This Black fraternity was rejected by Brown University. Now it's celebrating 100 years

More than a century ago, Brown University's Class of 1921 posed – as was tradition – on the steps of the John Carter Brown Library for a photo. Preserved in a yearbook, in the first row, all the way to the right, is the picture's only Black face: Jay Mayo Williams.

Williams stood confidently yet casually, one hand in his pocket, looking at the camera with a slight smile. By then, the Arkansas native had become a football star on his way to becoming one of the first Black athletes in the National Football League.

He was nicknamed "Ink." Some say it's because when he became a talent scout for record labels – a career that would surpass his achievements on the field – he had a way of getting performers to sign contracts. Not just any acts, but acts like Ma Rainey. Even Muddy Waters recorded some tracks for Williams.

But that story behind the nickname is likely a work of optimistic fiction. In reality, it probably dates back to his football days and was used as a racial slur.

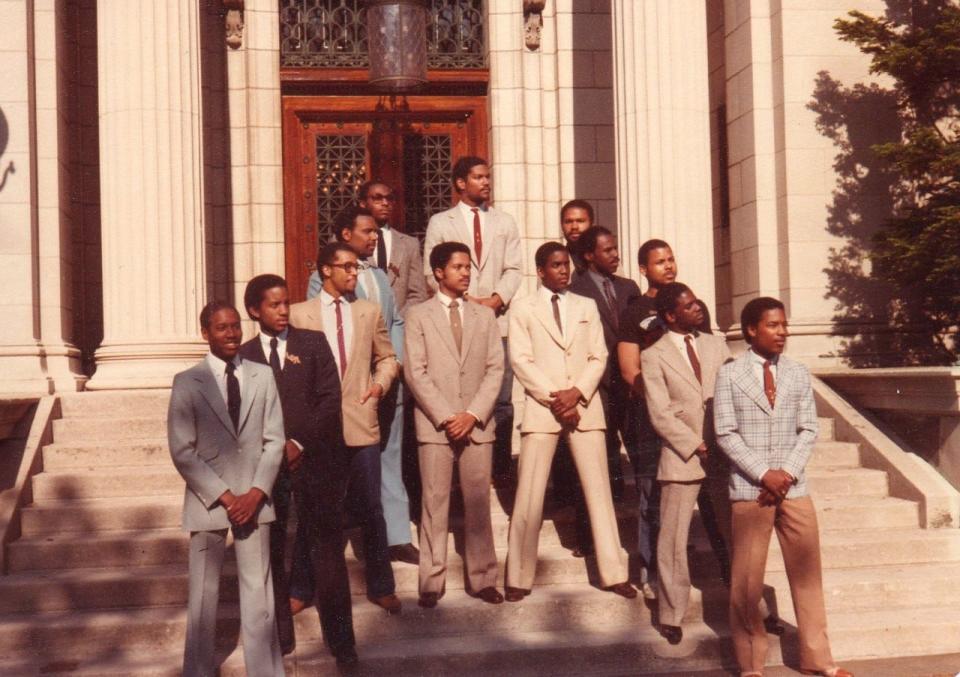

The same year Williams posed for that photo on the library's steps, he was one of 11 students who came together to launch the local chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, the nation's first Black fraternity, established at Cornell University in 1906. Except the Alpha Gamma offshoot didn't receive the same reception at Brown when it approached the dean of students.

'They didn't want any Black fraternities at Brown'

"They said, 'No, you're not approved. There's too many fraternities here at Brown already,"' chapter historian Rodney Robinson said. "And we take that to mean that they didn't want any Black fraternities at Brown."

That wasn't all. Brown also rejected the establishment of Jewish and Italian fraternities. But the 11 students of Alpha Gamma persevered, deciding Providence, not Brown, would be the chapter seat.

"That was really, really important," Robinson said. "Because we've always been a Providence-based chapter, and we were kind of spawned out of rejection and adversity that Brown didn’t want us."

Now, the 102-year-old chapter is finally ringing in its centennial, a celebration delayed by COVID-19.

Examining history: Brown University releases new edition of report examining its ties to slavery

All this time, despite attempts at reflection and atonement through actions such as its Slavery & Justice reports and an on-campus monument to the slave trade, Brown never apologized for its more recent sin. But it did formally recognize the fraternity in 1974.

"I wouldn't say there was an explicit apology," Robinson recalled. "There was not. But Brown did make an acknowledgment to say, 'Here's what history was, and here's Brown's role in that history, and here's where Alpha is today in the community. We thank Alpha for being at Brown and in Providence.' It wasn't about [explicitly saying] 'We're sorry we rejected you.' We were very clear the whole time saying 'you guys didn't want us and and we did it anyway.'"

'Progressive civil war': New front in RI progressive political feud opens as group attacks Regunberg. Here's what they're saying.

A bond of survival

While the typical fraternity may conjure up scenes of wild parties and hazing, Alpha Gamma was born as a brotherhood with a profound mission in a time of struggle.

"The concern was the need for students to come together in a format outside of class so we could establish bonds and kind of survive the racially hostile environment," said Centennial Chair Jamie Ferguson.

Some years ago, Ferguson recalls having a chat with a critic who asked why a Black fraternity was necessary now that the civil-rights movement had come to pass. But Ferguson knows the struggle for equal rights continues.

"What we're seeing is that racism is woven into the fabric of our society, unfortunately," he said. "And we're seeing now we have laws being passed in states to not teach real histories. We're seeing policies that are being put in place to make voting so much harder for people in underserved communities."

PVD's reparations: National model or 'trivialized' budget line that won't create change?

Today, the fraternity continues its deep involvement in the community, with projects such as educational initiatives for students of color, a Black business fair, food distribution at Thanksgiving and support for the John Hope Settlement House that provides before- and after-school programs for kids.

While Alpha Gamma's origins are a clear source of pride for its members, its centennial has Ferguson looking toward the future.

"For us, we can't rely on our history as a foundation or a feeling of satisfaction … We are already here and established," he said. "I think for us, Alpha has to always be changing and developing and ensuring that we are best positioning our initiatives for whatever our communities and whatever people of color will need."

Alpha Gamma's centennial celebration runs from April 20-23, with events at several locations in Providence. For information, visit www.alphas25thhouse.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Brown University's Alpha Gamma fraternity celebrates 100 years