Bradley Hospital holds 'reunion' for intensive OCD program kids, families, clinicians

EAST PROVIDENCE — Manny Padilla was about 8 years old when he began to experience symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“I started having so much anxiety and I would just be like throwing up, having stomach aches, nose bleeds, all that stuff,” he said. “I thought there was something physically wrong with me. I thought I had something that was not treatable.”

RI children in crisis: Why doctors have declared a mental health emergency

Some of his anxiety involved his mother, Lori Padilla.

“My mom would go out for 10 seconds and I’d be, like, Where is she? What happened? What's going on?”

At school, Lori recalled, “he wasn't able to focus, he wasn't able to write, he wasn't able to talk to anybody. Kids were not understanding. He was getting bullied. He wanted to be part of the kids yet he couldn't.”

The staff at the Cranston public school he attended tried to help, Lori said, but they were not equipped to deal with her son’s OCD. Eventually, she began to home-school Manny. But his OCD was intensifying, and by January of this year, the pain of living with OCD had become so intense that Manny, now 17, began to contemplate suicide.

Contemplation led to an attempt.

“I basically tried to kill myself,” Manny said.

Someone saved his life.

And then, over the course of almost four months, the staff at Bradley Hospital’s Intensive Program for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder helped move Manny toward mental well-being.

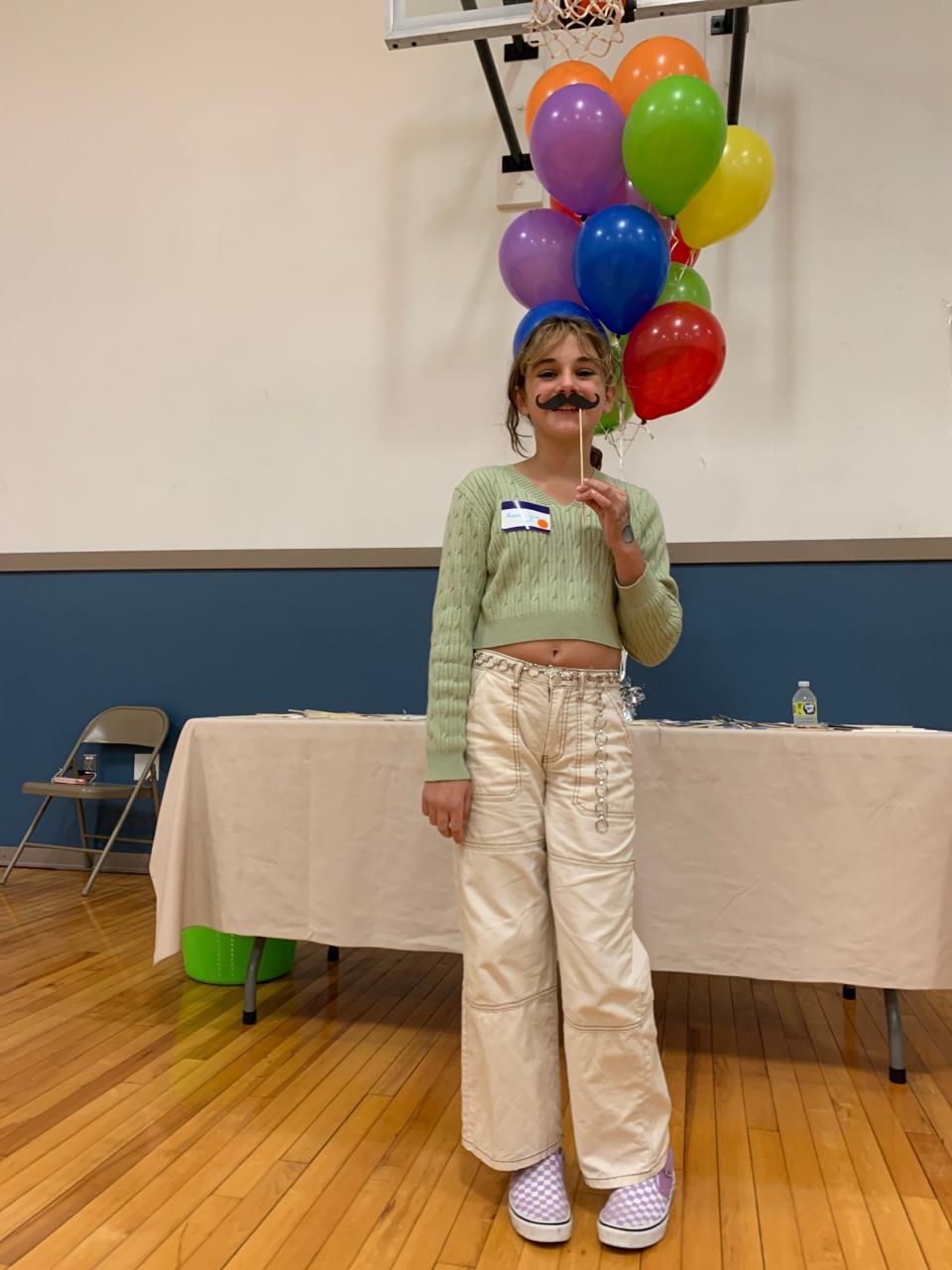

And it was that success that brought him and his mother back to Bradley, a Lifespan facility, last weekend to join other program graduates, families and clinicians in a celebratory program member reunion, said to be the only such gathering in America. More than 200 children, adolescents and family members attended.

'Repeatedly checking on things'

Joining the mother and son as they waited to join the reunion festivities was Bradley clinical psychologist David W. McConville, a member of the team that treated Manny. The OCD program is outpatient, but family involvement, including visits to the home, is key.

“Manny is a really special, unique kid,” McConville said, turning emotional, “but there are also some commonalities in his story — the way that OCD affects school and affects relationships and the confusion, like, ‘What the heck is this?’ There's a universality about that with all with many of the families that we treat.”

On its website, the National Institute of Mental Health defines OCD as a condition “in which a person has uncontrollable, reoccurring thoughts ("obsessions") and/or behaviors ("compulsions") that he or she feels the urge to repeat over and over… These symptoms can interfere with all aspects of life, such as work, school, and personal relationships.”

Among the common obsessions, according to the institute, is “having things symmetrical or in a perfect order.” Compulsions include “excessive cleaning and/or handwashing; ordering and arranging things in a particular, precise way; repeatedly checking on things, such as repeatedly checking to see if the door is locked or that the oven is off [and] compulsive counting.”

Treatment options include medication or psychotherapy or both. Bradley's Intensive Program for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder combines the approaches and offers other services as well.

Also joining McConville and Lori and Manny was Jennifer B. Freeman, director of Bradley’s Pediatric Anxiety Research Center and a professor at Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School.

Freeman said: “Our Center has clinical programs, outpatient programs, partial programs, a whole research program and lots of training: training of new staff, training of new doctors, training of all manner of people. And the special part is that all of those things work together so that we are constantly trying to figure out what's the best way to treat OCD.”

In search of solace

In her quest to find peace for her son, Lori Padilla, a single mother of four, tried many interventions. Manny was an inpatient at other hospitals and while she praised their efforts, Lori said they were insufficient to meet her son’s significant needs. When Manny was finally accepted into Bradley’s outpatient OCD program, Lori said she was elated.

And, she said, the results have proved its worth.

“This program was amazing,” she said. “A life-changer.”

During this autumn of 2022, Lori and Manny continue to work with McConville as they seek to write the next chapter.

Lori said her son “has become very proficient with music. That's kind of his way of expressing himself.” With that in mind, she said, “he is exploring his options with work and music.”

Asked how he feels after completing the program compared to before he started, Manny said: “Like ten times better.”

And the reunion that was about to begin?

“I’ve already met some people that I know and I was just like, wow, I kind of miss this. I feel a relief because I don't really need it anymore but it’s just so, so good to be back.”

Brown study: Can trauma be handed down from one generation to the next?

Intensive Program for OCD

Bradley's Intensive Program for OCD treats children and adolescents age 5 to 18. Contact the program at (401) 432-1516 or visit the web site: https://www.lifespan.org/centers-services/intensive-program-obsessive-compulsive-disorder

Suicide prevention resources: Where to turn if you are considering suicide

Anyone in immediate danger should call 911.

Other resources:

BHLink: For confidential support and to get connected to care, call (401) 414-LINK (5465) or visit the BHLink 24-hour/7-day triage center at 975 Waterman Ave., East Providence. Website: https://www.bhlink.org

The Samaritans of Rhode Island: (401) 272-4044 or (800) 365-4044. Website: samaritansri.org

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: (800) 273-TALK, or (800) 273-8255

The Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741 “from anywhere in the USA, anytime, about any type of crisis.”

Butler Hospital Behavioral Health Services Call Center: Available 24/7 “to guide individuals seeking advice for themselves or others regarding suicide prevention.” (844) 401-0111

Thrive Behavioral Health's Emergency Services: 24-hour crisis hotline (401) 738-4300.

Prevent Suicide in Rhode Island: a Department of Health resource. If you are in crisis, call (800) 273-8255 or text TALK to 741741. Website: https://preventsuicideri.org/

LGBTQ Safe Zones: BCBS of RI adds 21 more doctor's offices for LGBTQ health care

Veterans well-being: In 2020, 14 Rhode Island veterans died by suicide. New program wants to reduce that number

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Bradley Hospital OCD program holds reunion for kids, families