A brother's promise: RI WWII POW's remains coming home - thanks to his brother's DNA

PAWTUCKET – Before Katherine McConnell was buried in the family plot at Mount St. Mary’s Cemetery in 1973, she exacted a promise from her only surviving son, John: Do your best to get your brother Henry's body home, so he can rest beside me.

His brother, Henry McConnell, had been dead 31 years by then, an Army Air Corps private who died at 28 with thousands of other prisoners in the Philippines during World War II. He had been buried initially in a mass grave outside a Japanese prison camp.

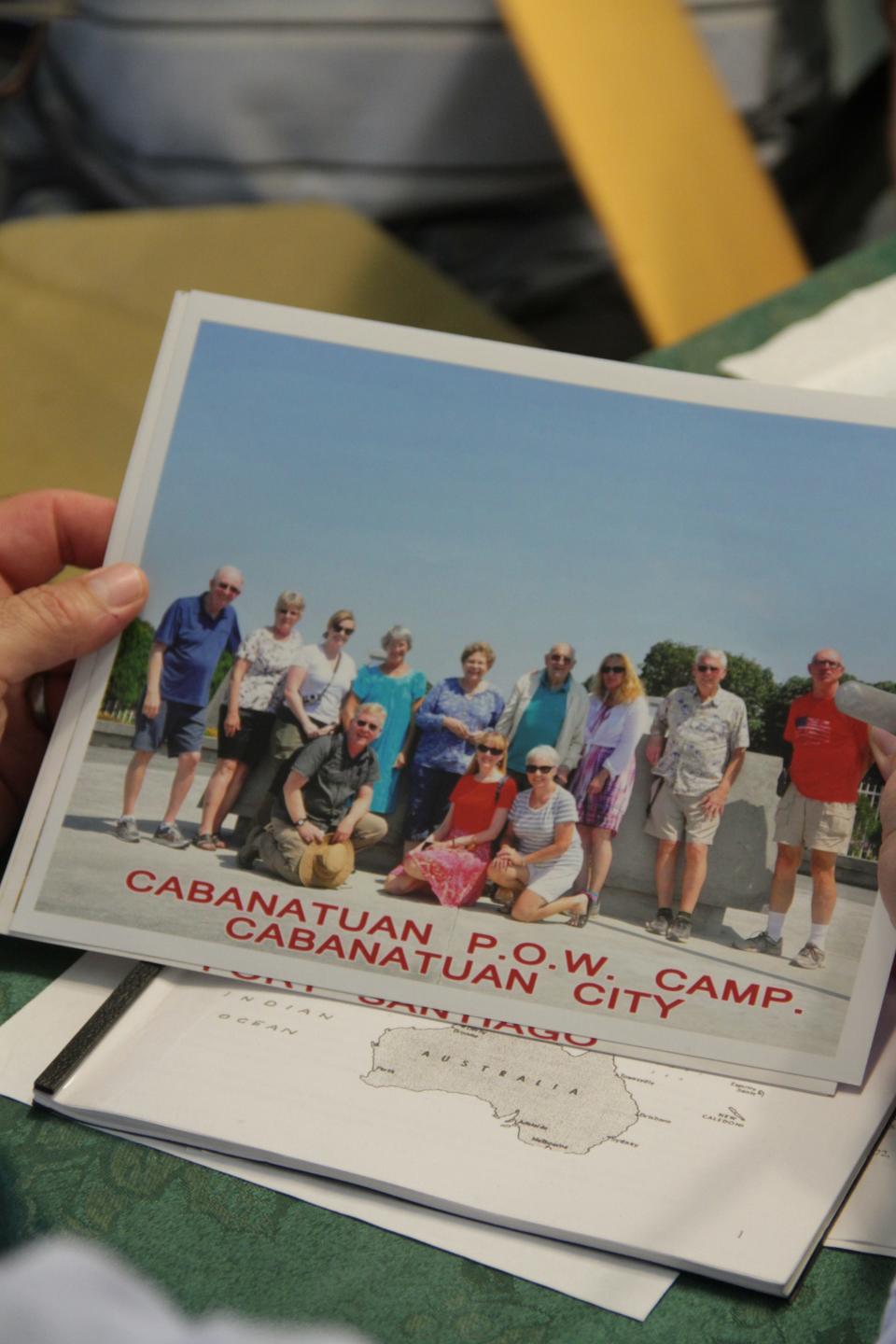

“She sort of put the pressure on me that if I lived long enough, maybe I could claim his remains,” John McConnell told The Journal in a 2015 interview. He was 91 then and recently back from a trip to Manila, where he tried to touch his brother’s engraved name on a monument to the missing. It proved out of reach.

On Thursday, Nov. 30, Henry McConnell’s remains will be laid to rest in the McConnell family plot with full military honors.

John McConnell did not live long enough to see the day come – 80 years after his brother's death.

But it was his DNA, offered up years ago, that made identification and his brother's eventual return home possible, says his daughter.

“He made a promise to his mother that he would get his brother home, and he kept it,” says Charleen Primo of Cumberland. “I just wish he was here to see it, but I’m sure he is smiling down from heaven.”

Henry McConnell enlisted looking for adventure

Henry McConnell was an adventurous soul. A graduate of St. Raphael Academy in Pawtucket, he entered the University of Notre Dame around 1932 with plans to major in journalism and write about all the distant places he’d someday visit.

But financial constraints forced him to return a year later to Pawtucket, where he went to work in a wire factory. In his spare time he learned to fly and in 1940 joined the Army Air Corps.

Japan was already at war with China, and Henry saw opportunity. “That war’s going to be a big thing out in the Pacific,” he told his younger brother, “and if I can get out there, maybe I can write about it.”

Henry McConnell was among those reported captured in April 1942 when, after three months without food and water and little military support, thousands of Allied soldiers were forced to surrender on the Bataan peninsula.

In the 1950s, Katherine McConnell received a letter from the U.S. government explaining a major effort underway at several former Japanese prison camps in the Philippines to exhume the remains of thousands of American soldiers and reinter them in Manila, where a 152-acre American cemetery was being readied.

But Henry McConnell remained technically listed as missing, meaning his remains had not been positively identified.

A search for answers about his brother's death

John McConnell’s search to understand the last months of his brother’s imprisoned life became an almost endless obsession, says his daughter, Charleen.

“Sometimes it was aggravating,” she says. “He would read a [war] story with some guy’s name in it, and he would be hunting for him all over the world. This was before the internet, and he would write letters asking if he knew anything about his lost brother.”

More on this story: No surrender

Late in his 80s, John McConnell received declassified documents from the federal agencies charged with resolving questions about missing soldiers from past wars. Among the documents was a report on his brother’s death, compiled from records gathered after the war, including the “death roster” kept at Cabanatuan prison.

There, in black and white, the report described how his brother succumbed to dysentery and malaria on the afternoon of July 26, 1942, in Barracks 2. His body ended up in mass grave No. 225 with about 18 other men.

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, the bodies of Common Grave 225 were disinterred in 2018 from an American cemetery in Manila and again examined for identification where DNA was available.

The DNA John McConnell gave proved he was the sibling of Henry McConnell.

“My father had been trying to get Henry home all his life,” says Charleen Primo. “He got every single one of Henry’s medals that Henry was entitled to and gone to every [veterans] ceremony to represent him.”

In 2016, John McConnell died shortly after attending a memorial service for his brother and others like him at the Veterans Cemetery in Exeter.

“He wasn’t even sick,” says Charleen. “I guess he figured the remains would never be coming home.”

When they lay Henry McConnell to rest next week in the family cemetery plot, his brother, John, will be there by his side again.

Contact Tom Mooney at: tmooney@providencejournal.com

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: A Rhode Island POW's remains return home, thanks to his brother's DNA