Brazil’s Lula Gets New Nemesis in Inflation Fight With El Nino's Return

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- A bumper harvest helped Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva defy pessimistic economic expectations during his first year back in office as Brazil’s president. Fickle Mother Nature is poised to make repeating the feat tougher in 2024.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Apple to Sell Watches Without Oxygen Feature After Legal Setback

Singapore Minister Quits After Biggest Graft Case Since 1986

Stocks Drop as Solid Data Fuel Fed-Pivot Repricing: Markets Wrap

Dimon Says China Risk-Reward Equation Has ‘Changed Dramatically’

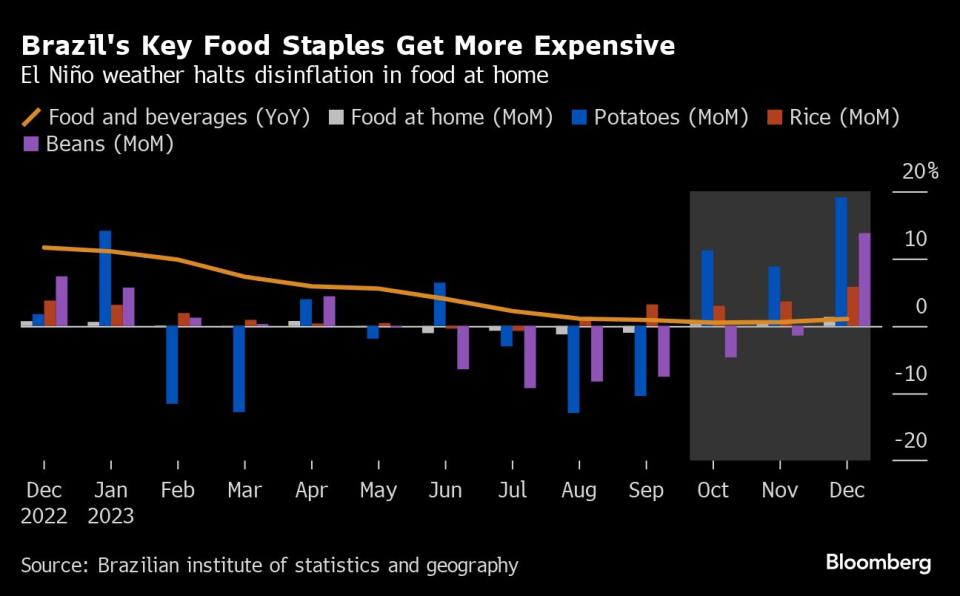

El Nino, the weather phenomenon with a history of disrupting agricultural powerhouses like Brazil, has returned with a vengeance in the South American summer, unleashing torrential rains in parts of the country and leaving others uncommonly dry. Prices of staples like rice and potatoes are soaring as a result, challenging both the central bank’s plans to continue the interest rate cuts Lula demanded and his campaign promises to deliver cheaper fare to everyday Brazilians.

“El Nino is worse than expected,” said Adriano Valladao, an economist at Banco Santander Brasil SA. “We forecast worse inflation in January, with weather impacting the most volatile food items.”

Annual inflation continued to slow to within the central bank’s target range in December, official data released last week showed. But food prices bucked the trend, as El Nino weather effects that have already disrupted production and caused spikes in parts of Asia began to hit Brazil.

Potatoes, beans, rice and fruit all became more expensive amid high temperatures and heavy rains, while the overall cost of food at home — where effects are most pronounced — rose 1.3%, far faster than the 0.75% increase the month prior.

Economists are starting to revise growth estimates downward. And if the cyclical phenomenon proves as severe as it was nearly a decade ago, it could add as much as 0.8 percentage points to cumulative headline inflation totals for 2023 and 2024, most analysts estimated in a December central bank survey.

El Nino has caused the bank to increase its inflation estimates, Diogo Guillen, the monetary authority’s director of economic policy, said last week at a virtual event organized by JPMorgan Chase & Co.

But, he added, “it is not something that changes everything.”

Rising Prices, Falling Forecasts

In South America, Peru and Colombia face bigger El Nino dangers, thanks to potential impacts on hydropower, agriculture and fishing, said William Jackson, the chief emerging market economist at Capital Economics.

Argentina, on the other hand, is likely to enjoy some benefit from the phenomenon that may help alleviate record droughts that have devastated the economy.

“In terms of risks, Brazil sits somewhere in the middle,” Jackson said.

Read More: El Nino Rains Fuel Bumper Harvest for Paraguay Soybean Exporters

Some parts of Brazil may also receive a boost from El Nino-related storms. But the importance of agriculture to its economy means that even small harvest disruptions in other regions can pose sizable risks. Meteorologists see El Nino’s impact on South America beginning to weaken, but production shortages have caused Itau Unibanco SA to revise its agricultural GDP forecast for 2024 to 0.7%, down from a previous 2.5% estimate.

“In an extreme scenario,” Itau economist Natalia Cotarelli said, “we could see a negative agriculture GDP.”

Even if El Nino remains relatively mild, the agriculture sector isn’t expected to grow in 2024, according to Felippe Serigati, a researcher at the Center of Agribusiness Studies at the Getulio Vargas Foundation think tank.

Other El Nino effects are already clearer. Extreme storms in southern Brazil, a major farming area, caused floods that delayed this year’s planting in Rio Grande do Sul, the country’s top rice-producing state. Wholesale prices of rice rose 40% in 2023 as a result, with costs increasing nearly 6% in December alone.

“The cost of this year’s crop has increased significantly due to climate challenges,” said Alexandre Velho, a farmer and the head of Federarroz, an association of rice producers.

Prices for fresh root crops and legumes, like potatoes, jumped 8.1% last month, according to official data, after poor harvests in the southern region. The cost of potatoes rose 19% in December.

Produce is only likely to get more expensive in the coming months, said Margarete Boteon, an economics professor at the University of Sao Paulo. The rainy weather also hurt wheat harvests and is likely to result in higher flour prices, according to producers’ group Abitrigo.

Read More: Brazil’s Dryness Threatens to Drive Up Instant Coffee Prices

Brazil’s northern and central agricultural hubs, meanwhile, received less rain than expected, which has dented forecasts for soybeans, Brazil’s top agricultural export product. Producers in Mato Grosso, the largest source of soy, reported the need to replant 4% of the area, resulting in higher costs, according to state’s rural economy institute.

Oilseed prices aren’t expected to increase, but many farmers now seem certain to face financial losses, said XP Inc. analyst Leonardo Alencar. Companies like SLC Agricola SA, meanwhile, have already revised guidance downward.

Mounting Risks

Brazilian policymakers may take solace from the fact that Latin America has so far experienced relatively mild effects, Capital Economics’ Jackson said.

El Nino caused Colombia’s central bank to remain cautious for months as its major South American counterparts cut interest rates, but it delivered its first reduction in three years in December. El Nino battered Peru last year, helping push its economy into recession. But its outlook has begun to brighten, and while risks persist, the chance that it will experience weak or nonexistent effects in 2024 are now rising, the central bank said last week.

In Asia, by contrast, spiking inflation forced many monetary authorities to put off easing cycles they had planned to launch in the second half of 2023.

Read More: Brazil’s Export Boom Rekindles Memories of Commodity Bonanza

Still, El Nino highlights the growing risk of extreme weather to countries that depend heavily on agriculture to spur their economies, especially as major climate events — including unexpected floods and droughts — become more frequent. That will likely make weather an even more important factor for inflation and economic performance.

“Longer-term risks from climate change will make severe weather events more frequent and probably lead to higher and more volatile inflation,” Jackson said.

--With assistance from Clarice Couto, Oscar Medina, Jonathan Gilbert, Andrea Jaramillo and Marcelo Rochabrun.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.