Brain Center of Green Bay evolved from surgeon's experience with wife who had Parkinson's

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

GREEN BAY – As she neared 50 years old, Ann Lulloff could serve tennis balls without thinking, so ingrained was her muscle memory.

The sport first grabbed her interest as a young girl in La Crosse, and it never let go. She was a competitive player well into adulthood, and coached the St. Joseph Academy girls' tennis team to a state championship title in 1987.

Two years later, she tossed a ball into the air one day, and her racket whiffed through nothing but air. She tried to serve again. And again.

Thirteen years earlier, at age 36, she'd lost her sense of smell. Doctors found nothing abnormal on her CT scans, but the sense never returned. Then panic attacks began, debilitating enough that she'd lose her balance while shopping at the mall, a place she had joked inspired nothing short of joy. She'd lean on walls, winded and overwhelmed. Her psychiatrist at the time diagnosed depression.

Now tennis was gone too. Ann couldn't follow the speed of the ball enough to serve, volley or smash it. Her movements became slow and wooden; the quality of her play — once a point of pride — crumbled under angles and lines that no longer made sense.

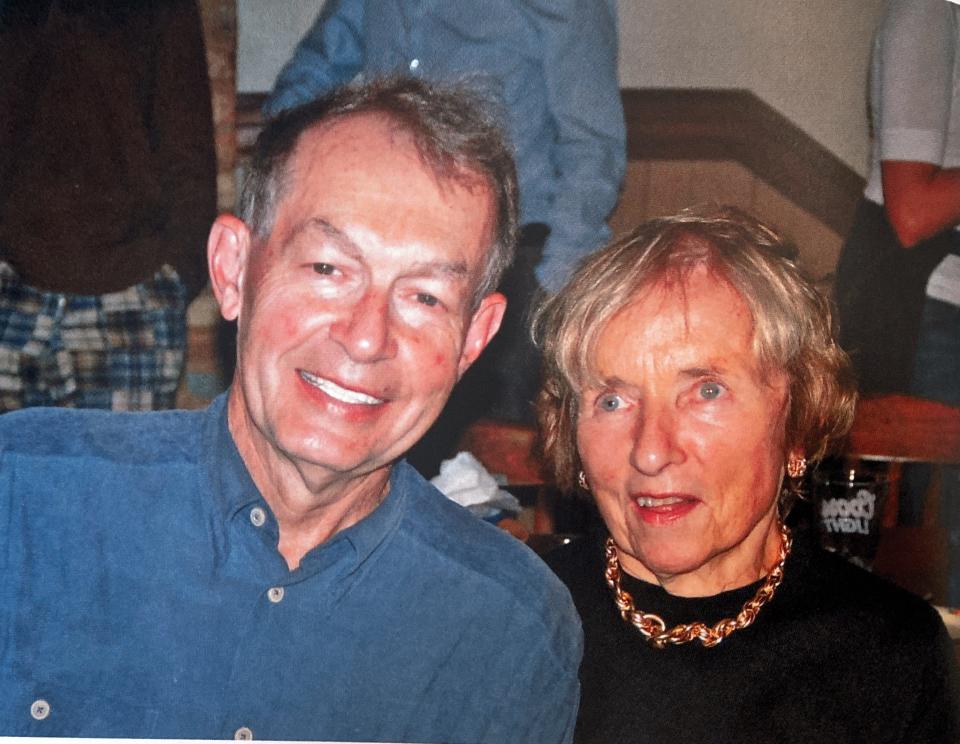

Ann was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease on New Year's Eve 1989, a diagnosis that shifted the way her husband, Dr. Rolf Lulloff, understood the brain — its needs, mechanisms and performance. An orthopedic surgeon by trade, Rolf devoted himself from then on to studying the brain in all its wonders and heartbreaks, in part as a means to keep his promise to Ann: "I will always be with you in fighting this damn disease."

"She taught me that I had to look at her through her brain and not my brain," he said.

Ann died in 2021, four years after her husband and a team of other medical doctors co-founded the Brain Center of Green Bay.

Though not a medical clinic and not intended to take the place of primary care doctors, the nonprofit center is a resource for families affected by brain disease or brain conditions. It is committed to dislodging stigmas associated with neurodegenerative diseases, and helping stimulate good, lifelong brain health practices.

"In this day and age, we like to label things. We like to put a diagnosis on them. Our brains don't carry a diagnosis. They carry an existence. They carry experience," Rolf Lulloff said. "There's a genetic factor that enters in, but more than that, it's our experiences and how we learn from them — and how much we allow them to dominate us."

Forming new healthy habits is among the key missions of the Brain Center. Well-established in the science community, the concept is that neurons in the brain are capable of rewiring throughout life in a phenomenon called neuroplasticity. It's the practice of forming new habits to compensate for a disease robbing the functionality of old ones.

Part of treatment is to get the brain to 'wake up again'

On a recent frigid Tuesday, Rolf welcomed his colleague and friend, Dr. Dave Donarski, over to his Allouez home for a tradition he dubbed "Tuesdays with Dave" eight years ago. Donarski, a retired psychiatrist and another co-founder of the Brain Center, used to treat Ann in the wake of her Parkinson's diagnosis.

Ann had three major falls in 2010 that made it unclear if she'd ever walk again. She'd broken three ribs, suffered from subdural hematoma (brain bleeding) and broken her hip over the course of seven months.

As a result, she relied not only on a walker, but moved with a shuffled gait. Rolf worried the way she walked would lead to another fall. He recalled his work with patients recovering from knee surgery: To get people to change how they moved, he first had to change their minds.

As an orthopedic surgeon, Rolf had recently worked with an 85-year-old man who'd broken his hip. Following treatment, he said the patient returned complaining that he couldn't lift his left leg. Rolf lifted his leg for him on the doctor's bench and asked him to lift his working leg. They spoke of other topics as Rolf assisted him in this exercise.

Pretty soon, the patient was moving both his legs without help.

"He told me, 'Doc, you're a miracle worker.' I said, 'No. Your brain forgot how to work with this — and we taught it to wake up again,'" Rolf said.

Neuroplasticity, according to Dr. Norman Doidge, author of the book The Brain's Way of Healing, is the part of the brain that, through an activity and mental exercise, enables it to change its own structure and functioning.

Learning, in other words, "switches on" parts of the brain that can then change its neural structure, Doidge wrote. As Rolf moved his patient's leg, his brain was able to take over.

Donarski likes to think about neuroplasticity from the perspective of an athlete.

"So often, athletes only know one thing, and this is, 'The harder I work, the better I can play,' instead of being able to play it right," said Donarski, a former athlete himself. "It isn't just your muscles that need to work and heal, your brain needs to work just as hard."

Rolf folded in some of those concepts with Ann's walking.

Every day, in place of her walker, he would walk with her from one room to the next, one big step with the left foot, one big step with the right. They started with the 90-foot distance between their bedroom and the kitchen table. The moment she started to shuffle, they would stop.

"I said 'If we allow you to shuffle, then it reinforces your brain into the habit of shuffling. You already know how to shuffle. We need to train your brain,'" Rolf said.

They'd walk from the bedroom to the kitchen, then the bedroom to the front door. The walker would always be nearby, and they'd stop if she started to shuffle or if she got tired.

Within three months, the two of them could walk around the block.

"Did it make a difference? We had no falls," Rolf said. "We went nine years without a fall."

Good mental health practices fuel good brain health

The brain needs to be stimulated in a lot of different ways to function well, said Dr. Gail Carels, a coach at the Brain Center of Green Bay and a retired family medicine clinician.

Adages like, "If you don't use it, you'll lose it” become critical when a neurodegenerative disease enters into the equation. Once these diseases disrupt the autonomic nervous system — the part of the nervous system responsible for bodily functions — everyday functions like balance and digestion become harder.

These physical hardships quickly take a toll on mental health, said Carels. Loneliness, anxiety and depression are less emphasized symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases, but they can impact eating, sleeping, socializing.

At the Brain Center, coaches listen to their clients' stories, validate their experiences and brainstorm with them (and, if appropriate, their caregivers) about how to improve and maintain good brain habits, Carels said. Clients with whom Carels has worked described a typical visit to the doctor as transactional, "like it's all business." The physician performs a check-up, jots down observations, asks about medications, and sometimes prescribes new ones.

But to understand neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's and early onset Alzheimer's is to listen to the stories being told that don't just revolve around medical problems, but also the way a people live: their eating habits, their social behavior, their sleep, their mobility throughout each day.

Kindness is an important part of care

A decade after she was diagnosed, the impact of Parkinson's on Ann Lulloff took a disconcerting turn. Every morning, Rolf would wake his wife up by telling her he loved her. One morning, Ann asked if her mother had woken up yet. Her mother had been dead for 12 years.

"I was naive enough to the point that I went upstairs and got her mother's death certificate. I came down and I showed it to her. And she looked at it, said 'Oh,' and handed it back to me. I felt guilty about it all day long. I thought, 'You dummy. You're looking at this through your brain, not her brain. Her brain says her mother isn't dead,'" Rolf said.

Two days later, Ann asked again whether her mother had woken up yet. He told her she was still sleeping, which left him unsatisfied. The next day, when she asked, Rolf Lulloff said she was asleep in heaven. The issue never came up again.

Compassion, Lulloff would learn, is a generous tool when working with people whose brains function differently, whether they have schizophrenia, anxiety, or depression, and he and other volunteers at the Brain Center use it as they would any other resource. That understanding has a far greater reach than arguing with someone over perception.

"In dealing with ALS, with Parkinson's, this is a journey," Rolf Lulloff said. "It's not cast in stone — we have a chance to make a difference."

Being kind also feeds into our own well-being, according to Dr. Richard Davidson, a world-renowned neuroscientist based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Where positive emotions meet well-being is at the heart of Davidson's brainchild, Center for Healthy Minds. We are born with moral compassion, Davidson asserts, and emotions like anger and anxiety neurologically inhibit our ability to thrive.

In a study Davidson cited, two groups of 9-month-old babies were shown two very different puppet shows. In one, the puppets help each other; in the other, the puppets steal from each other. Nearly 100% of the babies prefer the one showing kindness.

“This is not just a weak preference that you see at that population level. This is everybody," Davidson said. "This allows us to — with a lot of confidence — state that in fact, we are born to be kind."

Rolf Lulloff views himself as a coach because he sees his role as an agent of encouragement in someone else's life. If his client reports having a string of bad days in which they didn't stick to a healthier diet choice or commit to chair yoga, his role is to elevate them.

"Nobody needs to be chewed out and criticized. They need to be boosted up. Your patients are human. It's not rocket science. It's caring," Lulloff said. "And the best way to stimulate them is to be positive."

High quality of life defeats everyday obstacles

Ann wept in the car following her diagnosis that fateful New Years Eve. She grieved to her husband that she would never see her children marry, never meet her grandchildren, never again play tennis. Her life, she feared, was summarily over.

Rolf Lulloff promised they would "fight the damn disease" through a mixture of science and matrimonial devotion. He made every day with his wife count, never skimping on quality time. And as a doctor, as much as a husband, he followed what he called the "L" words: "I looked, I listened, I learned, I liked, I loved."

"In dealing with brain issues, this is what we have to do," he said.

They traveled to Europe, bought a condo in Florida. Cuddling, Rolf Lulloff said, was a powerful, everyday act. And they tried laughing off the bad days, too.

Ann's life far exceeded expectations. She lived with Parkinson's for more than 45 years — the first 13 undiagnosed — and died peacefully surrounded by her eight grandchildren, three of whom she saw off to college.

"We made a difference. We had a wonderful, wonderful life together. And we had a quality of life all the way through," Rolf Lulloff said.

Years ago at their Florida condo, the couple was entertaining friends when they noticed a particularly stunning sunset. The condo had a spiral staircase up to the rooftop, which their friends climbed up to better their view. Ann, at 72, worked herself up the stairs one at a time, Rolf behind her. When she reached the top, a sunset and a Manhattan cocktail awaited her.

"We had a Manhattan and watched a beautiful sunset. Life goes on," Rolf said. "You find ways to make things happen."

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Brain Center of Green Bay teaches clients healthy habits, new routines