Books of the month: Waterloo Sunrise to Homesickness

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Who doesn’t love Dolly Parton? As well as being a wonderful singer, songwriter and actor, she has created a remarkable legacy as a philanthropist for children’s literacy. Parton has now joined forces for a writing duet with bestselling author James Patterson. They have co-authored Run, Rose, Run (Century), a thriller about a young aspiring country music singer called AnnieLee Keyes. I really did want it to be good but, alas, it’s a pedestrian pot-boiler that features only flashes of the singer’s wit and which bears all the hallmarks of churn merchant Patterson. Parton remains in fine fettle in her nine-to-five job, however, as she demonstrates in the companion album to the book.

For fiction fans, happily, March is bursting with better new releases, especially historical ones. Among the novels I would recommend in this genre are James Runcie’s The Great Passion (Bloomsbury), set in Leipzig in 1727 and based around the life of Johann Sebastian Bach. Runcie, author of the Grantchester mysteries, has a gift for capturing the past. Karen Joy Fowler’s impressive epic Booth (Serpent’s Tail) is based around the six Booth siblings, one of whom went on to change the course of history by shooting Abraham Lincoln. Lucy Caldwell’s These Days (Faber) is an atmospheric tale set during the Belfast Blitz of 1941.

Now 80, Anne Tyler is still writing sharp chronicles of everyday domestic life, the subject of her 24th novel French Braid, which covers the Garrett family from 1959 up to pandemic times. As ever with Tyler, all of family life is there, from adultery to hip replacement. It is not on a par with her finest novels, such as Breathing Lessons, but there are moments to savor. If you are looking for something more modern, Daisy Buchanan’s Careering (Sphere) is a witty tale of the toxic world of modern work.

“In practically every high-skill profession, decline sets in sometime between one’s late thirties and early fifties,” states social scientist Arthur C Brooks in From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life (Green Tree). A cast of “strivers, overachievers and success addicts” are the subject – and target – of this strangely entertaining self-help book. It did make me wonder how much mileage there is in a happiness strategy for the “disappointed middle-aged”, especially those of us sympathetic to the Homer Simpson philosophy of: “You tried your best and you failed miserably. The lesson is, never try.”

In Hope and Fear: Modern Myths, Conspiracy Theories and Pseudo-History (Reaktion Books), Ronald H Fritz takes the reader on an enlightening tour of the sort of minds that latch on to what he calls “malign forms of junk knowledge”. The book traces a common link among fans of freaky fantasies, one that stretches from the Nazi cult of the supernatural, through alien-abduction conspiracists and up to the Covid deniers and QAnon embracers of our own mottled age.

The prodigious research that went into Daisy Dunn’s Not Far from Brideshead: Oxford Between the Wars (Weidenfeld and Nicolson) is obvious in the detailed, elegantly told story of a city in transition after the horrors of the First World War. Dunn, a leading female historian, focuses on the world of classical scholarship and offers a vivid portrait of a place of privilege and pranks. The sexism of a pre-MeToo era is clear, too. When Iris Murdoch studied at Oxford in 1938, she was warned about leading scholar Eduard Fraenkel and his “wandering hand”. “I expect he’ll paw you a bit,” advised Murdoch’s college tutor, Isobel Henderson, “but never mind.”

Novels by Andrew Miller and Kasim Ali, short stories by Colin Barrett and non-fiction by Rebecca Lee, John Davis and Jason Cowley are reviewed in full below.

The Slowworm’s Song by Andrew Miller â â â â â

Step Four of the 12-Step programme of Alcoholics Anonymous requires addicts to “make a searching and fearless moral inventory” of themselves. This fearsomely demanding task is what 51-year-old ex-soldier and recovering alcoholic Stephen Rose undertakes in the course of the novel. The trigger for this is the summons he receives to attend an inquiry into an incident 30 years previously, during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. At the time, he was a 21-year-old lost in a chaotic unknown.

Andrew Miller’s novel tells the haunting story of this complex man, now living quietly in Somerset, who at the time is trying to form a bond with his long-estranged daughter Maggie. He has, he says, opened “the dangerous book of family”. Miller, acclaimed for his previous novels such as Oxygen, shows us the complexities of a sick man trying to make sense of having lived through a horror show and battling with the long-term consequences. The portrait of alcohol addiction is subtle and moving.

The Slowworm’s Song is a stunning work of fiction, a beautifully written tale of conflict and family fracture. Miller’s book is full of small, inventive descriptions – Stephen takes in the beauty of a thicket of dahlias “bright as bandsmen”; he struggles after another bout of sleeplessness, “a night without a shore” – and has countless shards of penetrating wisdom.

The supporting characters – Rose’s former wife Evie, Maggie and her partner Lorna, the funeral director Annie Fuller, the fellow drunks and their determined counsellors – all add something vital to the story of a complex, despairing protagonist.

It’s hard not to become completely immersed in Stephen’s struggle to confront his past as a squaddie. Although the portrait of the conflict in Belfast is intense, and full of disturbing details, Miller never gets bogged down in sectarian politics. The novel walks deftly across the high wire of blame, remaining a riveting human drama, even as the tragic violence unfolds.

There is a sharp, sardonic humour running through the book. When Stephen returns to modern-day Belfast, he is gobsmacked by the changes to the city. He wonders whether the “old crew” are now “hit men with cataracts, bomb-makers with Alzheimer’s”. He also admits to himself that there is no doubt that a lot of the carnage was fuelled by alcohol, people doing things “they wouldn’t or couldn’t if they’d been sober”.

This is a deeply etched portrayal of what happens when life feels fragile, and what it is like for any of us to fear that we “have nothing under our feet, nothing that can be depended on”. Can life sometimes be unfixable? The potent ending leaves the reader to decide that answer for themselves. The Slowworm’s Song is a sublime reminder of how a great novel can have such a deep impact.

The Slowworm’s Song by Andrew Miller is published by Sceptre on 3 March, £18.99

Good Intentions by Kasim Ali â â â â â

Just after a family gathering to watch the New Year’s Eve fireworks on television, Nur, a young British-Pakistani man, decides to tell his conservative Muslim family the explosive secret of his four-year relationship with a fellow student. The problem is that Yasmina is not Pakistani, she is Sudanese. She is black.

Nur’s younger brother knows just how shocking this revelation is to their parents, Mahmoud and Hina. “You know how everyone gets about this stuff. Pakistani, Muslim, preferably known to the family or, even better, part of the family. That’s how it goes… How many people in the family do we know who are married to black people?” he warns his brother.

Deftly, in a dialogue-heavy narrative that switches in time throughout from late 2014 to early 2019, debut novelist Kasim Ali, an editor at Penguin Random House, pieces together the story of a troubled love affair and the complexities of second-generation immigrant feelings of duty, family obligation and sacrifice.

I would imagine that most fans of the book will side hugely with the bold Yasmina rather than the unlikeable Nur. Nevertheless, the sensitive story of a failing romance offers a clever vehicle for an unflinching depiction of South Asian anti-black prejudice and the conflicting pressures of family and culture. The scene in which Yasmina finally confronts her lover about his own complicity is particularly powerful.

There are no easy answers on offer in Good Intentions but the questions about race, relationships and mental health are absorbing.

Good Intentions by Kasim Ali is published by 4th Estate on 3 March, £14.99

Waterloo Sunrise: London from the Sixties to Thatcher by John Davis â â â â â

Some of the forgotten town-planning schemes for London make eye-catching reading in Waterloo Sunrise: London from the Sixties to Thatcher. The most bizarre were the failed 1968 scheme to turn Piccadilly Circus into “Piazzadilly”, with Eros relocated to a raised pedestrian square and traffic channelled underneath; and the 1973 Docklands redevelopment model that proposed golf courses, three equestrian centres and a safari park.

John Davis, emeritus fellow in modern history at The Queen’s College, University of Oxford, takes a multifaceted look at London, including how the city led the UK fashion boom in the 1960s and how the development of the capital’s cuisine reflected the nature of London itself. As well as a memorable portrait of seedy Soho, he also investigates how large parts of London’s working-class character were destroyed in the interests of private capital. London remains a city of haves and have-nots and there is a sobering chapter on the extent and severity of the East End’s economic collapse and how this period shaped 21st-century realities.

The interesting social history in the book captures the world of London in the 1970s (a place and time in which I grew up), of Wimpy Bars, Pizzaland, the famous York Way Butchers G W Biggs – which provided the meat for all the leading burger restaurants in London – and the regular sight of wannabe London cabbies doing their “Knowledge” research on moped missions.

The chapter on “The London Cabbie and Essex Man” is especially revealing, noting that drivers shared a belief that “Bermondsey tips better than Belgravia”. Although the cabbies were predominantly Jewish (5,000 of the 13,000 drivers in 1971, The Jewish Chronicle estimated), black taxi work was also the domain of a group of Cossack refugees from the Bolshevik revolution. That unusual revelation reflects one of the many terrific things about London: it is a truly multicultural city. That said, Davis’s chapters on racism are shocking. London’s police come out of the book badly. “One inspector remembered being shown how to ‘fit up’ blacks on his arrival at Harrow Road police station in 1968,” he writes. Not a single one of the 41 complaints of racial discrimination against the Met was upheld in 1969, the same year that Woolworth’s in London believed it was acceptable to issue rules that it “under no circumstances will allow… immigrant girls to serve loose biscuits”.

As well as the crisp storytelling, Waterloo Sunrise also contains dozens of atmospheric photographs, along with graphs and tables that highlight the history of London and how it changed in the run-up to Thatcher’s Britain. There are gaps in the book – there could have been more on sport, parks and schools in the capital – but, overall, this is an engrossing, scholarly account of a time when London was in transformation (the 100-plus pages of notes and bibliography are a sign of the thorough research) and one that will interest Londoners and non-Londoners alike.

Waterloo Sunrise: London from the Sixties to Thatcher by John Davis is published by Princeton University Press on 8 March, £30

Homesickness by Colin Barrett â â â â â

Strangely, I read The Alps, one of eight short stories in Colin Barrett’s enjoyable collection Homesickness, on the day that news broke about the appalling cat-kicking antics of West Ham defender Kurt Zouma. Cat abuse is one of the plot lines in The Alps, a story set in a rural Irish bar. The perpetrator of this cat attack has sought refuge and soon begins boasting about his prowess with a replica Japanese sword (a katana).

One of the delights of this particular story – and indeed further excellent Barrett tales such as The Ways, about three siblings struggling to cope after the death of their mother – is the vivid cast of misfits and outcasts that Barrett, from County Mayo, brings to life. The Alps brothers, Eustace, Rory and Bimbo, “were shortish men with massive arses and brutally capable forearms”, writes Barrett. Those forearms and big arses come into play when violence breaks out in the bar. Looking on are another set of local grotesques, including Peader Ginty, who sits drinking while a nose cannula feeds him oxygen out of a tank nestling in his trolley bag. “His face was bloated and yellow, the corners of his eyes sudsy with discharge… he was by this stage of things a big watery bag of imperilled organs,” writes Barrett with cold-eyed wit.

Another triumph is the opening story A Shooting in Rathreedane, about a policewoman forced to deal with local criminal lowlife after a shooting at a farm. The minutiae and memory of small-town life is also the subject of The Silver Coast, set around a funeral reception.

Homesickness is an adroit, wry set of stories by an author who has an eye for the quirks of human nature.

Homesickness by Colin Barrett is published by Jonathan Cape on 10 March, £12.99

How Words Get Good: The Story of Making a Book by Rebecca Lee â â â ââ

There are many enjoyable digressions in How Words Get Good: The Story of Making a Book, including a small quiz about the original titles of books. Did you know a contender for Peter Benchley’s Jaws was his father’s tongue-in-cheek suggestion: What’s That Noshin’ on My Leg?. While that title is arguably an amusing improvement on Jaws, I’m not sure anyone can seriously argue that Blanche’s Chair in the Moon was better than Tennessee Williams’s final title, A Streetcar Named Desire.

Rebecca Lee, an editorial manager at Penguin Random House, is an engaging guide to the behind-the-scenes work involved in getting a book published, not least because of her candid admissions about the cock-ups that are an inevitable part of the process. “Have I had an author email me (very politely, under the circumstances) to point out I’d misspelt their name on the title page of their proofs? Mea culpa. Have I been part of a team that managed to print 20,000 copies of The Importance of Being Ernest? Speaking earnestly, I absolutely have,” she admits.

Lee offers an insightful guide to the professional strands of publishing, from the authors – including the “literary factory farming” that is now part of the industry – to the ghost-writers, agents, translators, editors and copy-editors who try to knock a book into the best possible shape. She also offers her thoughts on the stylistic practicalities involved in book publishing, including footnotes, indexes, blurb writers, fact checkers, cover designers, text designers and printing factories.

Lee explains the minutiae of editing and offers lots of quirky digressions, especially in the chapters about spelling and ‘Specks in your text: Grammar and punctuation’. All natural pedants will also appreciate her pernickety approach to ‘minor matters’, such as the spacing of ellipses and the preference for smart quote marks (“ ”) over the straight ones known as dumb quote marks (" ").

How Words Get Good: The Story of Making a Book by Rebecca Lee is published by Profile Books on 17 March £14.99

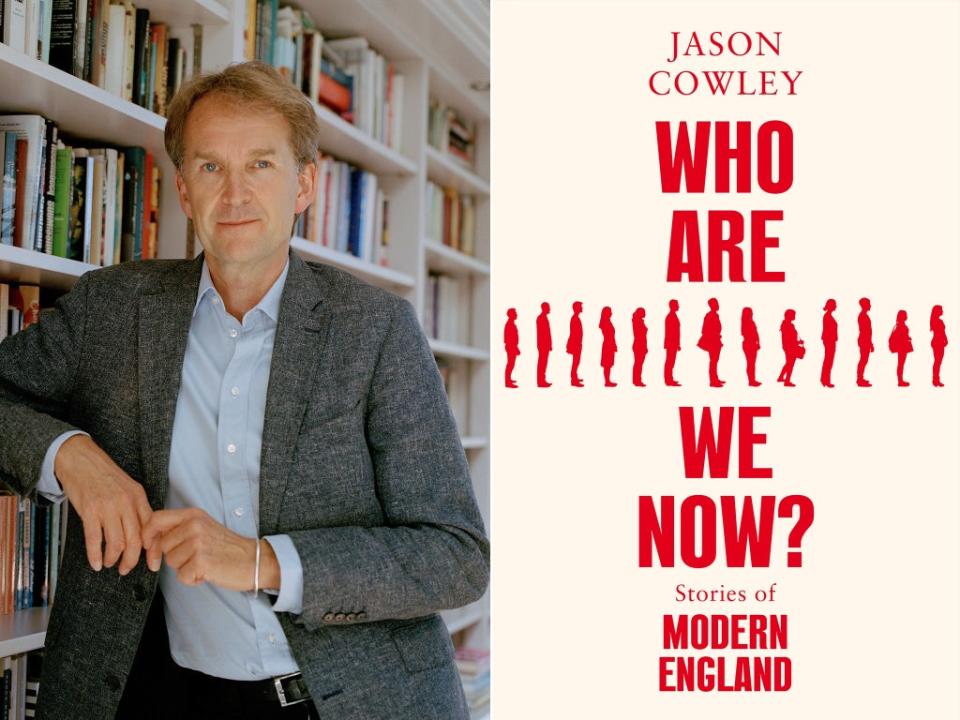

Who Are We Now? Stories of Modern England by Jason Cowley â â â â â

Jason Cowley’s Who Are We Now? Stories of Modern England asks a deceptively simple question: “Who are we now, after Brexit, after the pandemic, as a pro-independence majority in the Holyrood parliament marshal their forces in Scotland and the United Kingdom faces the threat of dissolution?”

The author, born in 1965 and who has lived in England all his life, uses a series of resonating news stories – including the Chinese cockle-pickers who died on the sands of Morecambe Bay in 2004; a pensioner campaigning against the closure of her GP surgery; the repatriation of soldiers at Wootton Bassett; Gillian Duffy and that fraught “bigoted woman” confrontation with Gordon Brown during the 2010 general election; and the courage of Mohammed Mahmoud in defending far-right terrorist Darren Osborne during an attack on Finsbury Park Mosque worshippers – to examine this era of fragmentation.

Cowley, a compassionate observer, is good at examining the root causes of some of these events. In the case of the Chinese cockle-pickers, for example, he reflects on the damage done by governing elites (from both main political parties) turning away from dealing with the exploitation of people by traffickers.

Perhaps the most poignant chapter is the one looking at Harlow in the light of Brexit, the event “realigning British politics”. He looks at this seismic political event through the lens of the death of Polish immigrant Arkadiusz Jozwik, after being punched by a local youth in this now “shabby and neglected” town. “The story of my hometown is also the story in microcosm of England since the end of the Second World War – of what the English revolution got right and what it got wrong,” Cowley writes.

Overall, the book is strong at establishing interesting context, and full of thoughtful analysis, alongside salient asides. His character summaries are spiky, too. Of David Cameron, for example, Cowley remarks on “how detached this smoothly insouciant, risk-taking, self-confident charmer was from the realities of most people’s everyday lives”. After describing Boris Johnson as a “chancer” in the opening chapter, Cowley later lauds the prime minister’s speech praising the NHS for saving his life from Covid. “I’d never heard him speak as he did that day – so authentically from the heart, with such power and emotional truth”, Cowley writes. This seems a very generous tribute to a compulsive liar, and was obviously written before allegations emerged that Johnson was downing beer in Downing Street parties while NHS workers slogged to save lives.

For those of us who fear that England remains anchored in its past, Cowley offers the assertion that “a persistent sense that something is missing – or has been lost or taken away from the English – flows like an underground stream through the centuries”. Fabio Capello, the Italian who managed the English football team from 2007 to 2012, echoed this view, once describing the 1966 World Cup victory as the “returning ghost” of the national team. Although there are plenty of downbeat reflections in Cowley’s book, he does see grounds for optimism; not least in the shape of current England football manager Gareth Southgate. “Under the leadership of Southgate, the England team has become a symbol of national unity,” he writes.

Who Are We Now? Stories of Modern England by Jason Cowley is published by Picador on 31 March, £20