Born in Uzbekistan With Korean Roots, Jenia Kim Is Redefining the Notion of National Dress

j-kim-uzbekistan

Photo: Hasan KurbanbaevLike many young designers, Jenia Kim wanted to make clothes that said something about where she came from. Only in her case that story was rather complicated. Kim is one of an estimated half-million ethnic Koreans in the former Soviet Union who compose the diaspora known as the Koryo-saram. Though she now lives in Moscow, she was born in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, to ethnic Korean parents who belonged to a community that had been forcibly moved to Central Asia by Stalin in the late 1930s.

Growing up in Uzbekistan, Kim was surrounded by fellow Koreans who looked like her and who ate the same food. “I didn’t think for a second that I was different,” Kim, now age 28, says in Russian. “I had many Korean friends, and we felt like we were home, calm and comfortable. In our five-story apartment, there were more Koreans than Uzbeks. I didn’t think about where I came from or how I ended up there.”

Kim’s life dramatically changed when she moved to Moscow at age 11. “Our family was the only ‘other’ [family] in the whole community. [Russian] grandmothers would look at me like I was an alien.” She often felt ostracized and sometimes was the target of racial slurs. It was not until she entered university, where she met other young people from different cultural backgrounds, that she felt more accepted and began to explore her complex identity.

Since the inception of her label, J.Kim, in 2013, Kim has sought to tap into her roots. She’s gone as far as the South Korean island of Jeju to research the uniforms of female clam free divers. Kim’s latest design project reinterprets the national Korean dress of jeogori by using vibrant fabrics from traditional Uzbek costumes and Soviet-era materials. The collection and photographs reflect Kim’s fragmented memories of home—how she experienced her culture as a child without having any real understanding of its origin and her family’s complicated history in the Soviet Union.

j kim tashkent images

Photo: Hasan KurbanbaevWhile Kim celebrates her mixed cultural background, she now understands that this colorful heritage came at a great cost. Her ancestors were poor Korean farmers who first arrived in czarist Russia in the late 19th century. They settled in the Russian Far East in the region of Primorsky Krai, which borders North Korea and China. There Korean immigrants developed their own institutions and spoke their own dialect of Korean. Their community thrived until the 1930s, when Japan and the Soviet Union fought over disputed territories. Stalin became suspicious of the Korean community’s ties to Japan. In 1937 he herded some 180,000 ethnic Koreans in cattle cars and deported them to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan during the Siberian winter. (Koreans were among many ethnic groups in the Soviet Union, including the Crimean Tatars, who were subject to forced migrations during this time.)

jkim-tashkent

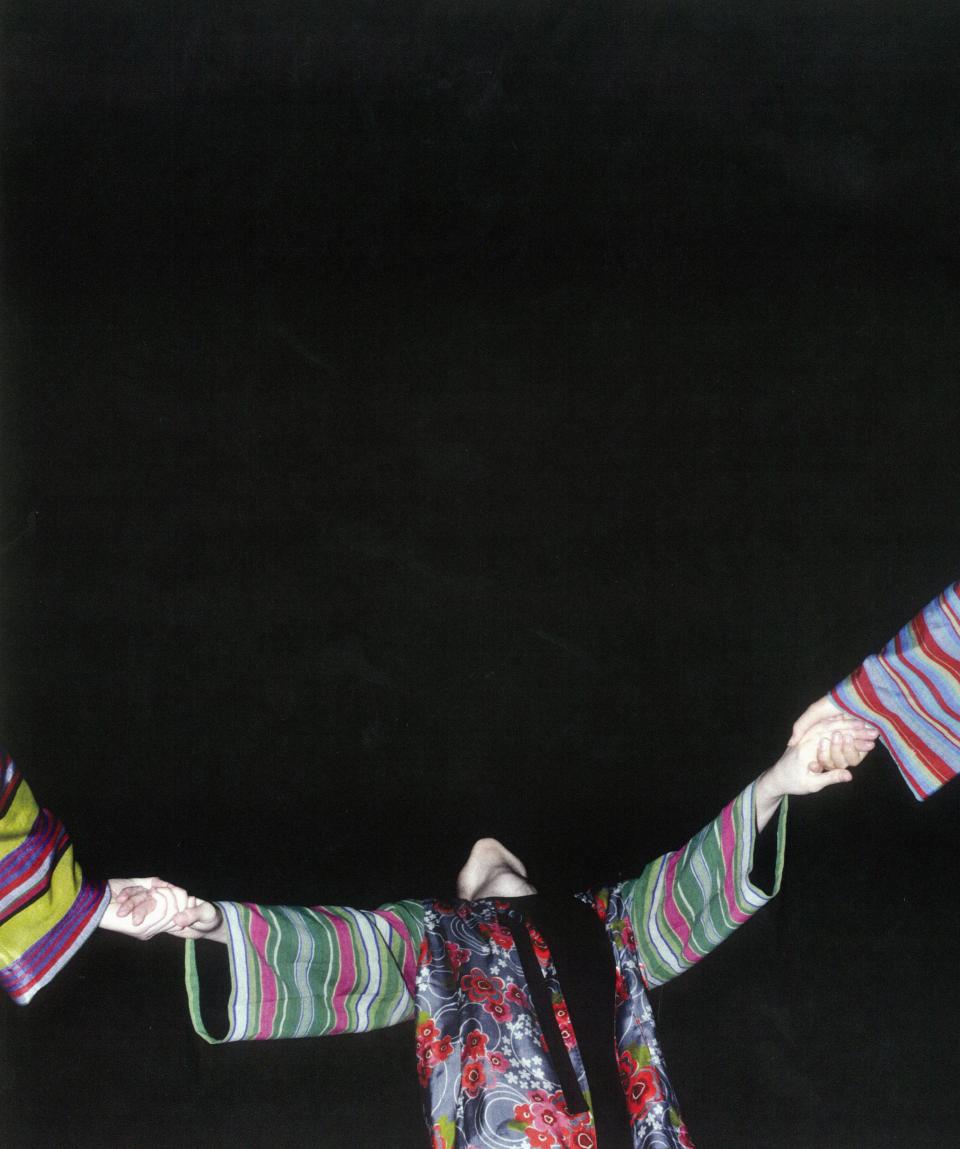

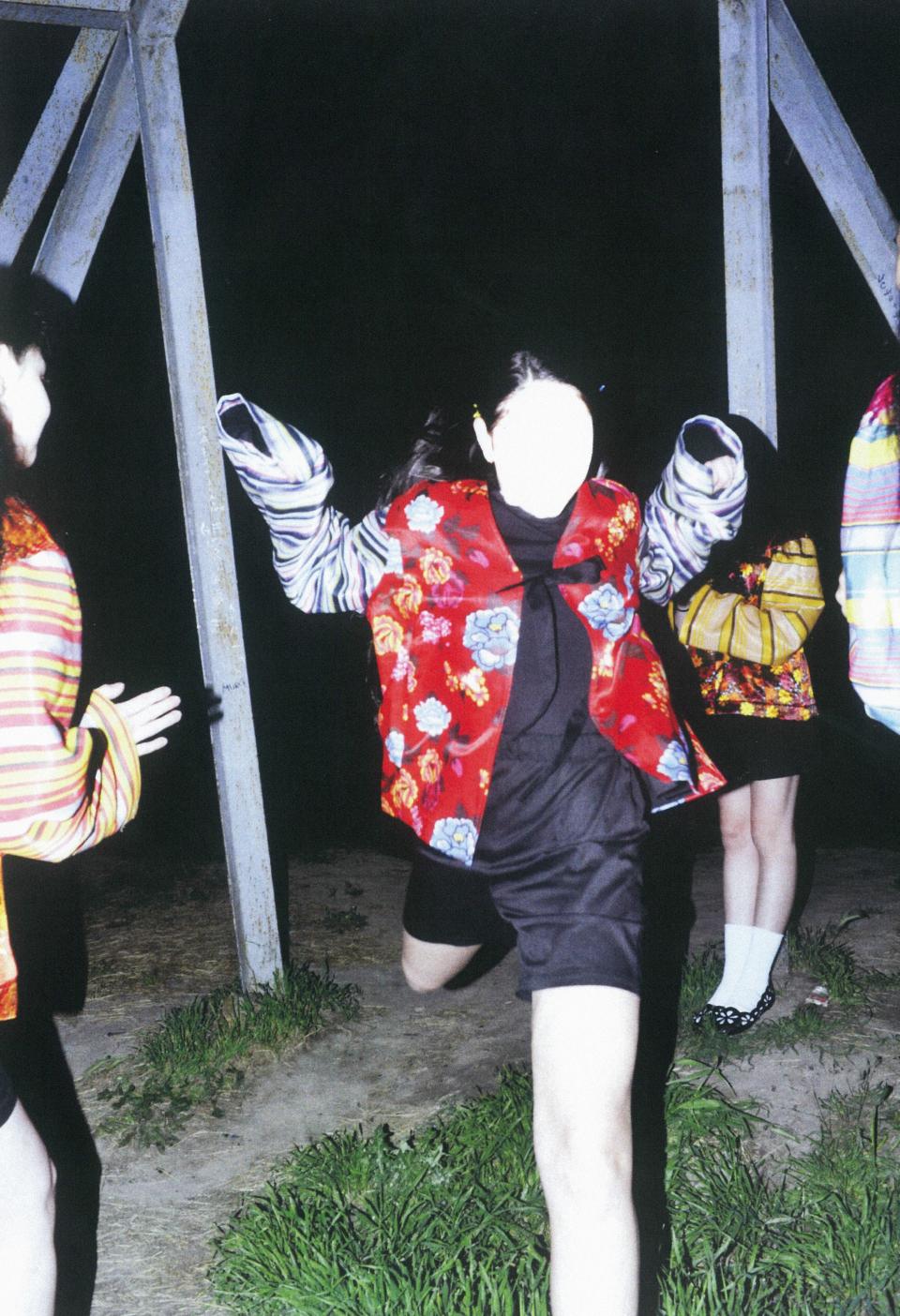

Photo: Hasan KurbanbaevIn a series of photos documenting Kim’s latest collection by the Uzbek photographer Hassan Kurbanbaev, young women are dressed in Korean jeogori made from traditional Uzbek fabrics (called bekasam) as well as Soviet textiles like jacquard viscose. The fashion photographs are interspersed with images of Uzbek and Korean foods: a loaf of lepeshka (a flat Uzbek bread shaped like a saucer) and the salad morkovcha (a Soviet-Korean version of kimchi that has become a ubiquitous dish in Russia). “For me it’s not just food but the most organic mixing of cultures that lived [in] Tashkent,” she says. “That dish [morkovcha] doesn’t exist in Korea. Soviet-Koreans just made it because carrots were available.” The same kind of repurposing and adaptation is celebrated in Kim’s clothing: “If we [Soviet-Koreans] had to make a traditional dress, it would be from Uzbek and Soviet fabrics.”

This insight has led Kim to attempt to make a national dress for the Koryo-saram, a garment that recognizes the complicated history of her people—a history that has been suppressed for generations. Kim’s 12 kaleidoscopic interpretations of the jeogori, made with Uzbek and vintage Soviet fabrics, feature delicious floral graphics and bekasam sleeves decorated with richly colored stripes. “Now I feel that this costume is my mission, and I’m finding a way to do it within Uzbek, Korean, and Russian cultures.”

jkim-tashent.jpg

Photo: Hasan KurbanbaevOriginally Appeared on Vogue