Brevard County Commissioner argues Florida should kill manatees to save them

As threatened manatees die in unprecedented numbers throughout Florida, mostly from starvation due to a dearth of seagrass, its staple food, a Brevard County Commissioner is proposing "culling" sea cows like states do with their excess bear, wolf and deer populations.

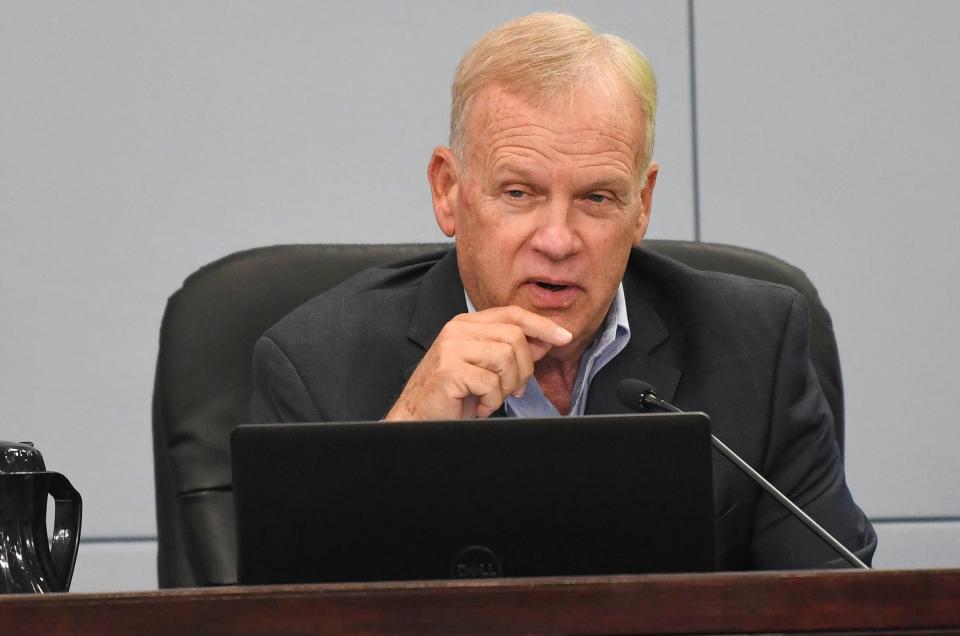

Commissioner Curt Smith floated his dramatic proposal last week at the end of the last Commission meeting. It was during one of those routines at the end of regular meetings when commissioners share dull house-keeping items. He prefaced his presentation to his fellow commissioners and the people in the room, saying he hoped "not to bore you guys."

He then dropped his bombshell, and he wasn't joking.

"I think the elephant in the room for seagrass is the sea cow, which is called the manatee," Smith told fellow commissioners at the March 22 meeting. "Nobody's addressing the fact that we have too many manatees, eating such a small amount of seagrass."

His suggestion wasn't meant to be callous, Smith later said Monday, but to start a serious conversation about how manatees have outgrown the capacity of the Florida's seagrass beds needed to sustain them and how current approaches are failing.

The never ending debate: What is to be done about Florida's most beloved marine mammal?

But state and other conservation biologists say he's on the wrong side of what science shows, however, and that the increase of manatees pales in comparison to the millions more Floridians who've moved to coastal watersheds in the five decades since the feds listed sea cows among the nation's most at-risk species.

"Manatees are a cornerstone species in Florida’s estuarine environments and are federally listed as Threatened," Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission officials wrote in an email. "Regardless of their listing status, manatees are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and take (killing or hunting) of these animals is not permitted."

Manatees die in record numbers: A record 1,100 manatees starved to death last year from a man-made famine. Finally, the pace slows

A record 1,100 manatees starved to death last year from a man-made famine that has choked out the seagrass beds around the state. Up and down Florida, sandy outcroppings and estuaries have become sea cow mass graveyards as more manatees succumbed to the ravages of hunger every day.

The death toll was so bad that in April last year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared the die-off an Unusual Mortality Event. In a first-of-its kind pilot project to try to stave off further starvation, state and federal biologists have been feeding manatees at the FPL plant since mid December. They plan to feed the manatees through the end of March.

Smith spoke on the topic because he represents Brevard County on the Indian River Lagoon Council, the regional body that runs the Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program.

He compared the manatee situation to the Florida black bear, in which the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission allows hunts when the bear population outgrows the habitat needed to support them.

"When the bear population exceeds that, what happens? They have a hunt. They cull the herd. They decrease the population. Same thing with deers," Smith told fellow commissioners. "You know and I know that would be very difficult with manatees, because everybody loves the manatees. If you kill a manatee, my God, the world would come to an end. But I think something has to be considered along those lines," Smith said.

In 1974, the Florida black bear was listed as threatened throughout most of Florida. But after reviewing the species' status, FWC removed them from the state's threatened species list in 2012. Manatees were listed as "endangered in in 1973. Florida followed with its own protections, passing the Florida Manatee Sanctuary Act in 1978. But after decades of improving annual population counts, the federal government upgraded them to "threatened" in 2017.

When asked Monday to clarify his March 22 statements, Smith said that "the manatee's already saved, now we're killing them."

"I just hear all the comments, and I live on the river. I've been listening to this subject for 20 years now," Smith told FLORIA TODAY on Monday.

Should we feed sea cows in the wild? Manatees warming up to lettuce at FPL power plant

"The problem is it's an emotional issue," Smith added. "How about if helping them is teaching them to be a real manatee and migrate .."We're not treating them like wild animals, we're managing them like pets."

FWC needs to figure out how many manatees are sustainable and wean them off the warm water discharges that lure them to power plants such as Florida Power & Light Co.'s plant in Port St. John, Smith said, where state biologists this winter enacted an emergency pilot project to feed sea cows lettuce.

"A cow munches the grass and leaves the root, so when the cow walks away, the grass has a chance to grow again. With seagrass, that doesn't happen. They pull the grass out by the roots," Smith said at the March 22 meeting. "And so if you have a population of 1,000 manatees, and the environmental will only support 500, it makes sense that they're going to eat themselves out of house and home."

Smith said federal wildlife officials and FWC are "concerned with this but they don't want to mention it in public, and for good reason, because again, nobody wants to see the poor little manatees go away because their sweet and we all love them," Smith said. "But the reality is what the reality is."

FWC officials said that while they hadn't heard all of Smith's comments, but that the agency "is "committed to ensuring a healthy manatee population and will continue to rescue manatees and respond to the Unusual Mortality Event as appropriate."

"In recent years, poor water quality in the Lagoon has led to harmful algal blooms and widespread seagrass loss," FWC officials said. "Researchers have attributed this UME (unusual mortality event) to starvation due to the lack of seagrasses in the Indian River Lagoon. Environmental conditions in portions of the Indian River Lagoon remain a concern."

But as the state's manatee counts doubled over the past two decades to more than an estimated 8,000 manatees, boating advocates warned wildlife officials that seagrass growth wasn't keeping pace and manatees faced imminent famine. Boaters for years shouldered too much of the blame for the manatee's plight, boating advocates said.

Smith, an avid boater, agrees.

But biologists at FWC and elsewhere long have pushed back on the boaters' theory that the manatee population explosion is to blame for eating themselves out of habitat and home. It's much more likely too many people living too close to manatees killed all that seagrass, they say, pointing to all the lush seagrass 10 years ago.

"That seagrass didn't disappear because there were too many manatees," Martine de Wit, who runs FWC's marine mammal pathobiology lab in St. Petersburg, told FLORIDA TODAY at the height of last year's manatee famine.

FWC stats through March 18 show boaters being responsible for 3.4% of this year's 441 manatee death toll, compared with 19 (3.5%) of 537 manatees that had died during the the same time period last year.

Of this year's manatee deaths in Florida, 280 (63.5%) were in Brevard.

Boats typically cause 20% to 25% of the deaths on any given year. Boats have killed 15 manatees in 2022, seven fewer than the state's five-year average.

Of this year's deaths, 297, more than two-thirds, were not thoroughly examined after death but most of those are presumed to have starved because of lack of seagrass and their emaciated appearance.

Boaters point to power plants, too.

Manatees migrate to natural warm water refuges like freshwater springs but also to artificial ones, such as the warm-water discharge zones at power plants. That puts them in areas with scant seagrass during colder months. Before power plants, manatees seldom migrated farther north than Sebastian Inlet on the east coast and Charlotte Harbor on the west coast, fossil records show.

Report sick, injured manatees or violations to 888-404-FWCC (888-404-3922). Cellular phone users can also call #FWC or *FWC.

Jim Waymer is an environment reporter at FLORIDA TODAY. Contact Waymer at 321-261-5903 or jwaymer@floridatoday.com. Or find him on Twitter: @JWayEnviro or on Facebook: www.facebook.com/jim.waymer

Support local journalism and local journalists like me. Visit floridatoday.com/subscribe

This article originally appeared on Florida Today: Brevard County official says Florida should kill manatees to save them