New book explores 4 myths about slavery outlined in 'My Old Kentucky Home.' Why it matters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In her carefully researched and beautifully written new book, historian Emily Bingham examines American slavery and its after-effects in the context of Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home," a song synonymous with the Kentucky Derby.

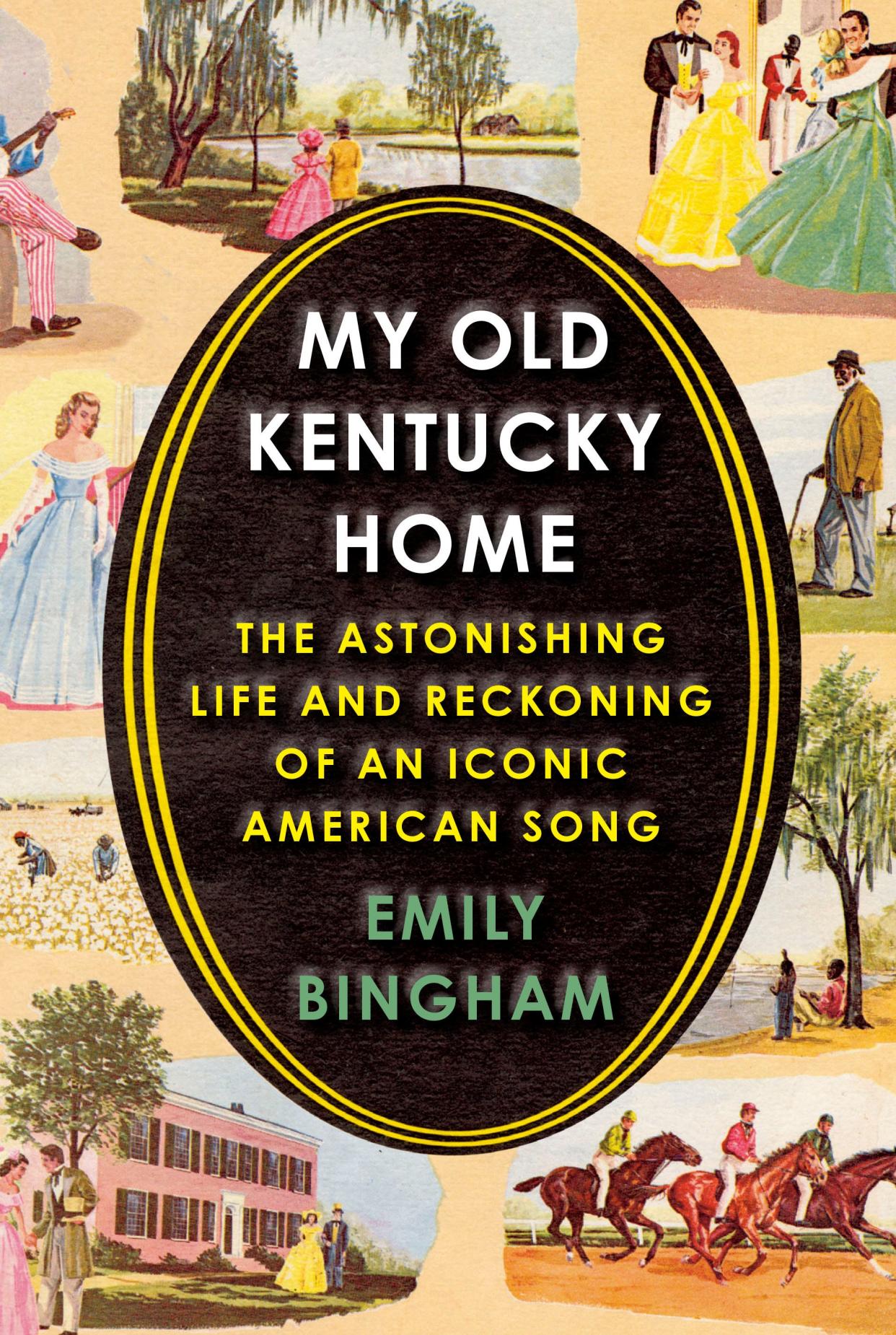

She intertwines it with deeply personal insights about her own evolution on racial issues as a historian by training and education, as a descendant of enslavers on both sides of her family, and as a daughter, spouse and mother. The book, "My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song," which will be released May 3, is riveting. It forces one to think carefully about Kentucky’s official state anthem and at a deeper level, it forces one to confront personal and societal racism.

Foster wrote his ballad in 1853 for use in burnt-cork blackface minstrel shows, a prevalent part of American musical entertainment at the time. As the lyrics reflect, it is the song of an enslaved man forced to leave his family in Kentucky when he is sold down the river to the field where the sugarcanes grow. Bingham notes that while “music is among the deepest means of human connection, it can also be a form of mind control.”

The ballad “encapsulates the United States’ contradictory and contorted relationship to slavery and white supremacy. We do not deny its reality, and the terror is plain to see. Nonetheless, Stephen Foster gave its victim a voice that sings that pain into nostalgia. Millions upon millions have sung along. This book is my effort to scrub it of its decades of nostalgia and burnt cork and confront what is underneath," Bingham says.

You may like: This more appropriate Stephen Foster song can replace 'My Old Kentucky Home'

Bingham deftly analyzes the making of at least four interrelated myths that have arisen from slavery through the lens of the ballad.

In writing what has become Kentucky’s legislatively approved anthem, Foster helped enshrine one of these myths: that enslavement in Kentucky was gay, merry, happy and bright in a place where the enslaved hunted for possum and coon, sang by the old cabin door in the glimmer of the moon where all was a delight. The reality explored by Bingham is one of brutality and terror over the enslaved by powerful white owners.

A second myth she examines is that spun by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the United Confederate Veterans, and other genealogy organizations that “the late unpleasantness” had nothing to do with slavery, and instead was a battle over the principle of states’ rights. This is the myth of the Lost Cause, advanced by pro-Confederate versions of history “by supporting scholarship, stocking library shelves with approved books and inserting their interpretation into statewide school texts” in order to correct “ ‘wicked falsehoods’ (including the idea that the system of bondage was cruel).”

The reality is quite the opposite.

A third myth analyzed by the author arises from the house and grounds of Federal Hill in Bardstown. Marketed to place Kentucky within a gauzy southern culture of white privilege by an enterprising descendant of the Rowan family, her husband, and state tourism officials in the age of motor tourism, a central part of the myth is that Foster wrote his iconic ballad while visiting the Rowan family at Federal Hill.

There is no evidence that he was ever there; the desk upon which he allegedly wrote the ballad was purchased in the 1920s, and there is no evidence that it was ever part of the Rowan family’s furnishings, nor has any architectural evidence of an original slave cabin been discovered.

Book review: 'A place that never was': Kentucky author Lee Cole pens memorable, timely debut novel

The house in which the ballad was claimed to have been written was no longer about the plight of the enslaved man being sold down the river. There apparently was never a little cabin with a bench by the door. Instead, the myth makers focused on the beauty of the house, its grounds and the nostalgic white southern culture that it symbolized.

A fourth myth addressed by Bingham is the perception of steady American progress on issues of race in the light of blindness and moral failure. As a young person, she believed that the road to a “level playing field” was steadily being paved.

“With small adjustments and goodwill, things were, as the Beatles song said, ‘getting better all the time.’ It’s a deeply American impulse, this faith in natural progress," she writes.

She sees this impulse as a possible obfuscation of less progressive history: lynchings, Jim Crow laws, police excess and the “new Jim Crow” of mass incarceration and other forms of institutional racism.

You may like: Gerth: A small Kentucky town is trying to remove a Confederate statue. That's a big deal

In a coda, Bingham discusses how in 2020, “My Old Kentucky Home” again became a matter of public debate following the Breonna Taylor and George Floyd killings and the ensuing protests here in Louisville and nationwide. This public debate occurred 34 years after the Kentucky General Assembly replaced an offensive word with “people” in the official version of the commonwealth’s anthem, an Act that was passed with the sponsorship of an African-American member of the Kentucky Senate.

She believes that this measure was, at best, an inadequate half measure. Two days before the running of the 2020 Kentucky Derby, Churchill Downs announced that “concrete action” would be taken to achieve “the changes America so desperately needs.”

At the 2020 Derby, the bugler played the notes to Foster’s melody. No words were sung. It remains to be seen what will happen next. The author suggests that the powerful voices of Black Americans should decide the circumstances under which “My Old Kentucky Home” should be sung in public spaces.

Because her personal and family experiences in so many ways parallel the song, this book can be characterized as a love letter — but one with tears in the eyes — to the commonwealth of Kentucky. The book also has a serious and important national reach.

In the author’s words: “I don’t believe it can be wrong to love a song, but I do believe we commit wrongs when we do not understand what we claim to love. Refusing to look closely at uncomfortable aspects of history has hurt this nation and may be its undoing. Eleanor Roosevelt used to tell college students, ‘Study history realistically. You’ll love your country just as much.’ In that sense, reckoning is also an act of patriotism…. Reckoning is an act of love.”

"My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song," by Emily Bingham, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2022, 233 pages.

Richard H.C. Clay is President and CEO of The Filson Historical Society.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: 'My Old Kentucky Home' by Emily Bingham book review