Should we bring back the woolly mammoth? SXSW experts talk ethics behind de-extinction

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Bringing back long extinct animals, including the woolly mammoth, to once again roam the Earth might sound like the newest "Jurassic Park" movie, but it’s very much reality.

While we can’t bring dinosaurs back because their DNA is too old to be properly sequenced, scientists are working to bring back specimens including the woolly mammoth and dodo bird and have successfully restored some plants already, including the American chestnut tree.

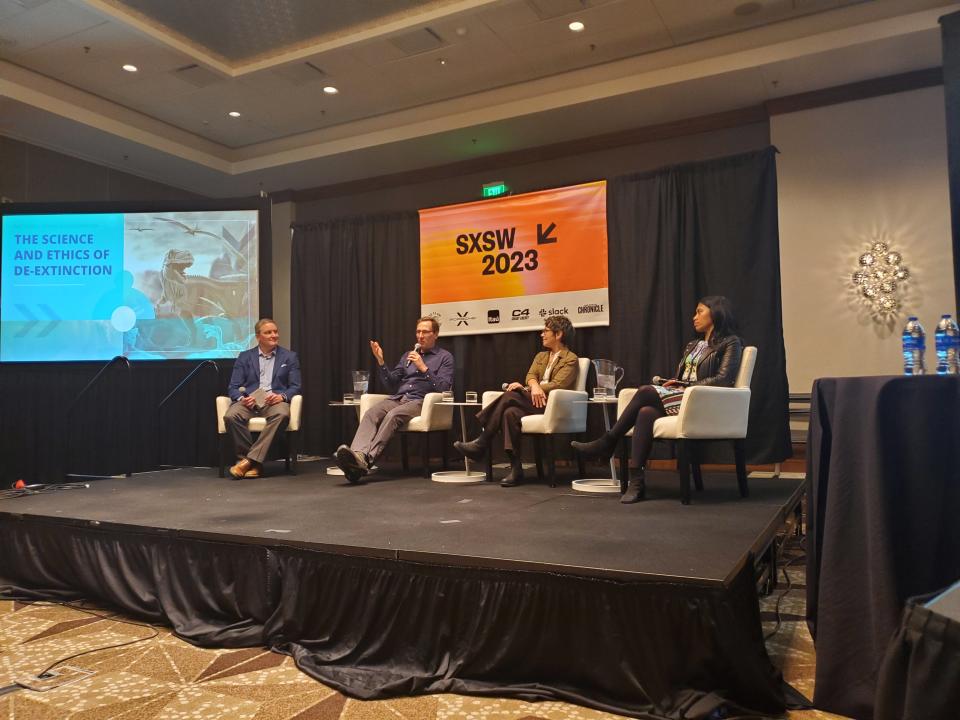

Experts at South by Southwest spoke about the very real reality of de-extinction, or the process of bringing once extinct animals — or at least a close version of them — back to life. The scientists and industry experts discussed the process and progress of de-extinction technology, as well as the ethics of bringing animals and plants back in two different sessions.

How does de-extinction work?

Typically, when scientists look to bring back an animal or plant, it will not be exactly the same as its ancestors. Instead, scientists usually are looking to create a hybrid animal, crossed between the extinct animal and its closest living relative, that selects the specific traits most commonly associated with the animal and its ability to live in its natural environment.

During a SXSW session on de-extinction ethics, Beth Shapiro, a biologist at the University of California at Santa Cruz, said that while most people may think of cloning when they hear de-extinction, to clone something you need a living cell. Once an organism dies, there are no more living cells and any DNA that is there starts getting broken down by processes and elements such as UV radiation, freezing, thawing and fungi. For that reason, most de-extinction is focused on the DNA we can find, primarily in animals that died in the past 50,000 years such as mammoths, though the oldest DNA recovered from a bone is 1 million to 2 million years old.

To bring an animal back, scientists need to collect DNA from ground-up bones and sequence them. The scientists then compare the genes to the animal’s closest living relatives and count the number of differences. From there they figure out what they want to change and gradually tweak the genetic sequence. Once scientists do have a gene sequence in cell form, they can use cloning to swap for an edited cell.

The genetic differences between an extinct animal’s genes and its closest relatives' can be in the hundreds of millions.

“We can’t actually create something that's identical,” Shapiro said, explaining that even if we somehow could change all the genes in DNA to be the same, other factors such as gestation period and environment also can lead to changes.

But scientists are generally looking to change traits that will most make an animal like its ancient relative. With a wooly mammoth, for example, the change would include editing back cold-tolerant genes and shaggy hair. Bringing an animal back also can mean rewilding it, or putting it back in its original environment, so a de-extinct animal ideally fills the niche it once did.

“It’s resurrecting some traits, some physical attributes to fill the niche of that animal,” Shapiro said. “De-extinction is not a solution to the extinction crisis but can help fill the environments in which we live.”

De-extinction can also be done for plants. Jason Delborne, a professor at North Carolina State University, has been part of the efforts to bring back the American chestnut tree, which was important to Native Americans and colonial America, but died off in the late 1800s because of a fungus. Scientists have been working to bring back a functional version of the tree that would be resistant to the fungus.

How is Texas involved?

One of the best known companies involved in de-extinction work is Texas-based Colossal, which was co-founded by Austin entrepreneur Ben Lamm and geneticist George Church of Harvard Medical School. It formed in 2021 with the goal of advancing the field of de-extinction and combating climate change. The company is best known for its work to bring back the wooly mammoth and has also been working to bring back the dodo bird and the thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger.

Lamm discussed de-extinction during a featured session, where he explained the company's efforts, and how it fits into conservation.

"I don't think that Colossal is the solution to the biodiversity crisis," Lamm said. "I think that Colossal is bringing attention to the biodiversity crisis and developing tools."

More:Could Austin entrepreneur's company help bring back the woolly mammoth?

What are the ethics?

The ethics of bringing back extinct animals has been a hot topic among scientists and people following de-exinction efforts. Delborne, a social scientist, said it's important to have conversations about who decides what gets brought back and why, and added there is no one right answer.

"One of the main arguments is we broke it so we should fix it," Delborne said about de-extinction in general. "We have a responsibility to restore because we are responsible for its functional extinction."

Lamm said that Colossal has only announced animals it thinks would be beneficial to restore the ecosystem, and that likely had a human hand involved in their extinction.

"We had this goal of what can we do, what should we do, and why should we do it? We eradicated the dodo, we eradicated the thylacine. Lots of paper suggest we had a hand in the eradications of mammoths," Lamm said.

Mairin Balisi, a curator at the Alf Museum of Paleontology in California and who studies mammalian carnivores, said there is evidence that modern animals are filling some niches, and said scientists have to consider their goals when rewilding animals.

"Do we want to bring the animals back or their ecological functions? There’s some evidence we may not have to bring the animals back," Balisi said.

For example, she has had discussions on whether we would need to bring back a saber-toothed cat when mountain lions exist in the ecosystem.

Lamm's biotech company's launch has been particularly controversial because it may be the first startup in the space, and Lamm acknowledged the company is not perfect. He said the company is working with indigenous groups, private landowners, state and federal governments and others ahead of rewilding any animals, and working on educating the public.

"We haven't done everything right, Lamm said, but I think the more transparent and receptive we are to feedback, the better. We've got to be a good steward."

Some also view the company as taking money away from conservation research, but both Lamm and Shapiro, who works on the company's dodo efforts, say the money is largely tech money that would not have been going toward conservation. They said the company is also developing important tools to aid in conservation efforts.

"We have to be careful that we're not so scared of taking risks that we take the tremendous risk of not allowing ourselves to explore what these new technologies can do." Shapiro said. "Not doing it because we're scared of it is a tremendously bad idea."

When could we see animals and plants return?

Colossal has been vague on the exact timelines of when it will bring animals back, but Lamm said within a decade for most of its animals.

For woolly mammoths, Lamm said its hybrid could come as soon as 2028.

"I think it's a realistic goal based on where we are today," Lamm said, noting elephants have a 22-month gestation period. Other animals, while presenting their own challenges, have shorter gestation periods that could help speed up the process.

Whether or not the American chestnut tree is allowed to be planted anywhere is still up for debate. Its future is also being discussed by scientists and groups such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration.

"It has been recommended for deregulation. Likely the U.S. government will let us plant the trees wherever we want soon," Delborne said.

More:Can a Texas company bring back the long-extinct dodo bird?

More:From mammoths to software: Texas biotech company Colossal spins off new venture

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Deextinction of the woolly mammoth? SXSW experts talk process, ethics