Born with a treatable condition at a Milwaukee hospital, she died 30 hours later. What happened to Baby Amillianna?

On Sept. 18, 2021, Amillianna Ramirez-Johnson was born at Ascension Columbia St. Mary’s hospital in Milwaukee. She weighed 6 pounds, 15 ounces, had a halo of fuzzy, dark curls, 10 fingers, 10 toes and a healthy heart.

But her weak cry and the pale-blue tint to her skin signaled her breathing was stressed. The umbilical cord was “stained green,” according to medical records.

The staining was from meconium, a thick, tar-like substance that when passed by a newborn — creating the baby’s first dirty diaper — is a sign of good health. But when a fetus is stressed, meconium is released too soon, creating a toxic mix of amniotic fluid and waste that is inhaled prior to birth.

Amillianna had inhaled the sticky substance either in utero or while traveling through the birth canal. It entered her airways and settled in her lungs.

An hour after she was born, Amillianna was transferred to Room 624 in the neonatal intensive care unit. Before she and her parents were separated, a nurse held Amillianna close to her mother Karen Ramirez's cheek, the newborn's lips resting there for a quick couple of seconds.

"The nurses said they had to clear her lungs,” Ramirez said. “She never got to go on my chest like my other kids did.”

While inhaling some meconium is easily treated by suctioning it out from the newborn’s airways immediately after birth, inhaling too much causes meconium aspiration syndrome — which can result in a condition known as persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, affecting a baby’s ability to breathe and circulate blood.

The condition affects 2 out of every 1,000 live births. Treatment has evolved to the point that roughly 90% of newborns, when given proper treatment, survive, according to studies published in the National Library of Medicine.

Amillianna's parents hoped she would be among the percentage of newborns who survive the condition.

But it would prove deadly.

Born at 5:43 a.m., she was pronounced dead at 11:43 a.m. the following day, exactly 30 hours later.

A review of medical records by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and medical experts suggests Ascension Columbia St. Mary's didn't provide Amillianna with the widely accepted standard of care for a baby with persistent pulmonary hypertension caused by meconium aspiration and did not transfer her to a more specialized hospital when it became apparent their treatment wasn’t working.

"Amillianna was not suffering from an incurable disease. Medicine has evolved. It has the knowledge and the tools to treat her condition," said Nicholas Szokoly, an attorney based in Baltimore, Maryland, who represents patients and health care systems in medical malpractice cases.

His assessments of Amillianna’s care are based on the opinions of a consulting physician who reviewed Amillianna's and Ramirez's records at Szokoly's request. The consulting physician, a board-certified pediatric critical care doctor with more than 20 years of experience, has testified as a medical expert for the firm on behalf of plaintiffs and defendants.

"It's like that hospital is practicing medicine from the 1980s," Szokoly said.

Szokoly's firm explored taking the family's case, but decided against it because of Wisconsin's low $500,000 cap for medical malpractice cases in the death of a minor. However, the medical expert the firm used believed there was “medical negligence" in Ascension's failure to transfer Amillianna and that "basic standards of care" were not met for a baby with her condition.

The Journal Sentinel provided the hospital with a list of questions about the case in mid-January, but officials initially refused to offer more than a general statement citing patient privacy. After the Journal Sentinel sought and obtained signed permission from Amillianna's father, Justin Johnson, for the hospital to discuss her care, the hospital issued a new statement Wednesday evening.

That statement did not directly address any of the questions, other than to say broadly that its "thorough internal review found the standard of care provided to this patient was met by the clinical team."

"The loss of any child is tragic and our hearts and prayers go out to this family," an Ascension Wisconsin spokesperson said in the statement.

Every year, roughly 100 babies die in Milwaukee before celebrating their first birthdays, a measure of infant mortality that is one of the worst in the country. In 2021, Amillianna was among them.

Her parents believe her short life illustrates what experts and studies have said for years: Many infant deaths are preventable. And a disproportionate number of the babies affected are Hispanic, Black and Native American. Amillianna was all three.

“I blame them for her death,” said Ramirez. “They could have done better, they could have done more for her. Everybody else’s babies got to go home except for mine.”

Before birth

Ramirez, 42, was born in Hillsboro, a town of about 1,000 people roughly an hour southeast of La Crosse and the Minnesota border. She speaks Spanish and English, with hints of her Spanish dialect punctuating words when she speaks in English. Her family moved to Milwaukee when she was little.

She connected with Amillianna's father on social media. He was born in the small town of Warren, Arkansas, and also moved to Milwaukee at a young age.

On July 18, 2020, she sent a message to Johnson, a Facebook friend, for his 33rd birthday. The message sparked more messages and conversations, and they soon moved in together. When they learned she was pregnant with a baby girl, Johnson suggested calling her Amillianna, a name he had come up with when he was 13 years old and a huge fan of R&B singer Aaliyah's song "One in a Million."

"I had waited so long to give somebody that name," said Johnson, who has a 6-year-old son from a previous relationship. "I was finally having a daughter."

Ramirez liked the name, too, and was eager for the arrival of her fourth child and second daughter. She started putting together a wardrobe of shoes, dresses and onesies for Amillianna.

She was scheduled to be induced Sept. 18, three days after her due date. Painful contractions pushed Ramirez and Johnson to the hospital a few hours earlier than scheduled.

“I thought I was going to have her in the car,” Ramirez said.

By 4:17 a.m., at the hospital, a fetal heart monitor was strapped like a belt around her belly.

Despite Ramirez's documented risk factors — including "advanced maternal age (40) and risk of stillbirth," low iron levels and occasional tobacco use — from the time she was admitted to the time of birth, she did not receive uninterrupted fetal monitoring that would have provided real-time information on Amillianna’s status.

The longest period of uninterrupted fetal heart rate tracing was two minutes, according to the records. Ten minutes is the minimum required for accurate assessment, according to the Association of Women's Health, Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses.

And that trace appears to have been misread, said Erin Murders, an educational instructor for the association. Since beginning her career in 2005 Murders has held multiple clinical, educational and leadership roles within the maternal infant setting.

Hospital staff who reviewed the trace should have seen that Amillianna wasn't getting enough oxygen and taken steps to improve that, or consulted with a physician to expedite her delivery, Murders said. Nothing in the records indicates that happened.

When Amillianna was born, her condition confirmed what fetal heart rate tracing is meant to detect: respiratory distress.

Within an hour, she would be transferred to the NICU.

The doctor admitting Amillianna to the NICU cited respiratory distress, “likely meconium aspiration syndrome,” probable persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn and the need to rule out sepsis, according to medical records.

One hour after birth

For decades, the standard of care for a newborn with persistent pulmonary hypertension, like Amillianna, has included providing inhaled nitric oxide and connecting the baby to high-flow oscillatory ventilation, according to a 2023 study published in the National Library of Medicine. Both are basic, nonsurgical, low-risk treatments administered by a respiratory therapist with a doctor's order.

Ascension doctors had access to both, but neither was immediately provided to Amillianna.

Instead, upon her arrival to the NICU, Amillianna was intubated, placed on a regular ventilator, given two broad spectrum antibiotics for a possible infection, given a liquidy substance known as surfactant to prevent her lungs from collapsing and placed on a feeding tube.

All those treatments are recommended for newborns in respiratory distress. But it would be another 21 hours before Amillianna would receive inhaled nitric oxide and high-flow ventilation.

Tina Pennington, a nurse with 28 years' experience — 18 as a NICU clinical expert with the high-risk pregnancy program at University of Arkansas Medical Sciences — reviewed Amillianna's medical records at the Journal Sentinel's request.

She said when she cares for newborns in critical respiratory distress, her general practice includes keeping a close eye on their condition by checking their blood gases — a vital indication of how a newborn's respiratory and metabolic conditions are faring — "every 1 to 3 hours."

"Persistent pulmonary hypertension is a complex, critical disease," Pennington said. "Any delay in treatment can quickly lead to acute failure in a newborn's body systems and death can follow."

Amillianna's doctors ordered her blood gases be drawn every three to six hours. The hospital declined to comment on whether the doctor's order was sufficient for a newborn with Amillianna's diagnosis.

However, Dr. Chintan Desai, Ascension Wisconsin's chief medical officer, said in an emailed statement Tuesday to the Journal Sentinel that "many factors influence medical decision-making."

"It's important to recognize that the standard of care could be met by various methods of treatment and that one method is not inherently superior to another, as patients may have varying responses to identical treatments," Desai's statement said. "The application of guidelines should be tailored to the specific clinical situation."

Amillianna's blood gases were drawn around 7 a.m. and 10:20 a.m. Then there was an eight-hour gap before they were drawn again at 6:30 p.m. and 9:30 p.m., the records show.

One metric obtained in the blood gases is the body's pH (potential hydrogen) level, a key indicator of whether cells will function properly. At 9:30 p.m., Amillianna's pH level was 7.52, higher than the normal range of 7.26 to 7.49.

“I don’t like the 9:30 gases at all,” Pennington said. “They are over-ventilating this baby.”

Pennington said at this point, Amillianna’s medical team should have corrected the ventilator settings and the amount of oxygen she was receiving to try to maintain appropriate levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide in her blood.

But if corrections were made to the ventilator settings or the amount of oxygen Amillianna was receiving, none of those numbers were added to her chart.

When an infant breathes in too much meconium and develops persistent pulmonary hypertension, one option is to place the baby on a short-term life support system called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO.

Mechanical ventilation devices, like the one Amillianna was connected to, can move only air. In contrast, ECMO adds oxygen to and removes carbon dioxide directly from a patient's blood — basically functioning as the patient's lungs, only outside their body.

ECMO is designed to give patients' lungs a break, allowing the meconium to dissolve on its own and providing a better chance to recover.

Depending on the amount of meconium inhaled, this could take hours to days, said John Van Cleave, a medical professional who specializes in the system for neonatal and pediatric patients.

Van Cleave agreed to talk to the Journal Sentinel specifically on how ECMO works, when it is commonly used, and the risks and benefits of the technology. He did not review Amillianna’s medical records.

“If the meconium is causing the persistent pulmonary hypertension, time on ECMO would clear up both,” Van Cleave said.

Van Cleave stressed the life-support system is associated with a lot of risks. The main risks are bleeding from the incision sites, a stroke from a blood clot or an air embolism developing and lodging in the brain.

“No one is going to receive ECMO that would not otherwise die without it,” Van Cleave said.

According to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, 393 newborns diagnosed with persistent pulmonary hypertension were put on ECMO from 2016 to 2020 worldwide for an average of seven days. Of the 393 newborns, 73%, or 288, survived.

During that same timeframe, there were 611 newborns with meconium aspiration syndrome put on ECMO. On average, the newborns were on the device for six days, with 599, or 91%, of them surviving.

Columbia St. Mary’s does not have ECMO capabilities. But seven other Wisconsin hospitals do — including Children’s Wisconsin, 10 miles away.

Ascension Wisconsin declined to comment when asked if it has a protocol to determine which patients should be transferred to a higher level of care.

Based on Amillianna’s 9:30 p.m. blood gases, “I probably would be thinking about transferring her right about now,” Pennington said.

Instead, all appeared normal in Room 624. Johnson and Ramirez returned to the room so she could shower and rest.

21 hours after birth

That changed around 3 a.m. when panic spread like a wave through the NICU.

It hit Ramirez, too.

“Something just woke me up. The next thing I know, nurses are coming into my room telling me I need to come with them, and Amillianna is not looking so good.”

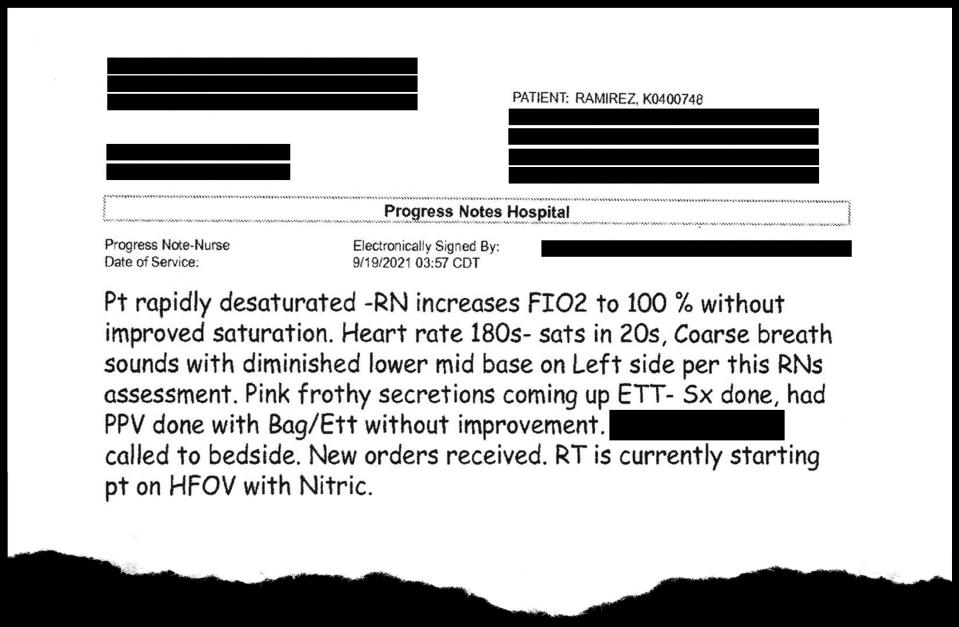

A nurse’s progress note electronically signed at 3:57 a.m. and uncharacteristically typed all in bold and large font size, details Amillianna’s deteriorating health.

The patient rapidly desaturated. Oxygen increased to 100% without improvement. Coarse breath sounds. Pink frothy secretions coming up the endotracheal tube.

Dr. called to bedside.

New orders received. Respiratory therapist is currently starting patient on HFOV with Nitric.

At that point, 21 hours after she was admitted to the NICU and 24 hours after she was born, Amillianna is started on the two standards of care — high-frequency oscillatory ventilation and inhaled nitric oxide — that she should have received immediately, according to Pennington and the law firm’s medical expert.

A final blood gas was taken at 4:59 a.m. on Sept. 19. The values show Amillianna's respiratory system was shutting down and not enough oxygen was reaching her body tissue. This prompted her body to produce lactic acid and then convert the excess acid to glucose, accounting for a spike in her blood sugar.

Several key readings, including the normal ranges used by the hospital and included on the medical records:

Blood sugar (glucose) had spiked to 408 mg/dL. The normal range is 30 to 90 mg/dL.

Carbon dioxide level in the blood was 98 mmHg. Normal range is 27 to 40 mmHg.

Bicarbonate level in the blood was 14 mmol/L. Normal range is 17 to 24.

pH level is 6.76. Normal range is 7.26 to 7.49.

"A pH level less than 7 is basically considered incompatible with life," Pennington said. "At this point, she is near death."

A doctor was called to Amillianna’s bedside sometime after 3 a.m. Before her shift ended around 7 a.m., she would call Children’s Wisconsin twice to ask about transferring Amillianna to be put on ECMO, the short-term life support. It was the first time transferring Amillianna was discussed, according to medical records.

The Ascension doctor was asked by a Children’s cardiologist and confirmed Amillianna’s heart was normal and healthy.

There are no additional details of the conversations between doctors at the two hospitals in the medical records.

A different doctor later wrote in notes that Amillianna was “too unstable to attempt transport to Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin for ECMO, despite attempts to maximize medical support.”

Her parents were told “she was unlikely to survive.” A baptismal-like white cap and gown were laid on Amillianna and a relative of Johnson's, who attends Jesus is the Way Church of God, called Sister Veronica Stanton, who arrived to bless her.

It was around this time Ramirez and Johnson had their first opportunity to hold their daughter. She was placed in their arms while still connected to the ventilator, the vibrations from the breathing machine shaking her tiny body, a web of tubing forcing them to keep space between them.

Johnson held Amillianna, gently swaying and rocking her, Ramirez capturing with a cellphone video the only time he’d hold his daughter.

“The first time I held my daughter, I believe she was already dead,” Johnson said.

When Ramirez held her daughter, she kept asking Johnson why their daughter was so cold.

“I didn’t want to tell her why I thought she was cold,” Johnson said.

Ramirez remembers being asked to withdraw Amillianna’s life support.

“Stop asking me to pull the plug on my daughter because I’m not f—ing doing it,” Ramirez remembers thinking.

At 11:43 a.m., a doctor would pronounce Amillianna dead while in her mother’s arms.

The final autopsy determined Amillianna died from bilateral meconium pneumonitis — the meconium she inhaled led to pneumonia in both her lungs — due to placental insufficiency.

“When a child goes to the NICU, they are supposed to get special care, special treatment,” Johnson said. “I don’t believe my baby did, at all.”

After death

In the hallway outside the NICU room, Johnson began asking questions of a group of nurses involved in his daughter's care.

Ramirez recalls that Johnson wasn't receiving many answers.

"He was upset. Milli had just died," Ramirez said, referring to her daughter by her nickname.

Johnson said he was told security would be called if he didn't "calm down." Mindful of not wanting to be labeled an angry Black man, he and Ramirez made their way back down to her room.

"Once they label you, that's it. They blame you, shut you down for asking basic questions," Johnson said. "All I was asking for was answers."

Johnson and Ramirez eventually had to leave their daughter. Ramirez showered and the parents packed up their belongings to go home.

They left the hospital, Amillianna's carseat empty in the back seat.

How we reported this story

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Jessica Van Egeren first began researching overworked staff and concerns surrounding patient safety at Ascension Columbia St. Mary's hospital in Milwaukee at the end of 2022. This reporting led to families stepping forward to share their own experiences.

One such experience came from Tanzanique Carrington. Her husband, Keith Carrington, died at the hospital on Aug. 22, 2023, following a surgery to amputate four of his toes. He was 48.

Carrington believed "lackadaisical care" led to his death. She was never able to find an attorney to take his case and her misconduct/complaint of care report filed with the Wisconsin Department of Health Service's Division of Quality Assurance found no violations in her husband's care. To this day, she believes his death was due to a blood clot, not septic shock.

Justin Johnson, Amillianna's father, saw the story. He contacted Carrington, a principal at a Milwaukee middle school, who put him in contact with Van Egeren. She obtained permission from Johnson and Amillianna's mother, Karen Ramirez, to access their medical records from Ascension Columbia St. Mary's hospital and Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers where Ramirez received her prenatal care.

Attorney Nicholas Szokoly with Murphy, Falcon & Murphy obtained permission from Johnson to share with Van Egeren additional medical records that he had requested from the medical centers. Szokoly's medical expert reviewed the medical records and believed Ascension Columbia St. Mary's did not follow standards of care when treating Amillianna and was medically negligent in its failure to transfer Amillianna for a higher level of care.

Szokoly also obtained permission to discuss these findings with Van Egeren. Ascension Columbia St. Mary's declined multiple opportunities to comment on Amillianna and Ramirez's care, citing state and federal privacy laws.

Van Egeren, a licensed registered nurse who previously worked as a cardiac nurse in a Madison hospital, pored over the hundreds of pages of records. She then sought out medical professionals with expertise in the areas of care relevant to Amillianna and her mother.

Finally, Amillianna's parents spent an untold number of hours detailing the loss of their daughter and what life has become since her passing. Amillianna's story is the culmination of those interviews and six months of research into her care.

The Journal Sentinel provided the hospital with a list of questions about the case in mid-January, but officials initially refused to offer more than a general statement citing patient privacy. After the Journal Sentinel sought and obtained signed permission from Amillianna's father, Justin Johnson, for the hospital to discuss her care, the hospital issued a new statement Wednesday evening.

That statement did not directly address any of the questions, other than to say broadly that its "thorough internal review found the standard of care provided to this patient was met by the clinical team."

Read part two of this story: Experts believe negligence contributed to a baby's death. Wisconsin laws don't make it worth it for anyone to take the case.

Jessica Van Egeren is the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel's enterprise health reporter. She can be reached at jvanegeren@gannett.com or 608-320-3535.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: A baby died soon after birth at Ascension Columbia St. Mary's. Why?