Late boneset, despite its name, won't heal bones but does attract pollinators | Mystery Plant

Most people in Florida, if asked politely, would probably not be able to tell you the name of a field botanist in their area.

Now, there are quite a number of different kinds of people who study plants, whether trained formally in an academic setting or not, including agronomists, plant physiologists, horticulturists, geneticists, and even backyard gardeners.

There are also what we call “plant taxonomists” who concern themselves with the naming and classification of plants, sometimes involving very sophisticated (and useful) scientific instrumentation and techniques.

Native sunflowers: Sunny bouquet: Native perennial sunflowers provide critical food source

Mystery Plant: These two red-blooming vines can be annoyingly invasive

Birdsong: Find bulbs and other treasures at Birdsong Nature Center's Old-Timey Plant Sales

But then there is a subset of taxonomists who spend most of their time tromping around outdoors, swatting bugs and sweating, and actually observing plants where they grow, thus accurately establishing and cataloguing their distribution and ecology: these are field botanists.

And, field botanists often collect samples of the plants they are observing, making sure that the collections end up in a curated collection somewhere — and of course, this collection is called an “herbarium.”

After what might seem to be a somewhat overextended period of academic training, I myself have ended up as a plant taxonomist, and at this point I suppose that I must be a “field botanist.” I hope you know one or two.

So, there I was last week as a field botanist, several counties away from my home, finding myself at the edge of a country road, and under a very wide set of powerlines. This powerline has a right-of-way (that is, the occasionally mowed width of ground below the lines) of nearly 200 feet.

Both sides of the right-of-way are bordered by forested land, and as you might expect, the vegetation beneath powerlines can be much different from that within a nearby forest, mostly due to the amount of light available in the open space.

Lots of opportunities for native as well as introduced plant species, and therefore, a high potential for considerable plant species diversity.

Our Mystery Plant was there: Late boneset, White boneset, Eupatorium serotinum.

It’s a native member of the aster family, growing to be about 3 feet tall, with handsome lance-shaped leaves, toothy (usually) along the edges. The leaves are opposite on the stem (two at each node). The flowers, as with everything else in its family, are quite tiny, congested into little heads, each head wrapped around with a spiral of tiny bracts.

Each of these heads contains 10 or so tiny white flowers, and since there can be hundreds of heads, there are usually many, many flowers needing to be pollinated. And pollinators like this plant: butterflies and bees.

Because it is a lovely native over most of the eastern USA, attracting lots of pollinators, and because it isn’t too fussy about where it grows, it ought to make a good garden plant. Don’t you think?

Something else: this species and some of its relatives have been named “boneset” — an old common name suggesting medicinal properties. In fact, the plants are no good for mending broken bones, but may have proven useful as teas for alleviating fevers causing bone and joint aches.

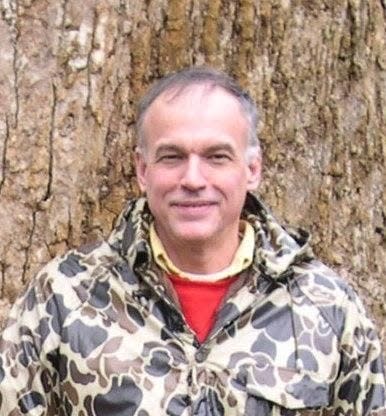

John Nelson is the retired curator of the A. C. Moore Herbarium at the University of South Carolina in Columbia SC. As a public service, the Herbarium offers free plant identifications. For more information, visit herbarium.org or email johnbnelson@sc.rr.com.

Never miss a story: Subscribe to the Tallahassee Democrat using the link at the top of the page.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Mystery Plant: Late boneset attracts bees and butterflies