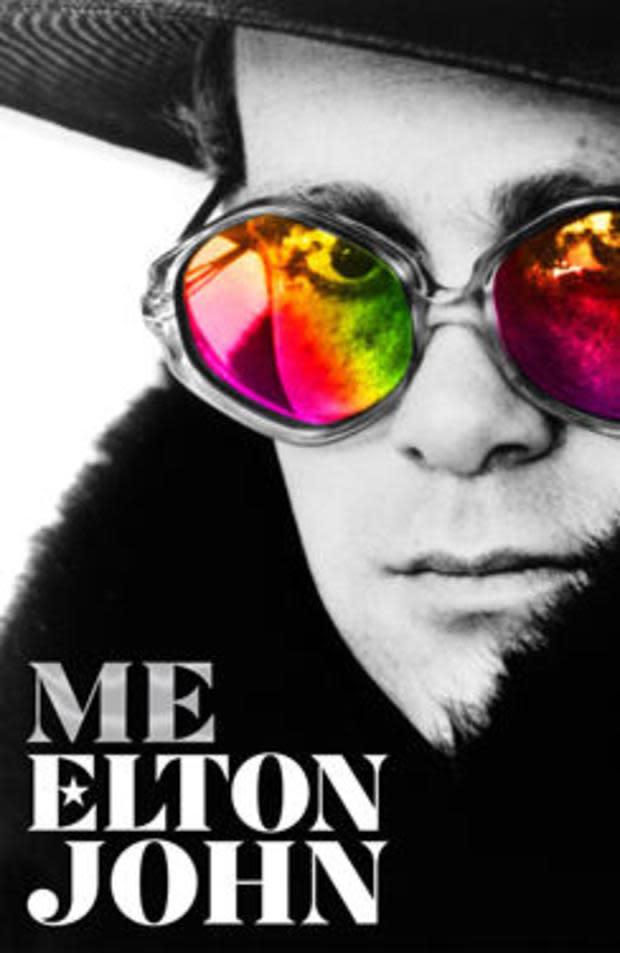

Book excerpt: "Me" by Elton John

This article, Book excerpt: "Me" by Elton John, originally appeared on CBSNews.com

In this excerpt from "Me," his first official autobiography (published this week by Henry Holt and Co.), music legend Sir Elton John writes of exiting the comfort zone by composing songs for "The Lion King"; meeting his future husband; and how the world avoided an Elton John theme park.

Don't miss Tracy Smith's interview Elton John on "CBS Sunday Morning" October 13!

I don't want to sound mystical – or even worse, smug – but it was sometimes hard to escape the feeling that life was patting me on the back for getting sober. "The One" became my biggest-selling album worldwide since 1975. After two years, the renovations at Woodside were finished and I moved back in. I loved it. It finally looked like somewhere a normal human being might live, rather than a coked-up rock star's preposterous country pile. Ten years after we'd last written a song together, Tim Rice phoned up out of the blue, asking me if I was interested in working with him again. Apparently Disney were making their first animated film based on an original story rather than an existing work, and Tim wanted me involved. I was intrigued. I'd written a movie soundtrack before, for "Friends," a 1971 film that got some pretty hair-raising reviews – I remember Roger Ebert calling it "a sickening piece of corrupt slop," but not all the critics enjoyed it as much as that. I'd given soundtracks a wide berth ever since, but this was clearly something different. The songs had to tell a story. The plan was that we wouldn't write the usual Broadway-style Disney score, but try and come up with pop songs that kids would like.

Henry Holt & Co.

It was a strange process. Tim wrote the same way as Bernie, lyrics first, so that was fine. In fact, writing a musical was like writing the "Captain Fantastic" album, because there was a storyline: there was a specific sequence that you had to follow; you always knew in advance which order the songs had to go in. But I would be lying if I said I never had doubts about the project or, rather, my place within it. I have many flaws, but being an artist who takes himself too seriously is something you could never accuse me of. Even so, there were days when I'd find myself sat at the piano, thinking long and hard about the path my career seemed to be taking. You know, I wrote "Someone Saved My Life Tonight." I wrote "Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word." I wrote "I Guess That's Why They Call It The Blues." And there was no getting around the fact that I was now writing a song about a warthog that farted a lot. Admittedly, I thought it was a pretty good song about a warthog who farted a lot: at the risk of appearing big-headed, I'm pretty sure that in a list of the greatest songs ever written about warthogs who fart a lot, mine would come in somewhere near the top. Still, it felt a long way from The Band turning up backstage and demanding to hear my new album, or Bob Dylan stopping us on the stairs and complimenting Bernie on "My Father's Gun." But I decided that something about the sheer ridiculousness of the situation appealed to me, and carried on.

It was the right decision. I thought the finished film was completely extraordinary. I'm not the kind of artist who invites people over to play them my new album, but I loved "The Lion King" so much that I arranged a couple of private screenings so friends could see it. I was incredibly proud of the whole thing; I knew we were on to something very special. Even so, I couldn't have predicted that it would become one of the highest-grossing films of all time. It introduced my music to a completely new audience. "Can You Feel The Love Tonight?" won an Oscar for Best Original Song: three of the five nominations in that category had come from "The Lion King": one of them was "Hakuna Matata," the song about the farting warthog. The soundtrack sold eighteen million copies – more than any album I've ever released except my first "Greatest Hits" collection. As an added bonus, it kept "Voodoo Lounge" by The Rolling Stones off the number one spot in America all through the summer of 1994. I tried not to be too delighted when I heard that Keith Richards was furious, grumbling about being "beaten by some f****** cartoon."

The Lion King - Can You Feel The Love Tonight by DisneyMusicVEVO on YouTube

Then it was announced that they were turning it into a stage musical, for which Tim and I were asked to come up with more songs. Once more demonstrating my uncanny ability to predict exactly what isn't going to happen, I kept telling people that turning an animated film into a stage show was both impossible and doomed to failure – I couldn't see it at all.

But the director, Julie Taymor, did an amazing job. It opened to rave reviews, was nominated for eleven Tony Awards, won six, and became the most successful theatrical production in the history of Broadway. The whole thing looked astonishing – the sheer ingenuity they had used in staging it was breathtaking, but I still found the experience of actually sitting through it oddly awkward. It had nothing whatsoever to do with the show itself. It was just that I was used to making albums where I had the last word, or to being completely in charge of my live shows. Here was something I'd helped create, and yet once it was onstage, it was unfolding completely out of my control. The arrangements were different from the way I had recorded the songs, and so were the vocals. In musical theatre, every word has to be clearly enunciated, it's a completely different way of singing to anything a rock or pop artist does. It was a totally new experience for me: simultaneously amazing and slightly unnerving. I was completely outside of my comfort zone, which, it slowly dawned on me, was an extremely good place for an artist to suddenly find himself, forty years into his career.

Disney were absolutely overjoyed with "The Lion King"'s success – so overjoyed, they came to me with a deal. It was for a ridiculous amount of money. They wanted me to develop more films, do TV shows and books; there was even some talk about a theme park, which boggled the mind a little. There was just one problem. I'd agreed to make another film with Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had been chairman of Disney when "The Lion King" was made but then left a few months after the film was released and set up DreamWorks with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen. But he didn't just exit: his leaving prompted one of the great Hollywood wars between studio executives, so epic that people have literally written books about it. The Disney deal was exclusive: it was particularly exclusive of anything involving Jeffrey, who was now suing them for breach of contract and $250 million, which he eventually got. There wasn't anything in writing with Jeffrey, but I'd given him my word – he was one of the people who had brought me in to "The Lion King" in the first place. So I regretfully turned Disney's deal down. At least the world was spared an Elton John theme park.

But while my world still seemed to be full of new ideas and opportunities, the one thing sobriety hadn't helped at all was my love life. My relationship with John Scott had petered out some time before, and since then: nothing. I tried not to think about how long it was since I'd last had sex, in case the sound of me howling in anguish frightened the staff at Woodside.

I realized that I didn't really know any available gay men. When I got sober, I stopped going to the kinds of places I might meet them. I didn't think I'd be tempted to have a vodka martini if I went to a club or a bar, but there didn't seem any point in testing this theory. And besides, even before I'd gone into rehab, I'd begun thinking I was getting a bit old for that sort of thing. I'm sure the music at Boy would have sounded as wonderful as ever, but there does come a point where, in that environment, you start to feel like the dowager duchess at the debutantes' ball, peering down your pince-nez at the latest arrivals.

It all came to a head one Saturday afternoon, when I was rattling around the house feeling thoroughly sorry for myself. I had one eye on the football, where Watford were doggedly trying to make my mood worse by getting hammered 4–1 away at West Brom. I was contemplating another thrilling evening in front of the TV when I came up with an idea. I rang a friend in London and explained my predicament. I asked if he could round some people up and invite them to come to dinner that evening. It was short notice, but I'd send a car to London for them. As I said it, I realized that it all sounded a bit pathetic, but I was desperate to meet some gay men who weren't in Alcoholics Anonymous. I wasn't even looking for sex, I was just lonely.

They turned up around seven: my friend and four guys he'd roped in. They said they had to leave early to get to a Halloween party back in London, but I didn't care. Everyone who had come along seemed really nice. They were funny and chatty. We ate spaghetti bolognese and had a great laugh – I'd almost forgotten what it was like to have a conversation that didn't revolve around either my career or sobriety. The only one who didn't seem terribly pleased to be there was a Canadian guy in a tartan Armani waistcoat called David. He was clearly shy and didn't say much, which I thought was a shame: he was very good-looking. I later discovered that he'd heard a lot of gossip on the London gay scene about the inadvisability of having anything whatsoever to do with Elton John, unless you had a burning desire to be showered with gifts, forced to put your life on hold in order to be whisked away on tour, then summarily dumped – usually by his personal assistant – when he met someone else, or lost his temper with you during a post-cocaine comedown, or announced he was getting married to a woman. I should have been outraged, but, taking into account my past behaviour, the gossips of the London gay scene had a point.

Eventually, he volunteered the information that he was interested in film and photography, which got the conversation going. I offered to give him a tour of the house and show him my collection of photographs. The more I talked to him, the more I liked him. He was quiet but self-assured. He was obviously very smart. He said he was from Toronto but had moved to London a few years before. He lived in Clapham and worked for the advertising company Ogilvy and Mather in Canary Wharf – at thirty-one, he was one of their youngest board directors. I thought I could sense something resonating between us, a flicker of chemistry. But I tried to put it out of my mind. The new, improved, sober Elton John wasn't going to decide he'd fallen madly in love with someone within minutes of meeting them.

Still, when it came time for them to leave, I asked for his number in what I thought was a casual way, suggestive merely of further stimulating conversations about our shared interest in photography somewhere down the line. He wrote his full name down – David Furnish – handed it over and off they went.

The next morning found me pacing around the house, trying to work out what was the earliest you could call someone who'd been out the previous night at a Halloween party, without looking like the kind of person they'd eventually have to get a restraining order out against. I decided eleven thirty was reasonable. David picked up. He sounded tired, but not entirely surprised to hear from me. It transpired that my casual request for his number hadn't looked quite as casual as I thought. Judging by the reaction of his friends, who'd spent the entire journey back to London mercilessly teasing him and singing the chorus of "Daniel" at him, I might as well have dropped to my knees, tearfully grabbed his ankles and refused to let go until he handed it over. I asked if he wanted to meet up again, and he did. I asked what he was doing that evening, when I just happened to be in London. I behaved as if this was a remarkable coincidence, but frankly, if David had been in Botswana, I suspect I would have happened to be there that evening too: "The Kalahari Desert? What a stroke of luck! I've got a meeting there tomorrow morning!" I suggested he come over to the house in Holland Park, and I would order a Chinese takeaway.

I put down the phone, told my driver that my plans for the day had changed and we were going to London immediately. I rang the most famous Chinese restaurant I could think of, Mr Chow in Knightsbridge, and asked if they did deliveries. Then I realized I didn't know what kind of food he liked, so I played it safe and ordered an immense selection from the menu.

David looked a bit startled when the Chinese takeaway arrived, or rather didn't stop arriving – by the time they'd finished delivering all the boxes, the place looked like the squash court at Woodside before I had the auction – but other than that, our first date went incredibly well. No, I definitely wasn't imagining it, there really was something resonating between us. It wasn't just a physical attraction; our personalities clicked. Once we started talking, we didn't stop.

But David had some reservations about us getting involved. For one thing, he wasn't keen on the idea of being seen as Elton John's Latest Boyfriend, with all the attention that would bring. He had his own life, a career, and didn't like his independence being turned upside down because of who he was seeing. And for another, he was only half out of the closet. His friends in London knew he was gay, but his family didn't, and nor did his workmates, and he didn't want them to find out via a paparazzi photo in a tabloid.

So for the first few months our relationship was very quiet and discreet: we were, to use an old-fashioned phrase, courting. We mostly based ourselves at the house in Holland Park. Every weekday morning, David would get up and go to work in Canary Wharf, and I would head off to the studio or to do promotion for the album of duets I'd just released. I made a video for the version of "Don't Go Breaking My Heart" I'd recorded with RuPaul: for once, I actually looked happy while I was making a video. I was happy. There was something about the relationship that I couldn't quite put my finger on. Then I realized what it was. For the first time in my life, I was in a completely normal relationship, that felt equal, that had nothing to do with my career or the fact that I was Elton John.

Elton John, RuPaul - Don't Go Breaking My Heart (with RuPaul) by EltonJohnVEVO on YouTube

Each Saturday, we would send each other a card, to commemorate the fact that we had met on a Saturday, and – if you've eaten recently, you may want to skip to the next sentence in case you become nauseous – listen to Tony! Toni! Toné!'s "It's Our Anniversary." There were a lot of cosy dinners and clandestine weekends away. If I called him at work, I had to use a false name – George King, the pseudonym I'd used when I booked into rehab. I thought it was terribly romantic. A secret love! The only kind of secret love I'd had before was the kind you have to keep secret because the other person clearly isn't interested in you.

But much as I adored the idea of a secret romance, I was pretty hopeless at the practicalities of it. It quickly became apparent that after twenty-five years of earning a living by being as extravagant and OTT as possible, my notion of keeping things low-key was wildly at odds with everyone else's. If you're trying not to draw attention to a relationship, it's perhaps not the best idea to regularly send your partner two dozen long-stemmed yellow roses at work, particularly if he works in an open-plan office. With the benefit of hindsight, the Cartier watch was probably a mistake as well. It was so expensive that David had to wear it all the time. He couldn't leave it at home, in case his flat got burgled, because he didn't have any insurance. Questioned by his colleagues as to where it came from – and if it might in some way be linked to the fact that his desk suddenly looked like a stand at the Chelsea Flower Show – he invented a beloved grandmother back in Canada, who had recently died and left him some money in her will, then spent an awkward afternoon fending off a succession of sad smiles, supportive hugs and expressions of condolence. When we arranged a weekend in Paris and I went to meet him off his plane at Charles de Gaulle Airport, I was fully briefed about the need to go unnoticed by any photographers or fans who happened to be there. Waiting in the arrivals lounge, I became aware of a degree of nudging and pointing going on around me. By the time David appeared, I was in a state of considerable agitation.

"Get in the car quickly," I hissed. "I think I've been recognized."

David smiled. "Really? I wonder why?" he said, directing his gaze to my outfit. The clothes I had decided would enable me to pass unnoticed through the airport consisted of a pair of harlequin-check leggings and an oversized shirt decorated in brightly coloured rococo patterns, accessorized with an enormous jewelled crucifix around my neck. I could possibly have drawn more attention to myself, but only if I'd turned up with a piano and started playing "Crocodile Rock."

The leggings and the oversized shirt were by Gianni Versace, my favourite designer. I wore his clothes all the time. I'd discovered his little shop in Milan at the end of the eighties and immediately become obsessed. I thought I had stumbled across a genius, the greatest menswear designer since Yves Saint Laurent. He used the very best materials, but there was nothing starchy or po-faced about his designs: he made men's clothes that were fun to wear. My already high opinion skyrocketed when I was introduced to the man behind them. Meeting Gianni was almost weird, like finding out I had a long-lost twin brother in northern Italy. We were virtually identical: same sense of humour, same love of gossip, same interest in collecting, same unquiet mind. He couldn't switch off; he was always thinking, always coming up with some new way of doing what he did, which was everything. He could design children's clothes, glassware, dinner services, album covers – I got him to design the sleeve for "The One," which he did beautifully. He had exquisite taste. He would always know of a little Italian church down a side street that had the most beautiful mosaic work in the nave, or a tiny workshop that made the most incredible porcelain. And he was the only person I've ever met who could shop like me. He would go out to buy a watch and come back with twenty.

Gianni Versace's cover design for the Elton John album, "The One." MCA Records

Actually, he was worse than me. Gianni was so extravagant, that by comparison I looked like the embodiment of frugal living and self-sacrifice. He thought Miuccia Prada was a communist, because she had designed a handbag made from nylon, rather than crocodile or snakeskin or whatever preposterously opulent material he was working with that season. He would try and encourage me to buy the most outrageously expensive things.

"I 'ave found you the most incredible tablecloth, you must buy it, for dinner on Christmas Day. Made by nuns, it takes them thirty years to make, look at it, it's wonderful. It costs a million dollars."

Even I baulked at that. I said I thought a million dollars was perhaps a little excessive for something that would be completely destroyed the second anyone spilt a bit of gravy on it. Gianni looked horrified, as if he was considering the possibility that I might be a communist too.

"But Elton," he spluttered, "it's beautiful . . . the craftsmanship."

I didn't buy the tablecloth, but it didn't affect our friendship. Gianni became my closest friend. I used to love picking up the phone and hearing his voice, delivering its usual greeting: "'Allo, bitch." I introduced him to David and they got on like a house on fire. Of course they did; there was nothing not to like about Gianni, unless you designed handbags out of nylon. He had the biggest heart and he was hilarious. "When I die," he would cry dramatically, "I want to be reincarnated even more gay. I want to be super-gay!" David and I would exchange puzzled glances, wondering how that could conceivably be possible. There were leather bars on Fire Island less obviously homosexual than Gianni.

Sometimes, being in a normal relationship made me realize how abnormal my own life frequently was. I arranged a small lunch party, so David could meet my mother and Derf. By then our relationship wasn't secret anymore. Someone from David's office had spotted us getting out of a car outside the Planet Hollywood restaurant in Piccadilly. He'd been called in to see his boss, told him everything, then made plans to go back to Toronto for Christmas and come out to his family. I was incredibly nervous: David had said his father was very conservative, and I knew how horrific coming out could be if your family weren't supportive. In Atlanta, I'd had an affair with a guy called Rob, whose parents were very religious and anti-gay. He was a sweetheart, but you could tell the conflict between his sexuality, religion and his parents' views was constantly eating away at him. We stayed friends, and after we broke up he came to see me on my birthday and brought me some flowers. The next day, he walked onto the freeway and threw himself in front of a truck.

It turned out that David's family couldn't have taken the news better – I think, more than anything, they were pleased he wasn't keeping secrets from them anymore – but I had still held off as long as I could from introducing him to my mother. Ever since I broke up with John Reid, she had developed a habit of . . . not seeing off my partners exactly, but being cold towards them, making their lives and mine more difficult, as if she resented the presence of anyone who detracted attention from her.

But the problem with the lunch party wasn't really my mum. It was one of the other guests, a psychiatrist, who at the last minute informed me that his client Michael Jackson was in England, and asked if he could bring him along. This didn't sound like the greatest idea I'd ever heard, but I could hardly refuse. I'd known Michael since he was thirteen or fourteen: after a gig I played in Philadelphia, Elizabeth Taylor had turned up on the Starship with him in tow. He was just the most adorable kid you could imagine. But at some point in the intervening years, he started sequestering himself away from the world, and away from reality, the way Elvis Presley did. God knows what was going on in his head, and God knows what prescription drugs he was being pumped full of, but every time I saw him in his later years I came away thinking the poor guy had totally lost his marbles. I don't mean that in a light-hearted way. He was genuinely mentally ill, a disturbing person to be around. It was incredibly sad, but he was someone you couldn't help: he was just gone, off in a world of his own, surrounded by people who only told him what he wanted to hear.

And now he was coming to the lunch at which my boyfriend was scheduled to meet my mother for the first time. Fantastic. I decided the best plan was to ring David and drop this information into the conversation as nonchalantly as possible. Perhaps if I behaved as if there was no problem here, he might take it in his stride. Or perhaps not – I hadn't even finished nonchalantly mentioning the change in lunch plans before I was interrupted by an anguished yell of "are you f****** KIDDING me?" I tried to reassure him by lying through my teeth, promising that the reports he had heard of Michael's eccentricities had been greatly exaggerated. This probably wasn't very convincing, given that some of the reports of Michael's eccentricities had come directly from me. But no, I insisted, it wouldn't be as strange as he might expect.

In that respect at least, I was absolutely right. The meal wasn't as strange as I might have expected. It was stranger than I could have imagined. It was a sunny day and we had to sit indoors with the curtains drawn because of Michael's vitiligo. The poor guy looked awful, really frail and ill. He was wearing make-up that looked like it had been applied by a maniac: it was all over the place. His nose was covered with a sticking plaster which kept what was left of it attached to his face. He sat there, not really saying anything, just giving off waves of discomfort the way some people give off an air of confidence. I somehow got the impression he hadn't eaten a meal around other people for a very long time. Certainly, he wouldn't eat anything we served up. He brought his own chef with him, but didn't eat anything he made, either. After a while, he got up from the table without a word and disappeared. We finally found him, two hours later, in a cottage in the grounds of Woodside where my housekeeper lived: she was sitting there, watching Michael Jackson quietly playing video games with her eleven-year-old son. For whatever reason, he couldn't seem to cope with adult company at all. While all this was going on, I could see David though the gloom, sitting at the other end of the table, valiantly trying to make bright conversation with my mother, who was doing her bit to add to the strained atmosphere by spending most of the meal telling him that she thought psychiatry was a waste of time and money in a voice loud enough for Michael Jackson's psychiatrist to hear. Whenever she paused for breath, I noticed David glancing around, as if looking for someone who might explain what the hell he'd got himself into.

It didn't take an unexpected visit from Michael Jackson to make the world David was entering seem completely bizarre. I could make it seem that way myself, without any help from the self-styled King of Pop. Rehab had curbed most of my worst excesses but not all of them: the Dwight Family Temper seemed particularly resistant to any kind of treatment or medical intervention. I was still perfectly capable of throwing appalling tantrums when I felt like it. I think the first time David really saw one up close was the night in January 1994 when I was due to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in New York. I didn't want to go, because I don't really see the point of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I loved the original idea of it – honouring the true pioneers of rock and roll, the artists who laid the path in the fifties that the rest of us followed, especially the ones who got ripped off financially – but it quickly became something else entirely, a big televised ceremony with tickets that cost tens of thousands of dollars. It's just about getting enough big names involved each year to put bums on seats.

The smart thing would have been to politely decline the invitation, but I felt obliged. I was being inducted by Axl Rose, who I really liked. I had got in touch with him when he was being ripped apart in the press: I know how lonely it can feel when the papers are giving you a kicking, and I just wanted to offer some support. We got on great and ended up performing "Bohemian Rhapsody" together at the Freddie Mercury Tribute gig. I got a lot of flak for that, because a Guns N' Roses song called "One In A Million" had homophobic lyrics. If I'd thought it reflected his personal views, I wouldn't have touched him. But I didn't – I thought it was pretty obvious the song was written from the point of view of a character who wasn't Axl Rose. It was the same with Eminem: when I performed with him at the Grammys, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation gave me a really hard time, but it was obvious that his lyrics were about adopting a persona – a deliberately repugnant persona at that. I didn't think either of them were actually homophobes any more than I thought Sting was actually going out with a prostitute called Roxanne, or Johnny Cash actually shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.

So I went along to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. As soon as I got there, I decided I'd made a mistake, turned round and left, ranting all the way about how the place was a f****** mausoleum. I dragged David back to the hotel, where I immediately felt guilty for blowing them out. So we went back. The Grateful Dead were performing with a cardboard cut-out of Jerry Garcia, because Jerry Garcia wasn't there: he thought the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame was a load of bullshit, and had refused to attend. I decided Jerry had a point, turned round and left again, with David dutifully in tow. I had got out of my suit and into the hotel dressing gown when I was once more struck by a pang of guilt. So I got back into my suit and we returned to the awards ceremony. Then I got angry at myself for feeling guilty and stormed out again, once more enlivening the journey back to the hotel with a lengthy oration, delivered at enormous volume, about what a waste of time the whole evening was. By now, David's sympathetic nods and murmurs of agreement were starting to take on a slightly strained tone, but I convinced myself he was probably rolling his eyes like that at the manifest failings of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame rather than at me. This made it easier to decide – ten minutes later – that all things considered, we had better go back to the ceremony yet again. The other guests looked quite surprised to see us, but you could hardly blame them: we'd been backwards and forwards to our table more often than the waiting staff.

I'd like to tell you it ended there, but I fear there may have been another change of heart and furious return to the hotel before I actually got onstage and accepted the award. Axl Rose gave a beautiful speech, I called Bernie up onstage and gave the award to him, then we left. We drove back to the hotel in silence, which was eventually broken by David.

"Well," he said quietly, "that was quite a dramatic evening." Then he paused. "Elton," he asked plaintively, "is your life always like this?"

Excerpt from "Me" by Elton John, reprinted by permission. Copyright 2019 by Elton John. Published by Henry Holt and Co. All rights reserved.

For more info:

"Me: Elton John" (Henry Holt and Co.), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazoneltonjohn.comFollow @officialelton on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube

Tragic accident takes the life of a Chowchilla bus kidnapping survivor

Eliud Kipochoge breaks marathon barrier with race completed in under 2 hours

Simone Biles ties record for most world medals with 23rd victory