Book Look: 'Extreme Weather' reveals how nature wins wars or costs the lives of thousands

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Every once in awhile, I like to deviate from the review of a single book.

It occurred to me that people talk more about the weather than any other subject, regardless of where we live. It is either too hot or too cold, too wet or too dry, too windy or too still.

I researched the subject and concluded I could make the column interesting. I also found two books I can recommend if readers want to pursue this subject further.

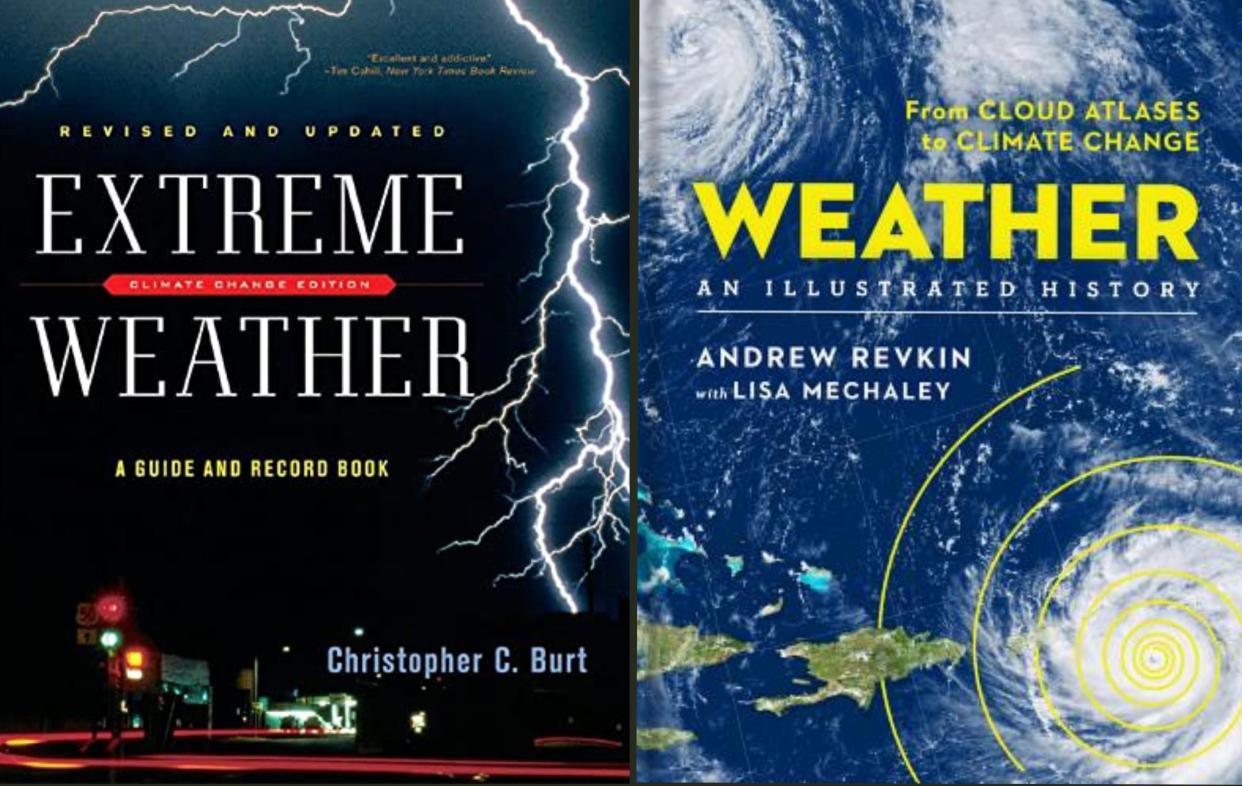

One book is "Extreme Weather, A Guide and Record Book" by Christopher C. Burt, published by W. W. Norton in 2004. It's 304 pages and costs $25.

The other is "Weather, An Illustrated History" by Andrew Revkin and Lisa Mechaley, published by Sterling in 2018. It's 212 pages and costs $24.95.

The book written by Burt has an incredible compilation of statistics, whereas the Revkin/Mechaley book selects major events and has short descriptions of each.

Most of the time, we view weather events as disasters, and when we look at weather events in our state, it appears that weather produces many disasters. The Children's Blizzard of 1888, the Armistice Day Blizzard of 1941, the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, the Rapid City Flood of 1972, and the Castlewood Tornado in 2022, to name a few.

However, the role of weather in some major events is less clear-cut. For example, in 1588, King Philip II of Spain sent his Spanish Armada to invade England. It seemed to be a cinch victory for the Spanish until gale-force winds of 70 to 90 mph struck the Spanish Armada, which had pinned the British Navy to a port where it was ripe for destruction. But it was the Spanish Navy on the high seas that limped back home with 75% of its fleet destroyed.

In 1812, a cocky Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia against the advice of his entire officer crew. Napoleon had many more troops, horses and guns than the Russians, but the Russians had 30-to-40-below-zero temps on their side. Napoleon ultimately abandoned his army and returned home on a one-horse sleigh.

Fast Forward to 1941. Despite having read the story of Napoleon, a very cocky Adolf Hitler asserted that the war against Russia would last only a few months and everyone would be home by winter. The army did not even take winter gear.

Italian journalist Curzio Malaparte wrote about the small percentage of the 320,000 soldiers who survived that winter and made it home.

Malaparte wrote, "The soldiers had no eyebrows. Thousands of them had lost arms and legs. Thousands had lost their ears, noses, fingers and sexual organs."

We are the United States of America because the Colonial Army had a lucky weather break.

Early in the Revolutionary War, the British surrounded the American Army under George Washington in Brooklyn and Manhattan. It already was a loss, and if the British captured Washington and his whole army, the war would have ended. Overnight, nature sent a dense fog cover, enabling Washington to evacuate his entire army across the East River without the British knowing.

If we often make jokes about errant weather forecasts on TV, our ancestors have been clueless throughout most of the world's history.

In 1815, the entire world turned dark when a long-simmering volcano in what is now Indonesia blew its top. The blast was heard 1,500 miles away and buried the earth's atmosphere in ash. It destroyed all crops on Earth. The blast killed thousands, and tens of thousands died from starvation because crops could not be grown. In addition, the Earth's temperature was severely affected. New England had snowstorms in June.

Speaking of temperatures, the invention of temperature and the resulting thermometer are among the most monumental inventions in the history of the world. It wasn't until 1603 that Galileo Galilei and others discovered how to tell the temperature. Just more than 100 years later, Daniel Fahrenheit invented how we standardize and measure degrees.

The first public weather forecast for ordinary citizens was published in The London Times on Aug. 6, 1861. It was a bit more "bare-bones" than today's forecasts:

"North England--Moderate westerly wind; fine. West England--Moderate south-westerly wind; fine. Southern England--Fresh westerly wind; fine."

The invention of the telegraph made weather forecasts available to many people within the United States, but, of course, not on the Western Frontier. During the Civil War, the north had a regular weather-forecasting mechanism, but the south did not. And certainly, weather forecasting played a role in who won the war.

Weather. We cannot live without it, but it is sometimes difficult to live through it.

For August, I will likely turn my lens toward Seishi Yokomizo, Japan's uncontested greatest murder mystery writer, and his novel "The Honjim Murders."

Donus Roberts is a former teacher, current advisor to the ABC Book Club, an avid reader/collector of books, owner of ddrbooks, and he encourages readers to connect at ddrbooks@wat.midco.net.

This article originally appeared on Watertown Public Opinion: "Extreme Weather" reveals how nature wins wars or costs lives