where the marker stood. He called and sent a letter to the agency in Louisiana which had control over the marker. That’s how he met Mandi Mitchell who worked with Louisiana Economic Development at the time.

“She’s the one who had the political savvy to know how to handle the situation,” said Woods.

Mitchell met with the Police Jury, telling them that even though the marker was on the courthouse grounds which belongs to the parish, the marker belongs to the state and since it was not historically accurate, it had to be removed.

After a couple of legal letters going back and forth, Woods said the Police Jury agreed to take it down but didn’t want another marker put up because they didn’t want to deal the accuracy of history one way or another.

Mitchell told the crowd at the ceremony that the old marker would be placed in the future Louisiana Civil Rights Museum.

The marker had to come down, Gov. John Bel Edwards emphasized to the crowd as he spoke during the ceremony.

Every day that marker was up, he said it meant the state of Louisiana was complacent in telling Black residents in Colfax and everywhere else to “stay in your place because if you don’t, this is what could happen.”

“And for good measure they put a score on it, 150 to 3. 150 to 3,” said Edwards.

During the ceremony, Lane told the crowd that an obelisk was constructed in 1921 and dedicated to the perpetrators of the massacre. He said the inscription on it reads, “that it honored the men that fell fighting for white supremacy.”

“That much of the inscription is true,” said Lane. “It also calls them ‘heroes.’ But that word far better applies to the men who defended the courthouse a century and a half ago.”

Something else needed to be done

Woods and Hamilton began talking about next steps in May 2021 and came up with the idea of a memorial instead of another marker.

When the men finally met, they immediately formed a bond.

“Me coming from one of the perpetrators’ families and him coming from the first man murdered,” said Woods. “We just felt like something needed to be done besides just taking the marker down and we slowly talked about a lot of things during those days.”

With Mitchell’s help, the two men began working towards that effort by starting the non-profit Colfax Memorial Organization and making it into a 5013C.

Woods credited Lane with vetting the names of those were were killed and wounded that were to be etched on the monument.

For years, Lane, a columnist and editor for the Washington Post, has researched and written about the Colfax Massacre.

Now that the memorial is fully funded, they are seeking donations for a scholarship program for Black students in Colfax, said Woods. They want to change lives for the better.

“And hopefully that might help Colfax prosper into the future,” Woods said.

Of the descendants of the perpetrators, Tademy said he holds no grudge against them because they were not there and are not to blame for their ancestors’ actions.

“We can’t blame them for history. The thing we have to do is try and better the conditions and work along with each other,” he said.

“Let the past be the past,” said Tom Hamilton.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Colfax Massacre descendants set out to correct historical account