Bringing back the giants: Tennessee's intergenerational sturgeon restoration project

It’s an overcast December morning. Dave Matthews, a fisheries biologist for the Tennessee Valley Authority, is getting ready to launch a boat from Kingston City Park into Watts Bar Lake.

“Every year we wait for it to get cold and miserable to go find them,” Matthews smiles, gesturing out over the water. He’s bundled up, prepared for a long day.

For the past 20 years, Matthews and his colleagues have surveyed the Tennessee River system in one of the most ambitious conservation projects in the country. Their mission is to reintroduce lake sturgeon to the Tennessee River.

“They are from here," said Matthews. "And we believe they should be here."

We are just downstream of the confluence of the Emory and Clinch rivers. But it’s shallow here. Wading birds like egrets and herons patrol the glassy water. It’s a major intersection — a fish highway of sorts. The perfect place to for Matthews to sample.

A multidecade project

Since 2000, Matthews has been part of the Tennessee Sturgeon Working Group, a coalition of over a dozen research and conservation agencies including TVA, the Tennessee Aquarium, the University of Tennessee, Wisconsin and Tennessee conservation agencies and the federal Fish and Wildlife Service.

The group has stocked over 250,000 young sturgeon in the Holston, French Broad and upper Tennessee rivers over the past decade.

“If it was just the TVA, we couldn’t do this ourselves,” said Matthews. “We have to have everybody.”

The project began as a little experiment. Matthews and a colleague of his, the now-retired Charlie Saylor, discussed releasing sturgeon in 1992. They got a hold of 3,500 fertilized eggs and released hatchlings into the river. Years later when they started to actually see young sturgeon, they realized that a coordinated effort might be able to bring back the ancient fish. Sturgeon stocking began in earnest around the year 2000.

The process of restoring sturgeon is a bit like restoring old-growth forest. They take decades to grow. But unlike trees, the sturgeon migrate. Tracking their growth means catching, tagging and genetically testing hundreds of fish over hundreds of miles for 50 years or more.

Now, as the project hits the 20-year mark, scientists are eagerly watching for the first signs of sturgeon spawning. Male lake sturgeon begin breeding early in life, between the ages of 8 and 12 years old. In contrast, female lake sturgeon reach sexual maturity later. The majority begin breeding between 24 to 26 years of age, though some begin earlier.

If sturgeon begin breeding in the Tennessee River, it will be one of the most successful conservation projects in North America.

“We know they’re surviving,” said Matthews, carefully wrapping a line of hooks. “The big question is will they reproduce now?”

A fish older than fur

Sturgeon are among the most ancient living fish on the planet. As a group they both predated and outlived many dinosaur species, including Tyrannosaurus rex. Fossil sturgeon have been dated to 200 million years ago, around the end of the Triassic Period. Twenty-seven sturgeon species swim the earth’s waters today.

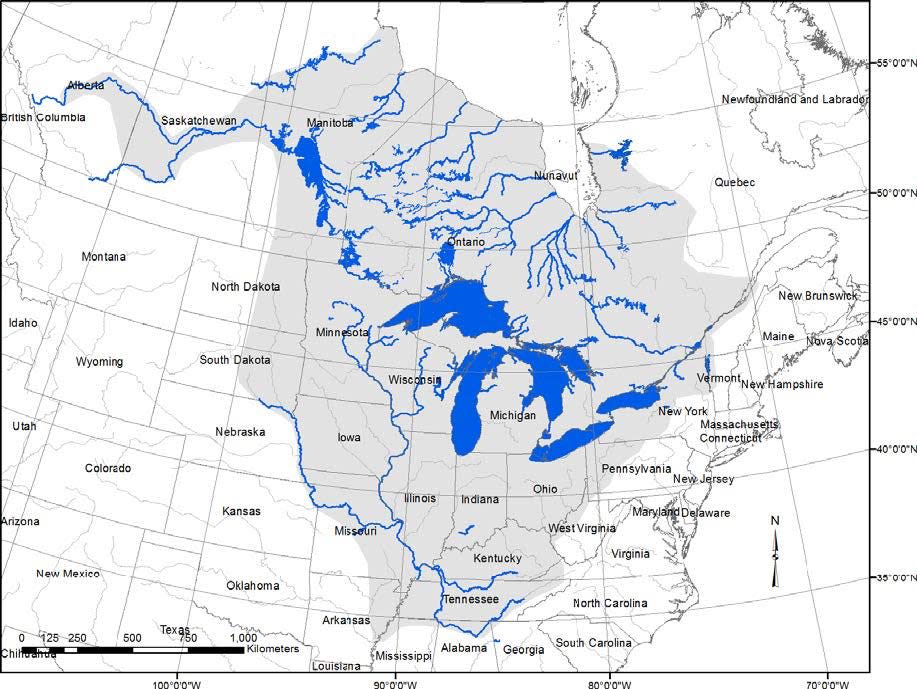

Lake sturgeon split from their closest relatives in North America between 65 and 95 million years ago. Over the ensuing millions of years, they spread through the entire Mississippi River system, into the Great Lakes and as far northwest as North Saskatchewan river in Alberta, Canada, over 350 miles north of the border. They hopped watersheds as glaciers retreated, temporarily linking river systems with enormous glacial lakes.

They grow to enormous sizes, up to 8 feet long and 300 pounds, beyond the reach of nonhuman predators. And like gentle giants of the sea, the lake sturgeon is relatively harmless. They graze on small, bottom-dwelling invertebrates, catching fish only incidentally as they vacuum up insect larvae with their rubbery prehensile lips.

Sturgeon rely on smell and electroception to find food. They feel the bioelectric pulses of living things in the muddy dark, searching for tiny glimmers of life in the cold.

These slow-growing, long-lived fish migrate hundreds of miles during their lives to feed, to grow and to spawn. Matthews told Knox News that sturgeon released as part of the stocking program had been found in Guntersville, Alabama, roughly 300 miles away as the fish swims.

Clear-cutting an old-growth fish

But all the things that make lake sturgeon remarkable like their long lives, slow growth and wanderlust, make the fish vulnerable to extinction. Sturgeon habitat ranges were cut by the damming of rivers by organizations like the TVA and Army Corps of Engineers. Silty runoff from clearcutting choked the streams of spawning sites.

Overfishing for meat and caviar crashed the population. In the Tennessee River system, commercial sturgeon harvests began in 1956. By 1961, there were no reports of sturgeon harvests and few incidental captures or sightings, presumably because they were fished out.

More: Kelley's Katch: How a Tennessee company became a top caviar producer

“But it wasn’t just caviar. If you’re living in an impoverished valley … you catch a fish like that and you feed your family for a long time,” said Matthews.

But overfishing hurts in the long run. Sturgeon take 20 years to grow to a decent size and they don’t spawn every year. On any given year, roughly a quarter of the adult sturgeon mate. With few healthy adults around plus dams blocking the way and silt in the water, sturgeon could no longer live on the river.

“We human beings made a lot of mistakes, back in the day,” said Matthews. “We didn’t know what we had.”

Currently lake sturgeon occupy roughly 1% of their ancestral range. While they are protected in many states, they lack federal endangered species protection. Lake sturgeon have lingered on the Endangered Species Act waiting list for years. In 2020, a federal court ordered the government to decide if lake sturgeon should be listed as endangered by September 2022.

They disappeared before we knew them

Matthews pulls his boat up to a line. He and his partner struggle. Something large is on the hook. After several minutes of maneuvering and pulling, a sturgeon appears. She’s almost 5 feet long, thrashing as she’s pulled from the water.

Matthews and a fellow biologist maneuver her into a cooler full of oxygenated water to take measurements. She’s heavy, coming in at almost 30 pounds. Matthews gently feels along her sides for a tell-tale mark left behind by the hatchery on the boney armor plates on her flanks. The mark tells him how old she is and when she was released in the river.

“She’s from 2003,” Matthews says to the other biologist. The sturgeon is 18 years old. She’s from the very beginning, within the window to be an early breeder.

The pair take samples of blood and fin tissue for genotyping. A chip is injected just under her skin, so that other scientists in the future will be able to identify her if she’s caught again.

Matthews comments that a lot of these samples, and this tracking, is done to correct a deficit. Sturgeon disappeared from the river before scientists could document their lives.

"We know some of what we're doing is working," he said, referring to the way that TVA had changed its dam flow practices to make the Tennessee River behave more like a river, and less like a series of large lakes. "We're collecting so much data, unfortunately it takes time to analyze that data and figure out what's going on."

Matthews is prepared for the project to outlive him. He jokes that maybe, in 20 years’ time, his successor will wheel him down to the water’s edge to watch a big sturgeon spawning.

In the meantime, Matthews and his colleagues urge people to help them protect the sturgeon. If you see a sturgeon, leave it alone or snap a photo so you can tell the TVA or TWRA where you saw it. If you see someone else bothering a surgeon, Matthews urges you to pick up the phone and call TWRA.

"Once when we were tagging sturgeon a local guide came up to us with his cell phone out yelling 'Hey y'all need to leave those sturgeon alone. I got TWRA on the phone!'" laughed Matthews. "I was like, 'Thank you sir, but so do we.'"

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Sturgeon: Bringing back ancient giants to the Tennessee River