How Boris Johnson draws on the past to rule in the present – with a little help from myth

Those struggling to understand how Boris Johnson helped win the 2016 Brexit referendum before becoming prime minister should consider how myth functions in politics.

Throughout his career, Johnson has deployed a type of myth referred to by the philosopher Hans Blumenberg as “prefiguration”: relating emotionally charged events from a country’s past to issues in its present.

Blumenberg was born in 1920 to a Catholic father and a German Jewish mother. Because of this background, he was banned by the Nazis from studying at German universities. After the war, despite this persecution, he became one of Germany’s most prominent philosophers.

In 1979, Blumenberg published a book entitled Work on Myth, in which he claims that myths provide humans with a way of coping with anxieties arising from their environments. Confronted by threats such as thunder and lightning, for example, humans gave these forces names and personalities, making them familiar and approachable.

Myth is seen by Blumenberg as helping humans to orient themselves in threatening surroundings. It is not the opposite of reason, as many thinkers of the Enlightenment argued, but serves the pragmatic function of making humans feel at home in the world. It therefore needs to be taken seriously.

The stories we tell

When Blumenberg’s book appeared in 1979, some reviewers saw it as offering a curiously positive view of myth, which allegedly failed to examine the role played by myth in Nazi politics.

But in 2012, I discovered a letter to Blumenberg written by one of those reviewers. In reply, Blumenberg mentioned that Work on Myth was “missing a chapter that was already present in the manuscript, but which completely and utterly spoiled my taste for the book. I held it back. After I am gone, one may do with it what one wants.”

I found that missing chapter, entitled “Prefiguration”, in the German Literary Archive. Its publication in German in 2014, co-edited by Felix Heidenreich and me, revealed Blumenberg to be a theorist who helps us to understand political myth, and I also analysed these ideas in my recent book on Blumenberg.

As the literary critic Erich Auerbach shows in his essay Figura, the term prefiguration comes from Biblical scholarship, and refers to how events or characters in the Old Testament may prefigure those in the New. In 1 Corinthians 15:22, for example, Adam in the Old Testament is seen to prefigure Christ in the New. When seen in retrospect, the first figure seems to anticipate and legitimise the second.

Read more: Soft Brexit is more likely than ever, thanks to Boris Johnson’s new hardline cabinet – here's why

On a more basic level, prefiguration aids orientation by providing a precedent from the past that seems to reduce the complexity of the present. One of Blumenberg’s examples comes from the Yom Kippur War of 1973. When deciding when to invade Israel, the Egyptian and Syrian armies are said to have chosen the tenth day of Ramadan, not only because it coincided with the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, but also due to Muhammad having begun his preparations for the Battle of Badr on this day in the year 624. Here prefiguration invokes a mythic sense of repetition: the date of an important battle in the history of Islam was seen as auspicious.

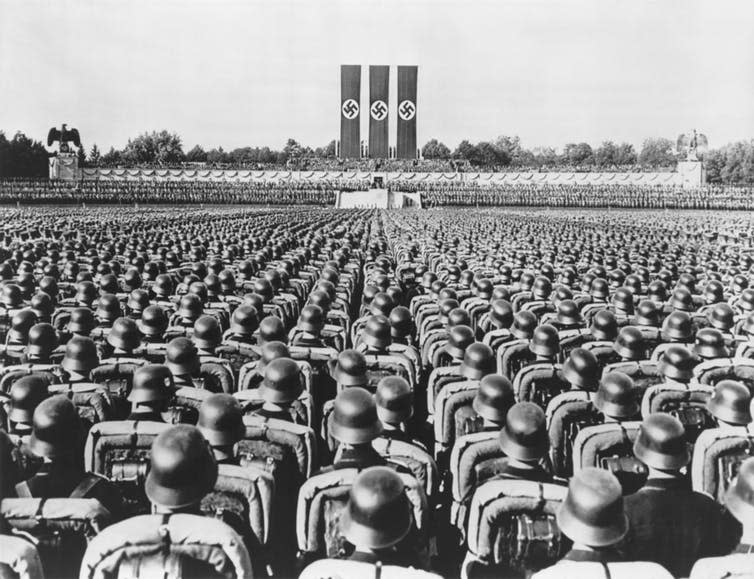

For Blumenberg, prefiguration lends mythical legitimacy to decisions that lack rational justification. Hitler’s ruinous comparisons between himself and figures such as Frederick the Great and Napoleon are the central case study used by Blumenberg to illustrate this theory.

How Boris deploys it

Johnson understands prefiguration. He knows the most significant episode in recent British history is victory over Germany in World War II, and that its “sacred” protagonist is Winston Churchill. Johnson’s Churchill biography of 2014 is a study in prefiguration, in which he presents himself as the heir to Churchill’s legacy. In it, Johnson wrote that among Churchill’s many sayings “a text will be found to … validate some course of action – and that text will be brandished in a semi-religious way, as though the project had been posthumously hallowed by Churchill the sage and wartime leader.”

During the Brexit campaign, Johnson made precisely this rhetorical move. The European Union, he wrote in the Telegraph newspaper in May 2016, is an attempt to create a European superstate “just as Hitler did”. By contrast, Churchill’s “vision for Britain was not subsumed within a European superstate”.

These irresponsible comparisons between the EU and Nazi Germany were criticised at the time, even by some of Johnson’s fellow Tories. But the message cut through. Rational arguments for remaining in the EU were trounced by the campaign to “Take Back Control”. When combined with Johnson’s references to Churchill and World War II, this slogan allowed Leave to command the emotional terrain of political myth, reminding voters of their nation’s heyday, when the British Empire was still intact.

Read more: Three issues Boris Johnson's new government must tackle – none of which is Brexit

The mastermind of that campaign, Dominic Cummings, is now leading the team in 10 Downing Street. As a potential election looms, this raises troubling questions for Johnson’s opponents. Is rational argument enough to defeat political myth? Or must Remain also come up with a captivating myth to communicate the rational grounds for staying in the EU if that is to ever happen? Are rationality and myth even compatible?

Considering these problems requires an appreciation of the rhetorical power of political myth, and in this Blumenberg can help us.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Angus Nicholls's research on Hans Blumenberg was funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Germany. He is a member of the Labour Party.