Brexit Britain has forgotten the crucial role the UK played in shaping the Europe of today

Two themes have dominated the debate during the Brexit negotiations: Leavers have repeatedly claimed that Europe “needs us more than we need them”, with feverish anecdotes of Britons buying German cars and French wines; while Remainers have been keen to stress the lopsided nature of the negotiations, suggesting that the 27 EU member states, with a combined economy almost eight times the size of the UK, have significantly more power and sway in the negotiations.

Which side of those two conflicting views you take is usually an indication of how you voted in the referendum, but both are masked in opinion, much of which is formed by ideology.

Irrespective of which side of the fence you are, what has been forgotten since Britain voted to leave the European Union is that the UK has been vastly important and influential in shaping the direction of European integration, and since the end of the Second World War has helped to mould European geopolitics into what it is today.

Without the UK Europe would not be where it is right now – and without a doubt Britain will be missed once we officially leave the bloc on 29 March.

Post-war Britain: helping to shape the continent

Much of the political, military and economic relationships that were formed in Europe following the end of the Second World War up until the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC) were heavily influenced by Britain and the US. Keen not to have Europe fighting each other once again the US pushed for greater integration, often encouraging the UK to take the lead.

There was a belief that an integrated Europe would both embed Germany into the continent, nullifying the threat of another European war and also serve as a deterrence to any Soviet aggression. Britain was, however, not keen on sacrificing sovereignty for a supranational project and instead opted to push for an intergovernmental approach to European integration.

Germany would go on to become arguably Europe’s most influential nation; without the UK’s initial push, this might not have happened at the pace it did

In 1945 Ernest Bevin became foreign secretary and, unlike his predecessors, he was given free reign by his prime minister, Clement Attlee, to determine the direction of British foreign policy. Bevin understood that he was arguably the only man in government in Europe who had the ability to influence the Americans while also maintaining a functioning relationship with allies across the continent.

It was this relationship, alongside the reluctance to sacrifice sovereignty for integration which drove British foreign policy.

In 1948 Britain, France and the Benelux countries signed the Treaty of Brussels which was intended to organise defence efforts against any potential aggressors, particularly the Soviet Union. It built upon the Treaty of Dunkirk which had been signed by Britain and France and was consistent with Bevin’s “grand design”, which outlined his ambition to build political, military and economic co-operation with western European nations.

It was intended to demonstrate to the US that Europe was serious about its own defence, and the signing of the treaty marked an important stage in the post-war period. It was a step towards the creation of anti-Soviet military alliances and, although critics branded the agreement “anti-German”, it ultimately laid important groundwork for military co-operation.

One month after the singing of the treaty Bevin, alongside his French counterpart, Georges Bidault, wrote to US president Harry Truman requesting his assistance in “the effective defence of western Europe” and, after a series of secret negotiations in Washington, the US, Canada, Portugal, Denmark, Italy, Iceland and Norway all signed the Treaty of Brussels and by doing so formed Nato.

Sir Nicholas Henderson, a former British diplomat, described Nato as a “British invention” and, although this embellishes the truth slightly, there is certainly an argument that Britain, second to the US, was the most keen to push for this alliance and highly influential in its formation. This is partly due to Bevin’s desire to work with both the US and Europe, but also due to his worry that he could not rely on the continent or the US alone when it came to defence.

Britain’s influence with Nato continued long past Bevin’s time at the Foreign Office, and in 1954 – after the collapse of the French proposal of a European Defence Community where French, British and German soldiers would fight side by side – Britain pushed for Germany to be allowed to join the alliance. Anthony Eden, then Britain’s foreign secretary, secured Germany’s admission by negotiating with France and establishing limits on German rearmament.

The UK agreed to station four divisions and a tactical air fleet to accompany the US divisions already on the European mainland to reassure France it would act as a counterweight to German military forces.

This eased the fears of the French, who had insisted on safeguards against any unwelcome developments from Berlin. The move was critical in Germany’s reintegration into Europe and, without the UK pushing for its membership of Nato, Germany’s recovery and rehabilitation would have undoubtedly been hampered.

Germany would go on to become arguably Europe’s most influential nation and, without the UK’s initial push, it could be argued that this would not have happened at the pace that it did. The UK’s role and influence over Nato, coupled with its relationship with the US, had a significant impact on military co-operation in Europe and demonstrated why Britain was so important to the continent and how much influence it had in shaping outcomes.

Another pertinent example of the UK’s influence during this period through the formation of the Committee of European Economic Co-operation (CEEC), which later became the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) and ultimately the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

With Europe still feeling the aftermath of the devastation of the Second World War, the continent turned to the US for financial aid. Then-US secretary of state George Marshall offered a large aid proposal which would later be dubbed the Marshall Plan. The US was adamant the money could not be treated as a short-term solution but instead used to resolve the long-term structural problems that existed on the continent.

There was a consensus in Washington that further European integration was the solution and that many of Europe’s problems were partly due to a lack of unity. There was significant pressure on Britain from the US to take the lead on integration and aid appeared to be predicated on this. Upon Marshall’s initial offer Bevin met with his French counterpart Bidault to discuss how best to approach Washington, and it was through Bevin’s persistence that 16 western European nations joined together to form the CEEC.

The organisation co-ordinated the countries’ recovery plans and presented them to Washington as a single programme, but importantly for Britain ensured decisions were made through a unanimous vote system, not a majority, giving Britain the ability to veto if necessary. Britain was able to ensure this initial integration took place through intergovernmental means rather than supranational institutions, and it was through the CEEC Europe was able to demonstrate this co-operation was possible, satisfying the US, while simultaneously not sacrificing a huge amount of sovereignty.

Throughout the Marshall Plan negotiations Bevin took a significant lead, described by his biographer, Alan Bullock, as his “most decisive personal contribution as foreign secretary”. By the time the plan came to an end, it helped to kickstart the European economy and by 1951 the US has provided approximately $13bn of aid, of which $2.7bn had gone to Britain.

Along with securing aid, the OEEC, which replaced the CEEC in April 1948, was instrumental in several important initiatives, including the European Payments Union and the International Customs Union Study Group (which was set up on Bevin’s initiative), all of which helped to shape the future of Europe and pushed countries to work together and integrate.

The OEEC – which later became the OECD – paved the way for Europe’s integration process and, as an intergovernmental organisation, proved to be popular during the 1950s as it was viewed by many as an alternative to the more far-reaching proposals that were coming from the continent. As a permanent intergovernmental organisation, its work was unspectacular but it played an import role in helping to rebuild Europe.

It was also a perfect example of Bevin’s “grand design” and, during his time in office, he was able to implement an unprecedented level of economic, political and military co-operation for a period of peacetime. Much like Nato, the CEEC/OEEC demonstrated that British influence over Europe and the role the UK has played in pushing for co-operation but also ensuring growth and prosperity of the entire continent.

Britain inside the EEC/EU: shaping the direction of the union

Britain’s aversion to sharing or losing sovereignty to a federal Europe was the primary motivator for the use of intergovernmental organisations in the initial stages of European integration. It did, however, become a stumbling block for the continent’s desire to integrate further and European powers soon became frustrated – in fact, in the early 1990s during the Maastricht negotiations French president François Mitterrand noted that “Europe has got used to British opposition and to making plans without the UK in the expectation it would join later”.

Britain didn’t just want to join the train. It wanted to be in the driver’s cabin

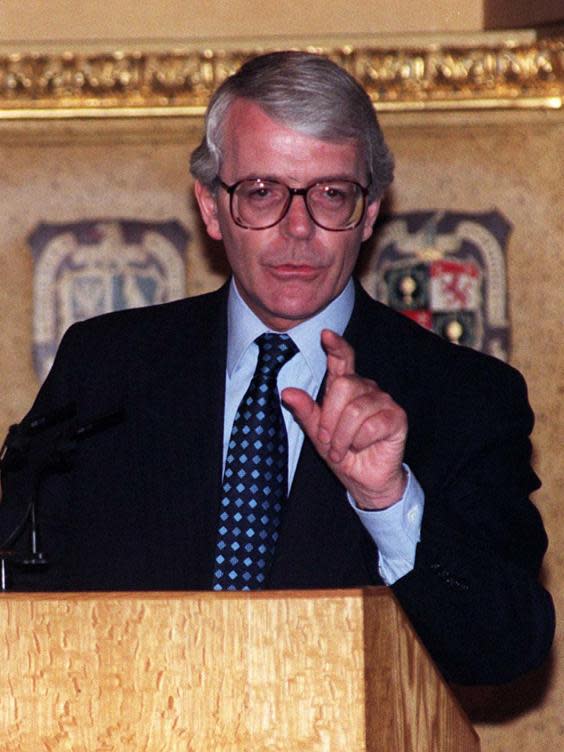

John Major

This is a perfect characterisation of Britain’s role in Europe for almost two decades – in the 1950s French diplomat Jean Monnet, dubbed “The Father of Europe”, proposed a Coal and Steel Community and did not include Britain in the initial negotiations. The UK was also left out of several initiatives including the Schuman Plan, the European Defence Community (although this was ultimately unsuccessful), the Pleven Plan, the Messina negotiations and the creation of Euratom and the EEC.

While European nations pushed forward with their plans to integrate and worked together through the EEC, their economic growth soon began to outstrip Britain’s. It was at this point British reluctance to integrate dimmed and the UK made several attempts to join the bloc before finally being granted membership in 1973.

Within years Britain developed the reputation of being a somewhat “awkward partner”, but this characterisation fails to encompass the influence and role Britain has played in developing the EU.

For two decades between 1950 and 1973 Britain found itself marginalised because of its fear of integration – the UK was left outside the decision-making process and not part of discussions that it would be affected by, but as a member Britain used its influence to ensure the EU would develop into a form of political authority that could manage relations and issues between all member states in way that suited the British vision.

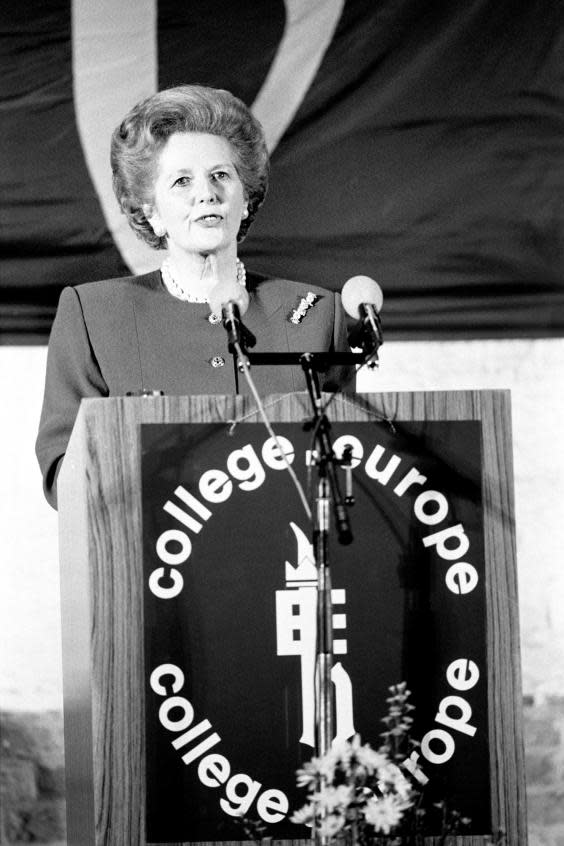

In 1988 Margaret Thatcher addressed the College of Europe in Bruges. She provided several guiding principles for the EEC, and argued that “willing and active co-operation between independent sovereign states is the best way to build a successful European Community”.

This encompassed Britain’s vision of an intergovernmental organisation in which member states retained sovereignty, markets were opened up and regulation decreased.

These ideas were shared by both John Major and Tony Blair who both bought into the European project in this way. Successive British leaders were incredibly successful in shaping the union to back this preference and recent academic analysis has found that the decision making process in the EU is best characterised by a “new intergovernmentalism”, in line with Brittan’s vision.

Influence in terms of shaping the direction of the EU is of course a difficult concept to measure but there has been some academic work focusing on this subject. Robert Thomson analysed 125 pieces of legislation that were passed by the EU in a 12-year period starting in 1996. He looked at the preferences of member states on each issue, the initial status quo and the final outcome.

The results provide an indication of how much a member state opposed a policy, which was then adjusted to include the saliency of the member state. Upon doing so a metric was formed to determine which nations were influential. The results are astonishing and show the UK’s preference and initial positions were often extremely close to the final outcome.

Academics Daniel Naurin and Rutger Lindahl wanted to examine this concept further and analysed the contact patterns among European officials. In their study they found that when there was no consensus on issues, member states were most likely to work with UK officials to reach an end solution. This is primarily because British officials are considered to have greater knowledge in complex policy areas and have the ability to act as brokers during negotiations.

Through Britain’s ability to influence and the strength of its negotiating, the UK has been able to pull outcomes towards its own preferences, ensuring the EU pushed in the direction that was preferable to Britain’s wishes.

As time went on the UK’s stature on the European stage grew. John Major noted: “Britain didn’t just want to join the train. It wanted to be in the driver’s cabin.” This was seen in arguably one of the most important developments on the continent: the creation of the single market. No member state pushed more for the single market than the UK, which is evident in Thatcher’s memoirs.

She says it was her “one overriding positive goal” and that she was happy to make a number of concessions, including more majority voting and transferring power to the European Commission, to ensure its creation. Thatcher’s work proved to be influential and the market was founded through deregulation and the removal of barriers, as opposed to through introduction of new regulations, which is what many of the other European nations had pushed for.

This shaped how the single market operated, with liberal economic policies similar to those adopted by the Conservatives and New Labour governments in the UK being at the forefront. This suited the British economic model and ensured British business was amongst the leaders in capitalising on the new market.

It’s not just the single market where the UK had significant influence as an EU member. Tony Blair committed the UK to be at the core of the European Security and Defence Policy and also promoted the eastward expansion of the EU in the hope it would offset the UK’s absence from monetary union. Blair was a proud Europhile but was acutely aware that the British public was not as pro-Europe as he was.

On a number of occasions Britain took a step back, allowing Europe to integrate further without causing disruption, most notably through the formation of the single currency, the euro. It was not just under Blair that this tactic of taking a step back took place: in 1993, before Blair became Labour leader, the EU was under significant strain as the exchange rate collapsed.

The UK understood that although it was not directly affected by the crisis, it had a vested interest in ensuring that its primary trading partners did not face economic and political difficulty. Britain proposed relaxing the mechanism without abandoning it and threatening the monetary union.

The move saved the EU from what could have been a huge disaster and kept afloat the integration project – one in which the UK had declined to participate.

It was similar to the role the UK played during the eurozone crisis. Policies such as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which helped to address the sovereign-debt crisis, got crucial support from the UK, and this proved to be essential in ensuring the bloc did not crumble under the pressure of a significant crisis. The UK was happy for other European nations to integrate further and even offered a helping hand when it was required.

Brexit and British influence

In 2016 Britain voted to become the first member state to vote to leave the European Union. If a country was ever destined to leave, Britain was it, given its turbulent relationship with the continent.

Even as Britain bids farewell, it once again proves its importance, shining a light on many of the flaws of the European project on the way out.

Brexit not only provides the opportunity for the EU to consider why a member state left and address what some view as errors in its design; it also highlights the significant gap left after an influential member state walks away.

Putting the obvious financial implications that the EU faces of losing one of its largest net contributors aside, on a political level the UK’s work will be missed. Britain currently has 73 seats in the European parliament, the third highest delegation behind Germany and France and level with Italy. British MEPs have made significant contributions to the parliament over the years and the UK’s work will have to be replaced.

The European parliament has several committees that manage the progress of legislative bills. These committees often appoint a rapporteur to write reports on the bills and also lead the negotiations for it to be passed.

Post-Brexit, the EU will change, serving as a reminder of how Britain helped to maintain a careful balance in the bloc

Rapporteur positions are considered powerful and can shape and influence law. British MEPs are incredibly influential in this area and have held rapporteur positions on more dossiers than representatives from any other member state bar Germany.

Britain’s 73 seats in the European parliament will have to be redistributed. Despite a new formula for seats being agreed ahead of the 2019 European elections, the UK’s departure opens the doors for negotiations from all member states to determine what happens to the UK’s quota.

Academic Jonathan Rodden argues that during the bargaining process states that may lose out in terms of representation may need to be compensated with other payoffs. Given the complexity of finalising any agreement, which must be proposed by the European parliament, then unanimously agreed upon by the European Council, voted on by the European parliament and then ratified by each member state, full support for the proposals will be required and the negotiations could therefore change several aspects of the EU in the process.

Post-Brexit, the EU will change, serving as a reminder of how Britain helped to maintain a careful balance in the bloc.

Conclusion

Britain has had a substantial impact on Europe since 1945. The UK’s influence in the creation of the intergovernmental organisations of the OECC and Nato demonstrated its ability to shape the security, prosperity and co-operation of the continent, and the UK proved throughout this period that it mattered and had the ability to determine the direction of European integration.

Inside the EEC/EU Britain was able to influence multiple policy areas, most notably the creation of the single market. When Britain did not wish to partake in further integration it allowed other European nations to proceed with their plans while taking the lead in other policy areas.

As Britain now leaves the EU, several questions arise about how the EU will manage the loss of one of its largest nations.

It is therefore apparent that in the three distinct eras – before joining the EEC, being a member of the EEC/EU and now leaving the EU – Britain has mattered to Europe. Although the focus is now purely on the future relationship with the UK and Europe, we should not forget the role Britain has placed in shaping European geopolitics in the past 75 years.