Broadway star wed NC millionaire 90 years ago today — then was accused of his murder

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

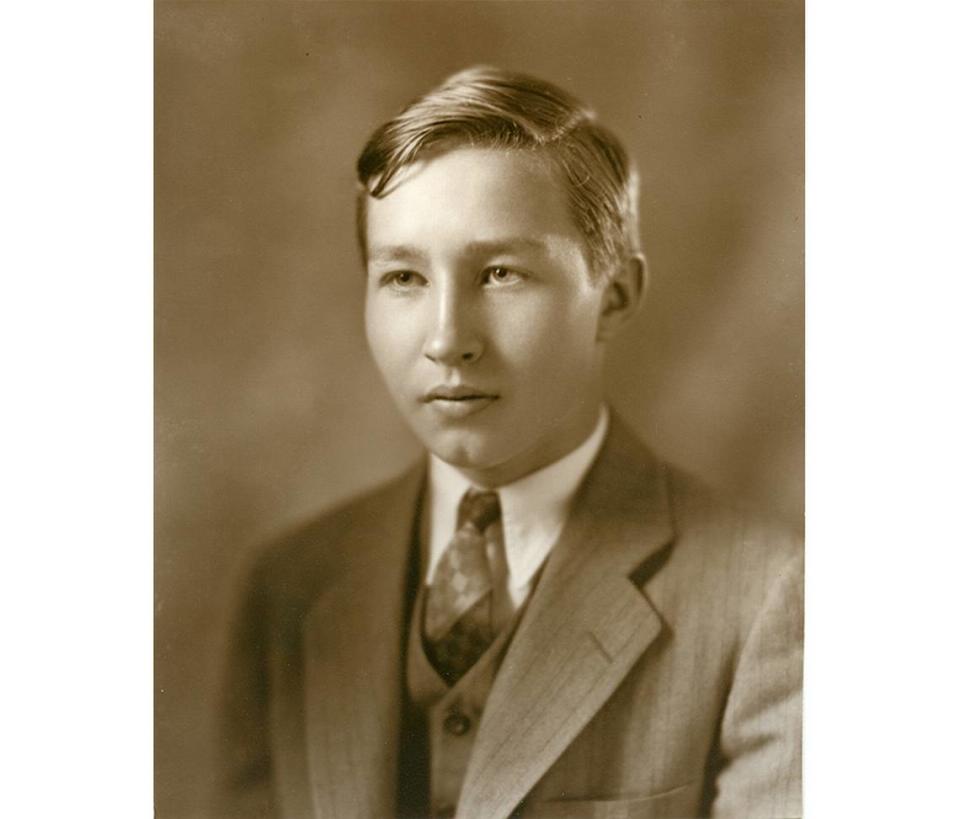

Z. Smith Reynolds was divorced for just six days before he remarried in a secret courthouse ceremony on Nov. 29, 1931.

The bride was 27-year-old Broadway star Libby Holman. Reynolds, who went by “Smith,” was 20 years old and the youngest heir to the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco fortune in North Carolina. He stood to inherit $20 million on his 28th birthday, according to newspaper accounts.

But less than a year after their secret nuptials — and only a few months after announcing the marriage publicly — Reynolds died from a gunshot wound to the head at the family estate in Winston-Salem.

Holman and Reynolds’ best friend, Albert “Ab” Walker, were accused of murdering him.

Holman was 5 foot 6 inches and 124 pounds with “an ample, almost buxom figure,” Vanity Fair reported in 1985. She came to New York from Ohio and rose to stardom on Broadway, becoming well known as a so-called torch singer, belting out love ballads.

She met Reynolds in 1930, a time when he was receiving an allowance of $50,000 a year before his inheritance kicked in at 28, according to Vanity Fair. That’s the equivalent of roughly $808,000 today.

Holman was touring when Reynolds became smitten with her, sending “flowers and notes to Libby’s dressing room nightly,” Vanity Fair reported. He followed her to Europe and back, called often and proposed marriage.

Reynolds, however, already had a wife, Anne Cannon, “whose father was to towels what R.J. Reynolds had been to cigarettes,” the Winston-Salem Journal reported in 2007.

Reynolds was “barely 18” when he wed his first wife, according to the newspaper, and they had a daughter together before the marriage collapsed. Holman finally agreed to marry Reynolds, and Cannon divorced him in Reno, Nevada, in 1931, on the grounds of cruelty, the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources said.

Six days later, Reynolds and Holman got married in Monroe, Michigan — a fact she would later testify to during an inquiry into his death, The New York Times reported. The world wouldn’t know about their nuptials for another six months.

Suicide or murder?

The New York Times broke the news of their marriage in May 1932, and the couple moved to the Reynolds family estate in Winston-Salem — known as the Reynolda House — in June, according to the Winston-Salem Journal. They hosted lavish parties in the 60-room house despite the constraints of Prohibition and the Great Depression.

One such party was held on July 5, 1932. The guests spent much of the night drinking bootleg alcohol before wandering home around midnight, the Winston-Salem Journal reported. Reynold’s friend Walker would later testify that he was closing up the house around 1 a.m. when he heard a gunshot. Holman reportedly shouted from the second floor that her husband had shot himself.

According to a 1987 Greensboro News & Record article, the couple had been in the second-floor master bedroom and engaged in a “jealous argument” when the gunshot rang out. Some reports suggest Reynolds may have been on the sleeping porch adjacent to the bedroom at the time.

Holman and Walker drove Reynolds to the hospital, where he was declared dead the morning of July 6, 1932, the New York Times reported.

A headline in the New York Times the morning of his death read “R.J. Reynolds Heir Commits Suicide,” followed by a subhead that stated, “Relatives Are Mystified.” The article referenced Forsyth County Coroner Dr. W.N. Dalton, who declared the death a suicide. The county sheriff, however, was still investigating.

“The sheriff said he found an apparent conflict in Mrs. Reynolds’ statements,” the Times reported. “She told him, he said, that she was on the sleeping porch when her husband shot himself, but was not clear as to whether or not she saw him do it.”

Reynolds’ uncle, James S. Dunn, acting as spokesperson for the family, told the Times “he was at a loss to find any cause for suicide.”

“He stated that Smith was in high spirits during the past few days and seemed intensely interested in his plans for the future,” the Times reported.

A coroner’s inquest was subsequently called to determine the cause of death.

‘I felt his blood’

Holman testified during the inquest and told the jury about her short-lived romance with Reynolds, the Winston-Salem Journal reported.

“I would not have married him at all because he was so young, but he appealed to me so,” she reportedly told the inquest’s jury. “He begged me so, saying, ‘I need you now. I need someone. I never had any love in my life. I must have you. I am so lonely. Please.’”

At one point during the nearly two-hour testimony, the Journal reported, Holman said her husband suffered from “male virility problems” and begged her to have an affair. Later, she admitted to being pregnant.

Holman also said she had no memory as to what happened on the night of Reynolds’ death, short of seeing the pistol at his head, according to the 1987 Greensboro News & Record article. When the prosecutor questioned whether she remembered anything after that, Holman said no.

“Nothing. I have this feeling that Smitty was in my arms and I felt his blood,” Holman reportedly said. “But it is a haze... it is blurred.”

After a three-day inquest that began July 8, 1932, the coroner’s jury determined Reynolds died “at the hands of a person or persons unknown,” the New York Times reported. The case then went to a grand jury, which indicted Holman and Reynolds’ boyhood friend, Walker, on murder charges on Aug. 4, 1932.

Walker was arrested that afternoon, but Holman’s whereabouts remained unknown until she turned herself in four days later on Aug. 8, The Greensboro News & Record reported in 1992.

Holman appeared before a judge in the small town of Wentworth, in Rockingham County, North Carolina, which had about 100 residents at the time. According to the newspaper, the community was besieged by reporters and spectators for the event.

Holman arrived in a black limousine, shrouded behind a black veil, The News & Record reported. But she was never handcuffed nor were any deputies assigned to guard her.

The judge set Holman’s bond at $25,000 and let her sign the papers in his chair before she went back to a hotel in Reidsville, according to the newspaper. Holman left in the middle of the night, never to return to the area.

A life of tragedy

Prosecutors eventually dropped the murder charges. According to The News & Record’s 1987 account, that decision might have been motivated by a “legal situation” involving Holman’s pregnancy and Reynolds’ inheritance — a court battle the “scandal-dreading Reynolds family” reportedly hoped to avoid.

Several months after the charges were dropped, Holman gave birth to a boy named Christopher Smith Reynolds on Jan. 10, 1933, according to Vanity Fair.

She was awarded $750,000 from her late husband’s estate, and her son inherited $6.25 million, Vanity Fair reported. His family used much of what remained to start the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, which has endowed a number of “eclectic” causes over the years — including fighting venereal diseases in North Carolina, The News & Record reported.

But life’s tragedies for Holman didn’t end with Reynolds’ death.

Her son Christopher, who she called “Topper,” died from a fall at age 17 in June 1950 while trying to climb Mount Whitney in California, Vanity Fair reported.

More than two decades later, Holman died by suicide from carbon monoxide poisoning in the front seat of her Rolls Royce. She was 67.

Gangster rivaling Al Capone arranged infamous Charlotte heist on this day 88 years ago

Conjoined twins from NC who escaped slavery, performed for royalty died 109 years ago

From ‘Human Spider’ to highest-paid Santa: This daredevil from NC would be 125 today