Bringing 'Hamilton' to the screen: Filming is easy, editing's harder

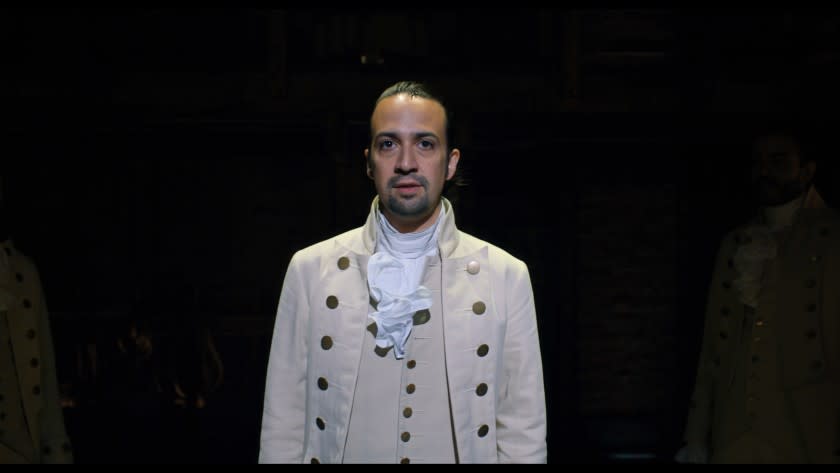

When Lin-Manuel Miranda starred in "Hamilton," his onstage entrance was regularly met with applause. The cheering and clapping was so long and loud that it drowned out most of his opening notes.

"It's not a great start when you can't hear the title character's first couple lines," director Thomas Kail recalled to The Times. "People were applauding not based on that experience of watching the show — it just started, he hadn't even done anything yet — but what he had already done, which is writing it."

The Broadway production put in a pause to accommodate the acclaim; subsequent stagings, regardless of who is playing Hamilton, have followed suit. But the filmed version astutely skips this beat — no pause, no applause per Miranda's request.

"So many people who will be seeing this movie have never seen the show before," Kail said. "We wanted to earn the applause with the story we're telling for this audience."

Kail is referring to those watching the "Hamilton" movie, which hits Disney+ on Friday. The high-priced acquisition is being released on the streaming service amid the closures of the Tony-winning musical's stage productions throughout the world to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus.

None of this could have been foreseen when filming took place in 2016, shortly after the show won 11 Tonys and just before the original Broadway cast was set to disperse. It's uncommon for productions to be filmed for release, especially a phenomenally popular one with a record-setting average ticket price and multiple national tours and open-ended productions.

Fresh from directing Fox's live broadcast of "Grease" and coordinating TV-friendly "Hamilton" performances for various award shows, Kail did not throw away his shot.

"Theater disappears every night after the curtain call, and then you have to go and make it again," he said. "That's the beauty of it, but that's also the challenge. There was something about this moment where we thought, 'No matter when this comes out, let's honor and preserve the moment we have with this extraordinary cast, assembled all in the same place at the same time.'"

Nine cameras were placed throughout the Richard Rodgers Theatre (including overhead and from the rear of the stage) to ensure coverage of the show's 10 principal actors and 11 ensemble members, who freely roam (in deliberately choreographed fashion) the two-story set. Two full performances were recorded with ticket-holders in tow; 13 audience-less numbers were captured via Steadicam, crane and dolly between ticketed dates. Each recording includes individual audio tracks from the microphones of each actor and orchestra instrumentalist. (The drum kit alone had seven separate mics.)

Filming is easy, Kail learned; editing's harder. Especially without a hard deadline from a studio, and at a time when the director was pursuing other projects. He worked with editor Jonah Moran on a first pass at the end of 2016 and, after directing numerous off-Broadway plays, finished another cut in 2018. Earlier this year, he and Moran revisited the footage for the first time in 18 months and added what Kail called "the more stylized moments that are now in the film," which the two dreamed up after collaborating on FX's "Fosse/Verdon."

What results is something that exists between the mediums of film and theater, yet fundamentally resembles a broadcast of a sports game. Thanks to all the visual access, the view is arguably better from the comfort of your home than from any seat in the venue.

The camera often dances onstage, close enough to the actors to catch the sweat on George Washington's (Christopher Jackson) head and the spittle dripping from King George III's (Jonathan Groff) mouth. It captures Eliza Schuyler's (Phillipa Soo) intimate feelings when she's both madly in love and overcome with heartbreak, and Aaron Burr's (Leslie Odom Jr.) vexed expressions whenever he's in Hamilton's shadow.

"No one was 'turning it on' for the cameras," Kail said of filming the cast. "This is exactly the same performance they were all giving people every single night. It was always that remarkable and it was always that true."

Like televised games, this "Hamilton" movie has a layer of commentary that live audiences don't and won't ever get. For example, one frame in "The Room Where It Happens," in which Aaron Burr laments of being sidelined in political proceedings, puts him in soft focus between decision-makers Thomas Jefferson (Diggs) and James Madison (Okieriete Onaodowan), both crisp and positioned like giants in comparison to Burr.

"I was so moved by what Tommy made because, in theater, it's all a wide shot," Odom said. "Film is a director's medium; he chooses where to focus our eye on this performance we all did four years ago. Watching it, I was out-of-body a little bit, seeing myself in this role for the first time."

Yet many of the standout shots simply encapsulate the groundbreaking creations that were not included in the cast album. Even the most seasoned listeners will be surprised by three musical moments that weren't aurally recorded. They'll experience Howell Binkley's targeted lighting design, often only spottable when seated in the mezzanine. They'll see all the visual humor, mostly delivered by Daveed Diggs in his dual role as the Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson. Each shrugged-off punchline is met with audience laughter, caught with mics installed throughout the house just for the recording.

"We all wanted to capture the spirit of the expression of the piece as it happens, live, in the room," said Nevin Steinberg, the show's sound designer who consulted on the movie's sound design. "Getting the right mix of audience reaction is part of that."

Viewers will also meet the unsung heroes of all Broadway musicals: the ensemble. In "Hamilton," they're at times physically expressing a character's true feelings or projecting the voice of the masses; other times, they're simulating a powerful hurricane, dreamlike time travel or a deadly bullet.

"Movie audiences aren't used to an ensemble of actors becoming stories in an abstract way," said choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler. "And a lot of times, the tendency of these theatrical captures is to go close to the principal [actor] all the time, and the audience misses so much. The physicality in the show adds levels of complexity to the subtext, and I think this film does a great job of representing that."

Still, if "Hamilton" is not as good as when you saw it live, well, that's because you saw it live. Any sports fan will tell you that being in the room where the buzzer beater happens always adds a layer of excitement you can't get watching at home.

This movie is not, and will never be, the performance itself. It is only a version of it, deliverable to at-home audiences in a visual language they recognize. And according to Kail, the world is wide enough for both "Hamilton" the stage musical and "Hamilton" the film, without one cannibalizing the other.

"When we all feel safe to go back and watch live performances, this will live alongside of it," he explained. "It's a companion in the same way that almost every show on Broadway has a cast album, which I think has only enhanced people's experience and connections to their favorite shows.

"I hope it will infuse a new generation of theatergoers, people who see this and had never seen a show before or thought that musicals were for them," he continued. "Perhaps it'll make someone want to write a musical or subscribe to the touring house within their city. Maybe it makes you want to go in the dark with a bunch of strangers and watch a story be told — what people have been doing in the theater for thousands of years.

"We're gonna need that when we're all up and running again."