Brain study reveals 41% of young athletes under 30 had signs of CTE

Aug. 28 (UPI) -- The authors of a scientific study published Monday say they have found alarmingly high rates of the brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy among younger athletes.

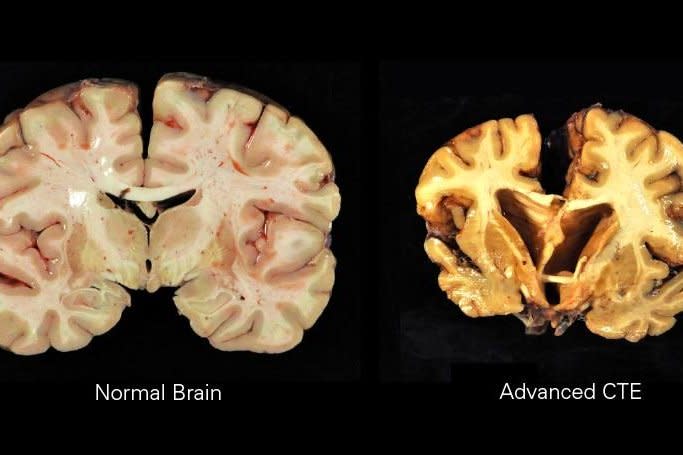

CTE has already been found to be quite common among retired National Football League veterans who have struggled with declining brain health due to the condition, which is caused by repeated blows to the head sustained while playing football and other hard-contact sports.

But a study conducted by Boston University CTE Center and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Neurology revealed that the brains of 41% of young athletes under the age of 30 also showed signs of the condition.

"It seems to be well accepted now that you can play at a very high level of elite American football or ice hockey and get CTE," study co-author Ann McKee said in a release. "But we're seeing the beginnings of this disease in young people who were primarily playing amateur sports."

The results, she said, suggested that even young, amateur athletes who participate in physical contact sports at a low-profile level appear to at risk, even though their playing careers are comparatively short.

In the study, Boston University researchers examined the brains of 152 contact sport participants who had died under age 30. Some 41.4% of them had signs of CTE.

More than 70% of those diagnosed were merely amateur athletes who'd played sports like football, ice hockey, soccer, rugby and wrestling. Among those found with CTE was the first American female athlete ever diagnosed with the condition -- a 28-year-old collegiate soccer player.

The study included samples kept at the UNITE Brain Bank, a repository of more than 1,400 brains donated after death for study run in partnership with the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

McKee said most of the young athletes whose brains were studied died either by suicide or unintentional drug overdoses, while interviews with family members revealed that 70% of all the athletes -- even including those who did not have CTE -- showed "meaningful symptoms of depression and apathy" before their deaths.

The results showing 40% of young athletes having CTE are "remarkable," she said, given that studies of community brain banks indicate that fewer than 1% of the general population has the condition.