Brown's Haffenreffer Museum is leaving Bristol – and rethinking its role as a modern museum

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

BRISTOL – Decades of East Bay schoolchildren got their first taste of Rhode Island's early history from dusty cases of arrowheads at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, after a long and bumpy bus ride out to the secluded property at the edge of Mount Hope Bay.

But those days came to an end when Brown University stopped offering tours of its facility in 2008, citing "significant fire code and environmental issues."

Now, plans are in the works to move the museum to 1 Davol Square, in the heart of Providence's Jewelry District. Doing so will "open up a host of new possibilities for scholarship, community outreach and partnership with Indigenous communities worldwide," Brown announced in a recent news release.

The move comes at a time when the Haffenreffer Museum, like other anthropology museums across the country, is grappling with its past and rethinking what its role should be today.

As part of that reckoning, curators and consultants are working on returning Native American remains and artifacts to their rightful owners while expanding the museum's collection of contemporary Indigenous art. Recent exhibitions have centered around present-day issues like the Mediterranean migrant crisis and surveillance at Standing Rock.

"The fact that objects leave our collection is not at all a bad thing," director Robert Preucel told The Providence Journal. "It actually helps build relationships with communities. Museums are about relationships more than they are about the objects."

How Brown ended up with an extensive collection of Indigenous artifacts

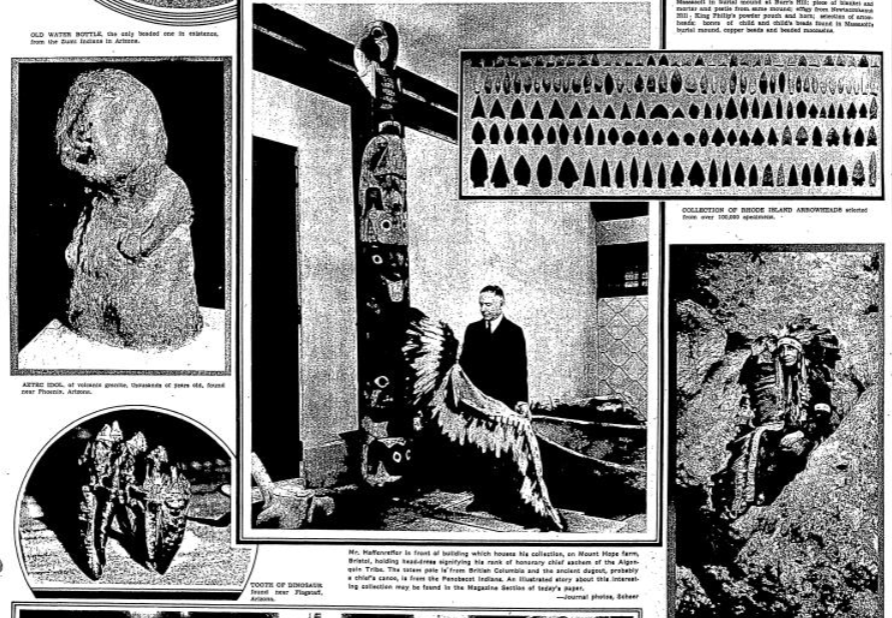

The Haffenreffer Museum started out as the private collection of Rudolf F. Haffenreffer Jr., a turn-of-the-century industrialist best known as the founder of the Old Colony Brewing Company and, later, president of the Narragansett Brewing Company.

The son of a German immigrant, Haffenreffer developed a fascination with Native American archaeology and history and spent several decades traveling around the country to purchase Indigenous artifacts. In 1928, he began inviting members of the public to visit his Bristol summer home and tour what he called "the King Philip Museum."

After Haffenreffer's death in 1954, his heirs donated the museum to Brown University, which expanded its focus to be more global in scope.

"Over time, the collection grew to include objects and art spanning several millennia and six continents," the university's news release says. "Among the items in the collection today are paleolithic hand axes recovered in France, Kiowa and Cheyenne cradleboards, Huni Kuin featherwork from Peru and 1980s Chilean protest art created in response to Augusto Pinochet’s regime."

Today, the idea of a wealthy white man amassing a private collection of Indigenous artifacts would probably raise a few eyebrows. But what Haffenreffer did, Preucel pointed out, was "save some of these objects that would possibly have been destroyed or lost."

Reconsidering the role of an anthropology museum

Today's anthropology museums face a number of questions, Preucel said.

"Can they overcome the stigma of how their collections were acquired and adopt more ethically responsible ways of curating and caring for objects? Can they challenge invidious narratives about civilizational progress, racial hierarchies and cultural superiority by promoting new narratives about community, collaboration and cooperation?"

Part of the museum's role today, he said, is to "help educate the public, our students and faculty about cultural similarities and differences."

Relocating to a diverse city like Providence, he believes, will make the Haffenreffer Museum more accessible – not just to the Brown community, but also to people who come from the cultures represented in its collections.

"We feel we have a special responsibility to those communities," Preucel said.

Why the museum is moving from Bristol to Providence

There's been talk of moving the museum to Providence since at least 1995, Preucel said. In 2005, the museum began holding exhibitions and public programs in a small first-floor space on Brown's campus green.

A few years later, in 2008, the Bristol portion of the museum closed to the public. The university said the aging buildings were not up to date with local fire codes, and that their condition "also made the collections susceptible to inadequate climate control, insect infestations and mold."

Rather than overhaul the facility, Brown said it would move the museum to Providence, citing "the prohibitive estimated cost of remediation to the buildings in Bristol, and the limitations on the usefulness of the collections for teaching and research imposed by their distance from campus."

More: Six years ago, Brown said it would give land back to the Pokanoket Tribe. Where does it stand?

Fifteen years later, the Bristol property still continues to house most of the museum's staff and collections. But Brown says that will be changing soon.

Renovations of One Davol Square, a former mill building that the university has owned since 2007, are scheduled to begin next fall. If all goes according to plan, the museum should be able move to its new home by the end of 2025.

Efforts to return human remains are ongoing

Ahead of the move to Providence, curators have been reevaluating the Haffenreffer Museum's collections and making plans to distribute some items.

For instance, a set of traditional African instruments was donated to the museum but never used because they're a duplicate of other items in the collection. Plans to give them to PVD World Music, an African-centered musical collective, are in the works.

Even before the move was on the horizon, though, the museum began returning human remains and culturally significant artifacts to Native American tribes. To date, the museum has repatriated the remains of two humans, more than 200 funerary objects, and three "objects of cultural patrimony," Preucel said.

Doing so is required under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, also known as NAGPRA, which applies to all institutions that receive federal funding. Preucel said that the process involves consulting with tribes, who review everything in the museum's inventory and "decide what they consider to be sacred or objects of cultural patrimony."

"That's their right to identify any object in the collection," he said.

According to ProPublica's Repatriation Database, the Haffenreffer Museum has made the remains of 12 Native Americans available for return to tribes, but the remains of at least 99 others have not been made available for return. Preucel said that the museum has hired a consulting firm to help with that process.

"We're seeking to repatriate all of the human remains," he said. "It's just a question of staffing."

The future goal: Public gallery space in the Jewelry District

If the Haffenreffer Museum is truly committed to helping tribes reclaim culturally significant items, could it wind up with nothing left in its collections?

"No, no, not at all," Preucel said, noting that the museum has been growing its collection of contemporary Native American art.

"What's interesting is the circulation of objects, how objects come into museums and how they leave, and how that process is actually the process of cultural motion," he said. "We're interested in that. We don't want to just warehouse things and collect things, we want to share things. We want them to circulate."

Eventually, Preucel wants to have public gallery space on the first floor of One Davol Square so the museum can showcase more of its collections.

"Ideally, the exhibits will be produced by our students and our faculty and members of the descendant communities, in conversation with one another," he said.

But that will require additional fundraising. Initially, the Haffenreffer Museum will take up the building's second and third floor, which does not include any designated public space. Exhibitions will continue to take place at Manning Hall, on the campus green.

In the meantime, Preucel also hopes that the move to Providence will allow more collaborations with institutions such as the Providence Children's Museum, Trinity Repertory Company, the Providence Athenaeum and the Providence Public Library.

"We really want to contribute to Providence's cultural life," he said.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: RI's Haffenreffer Museum is moving, and repatriating Native American remains