Bud Fowler, co-founder of Adrian Page Fence Giants, inducted into Baseball Hall of Fame

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Bud Fowler was only a part of the Adrian community for a short time, but the all-Black baseball team he co-founded here was part of his legacy that led to his induction Sunday into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

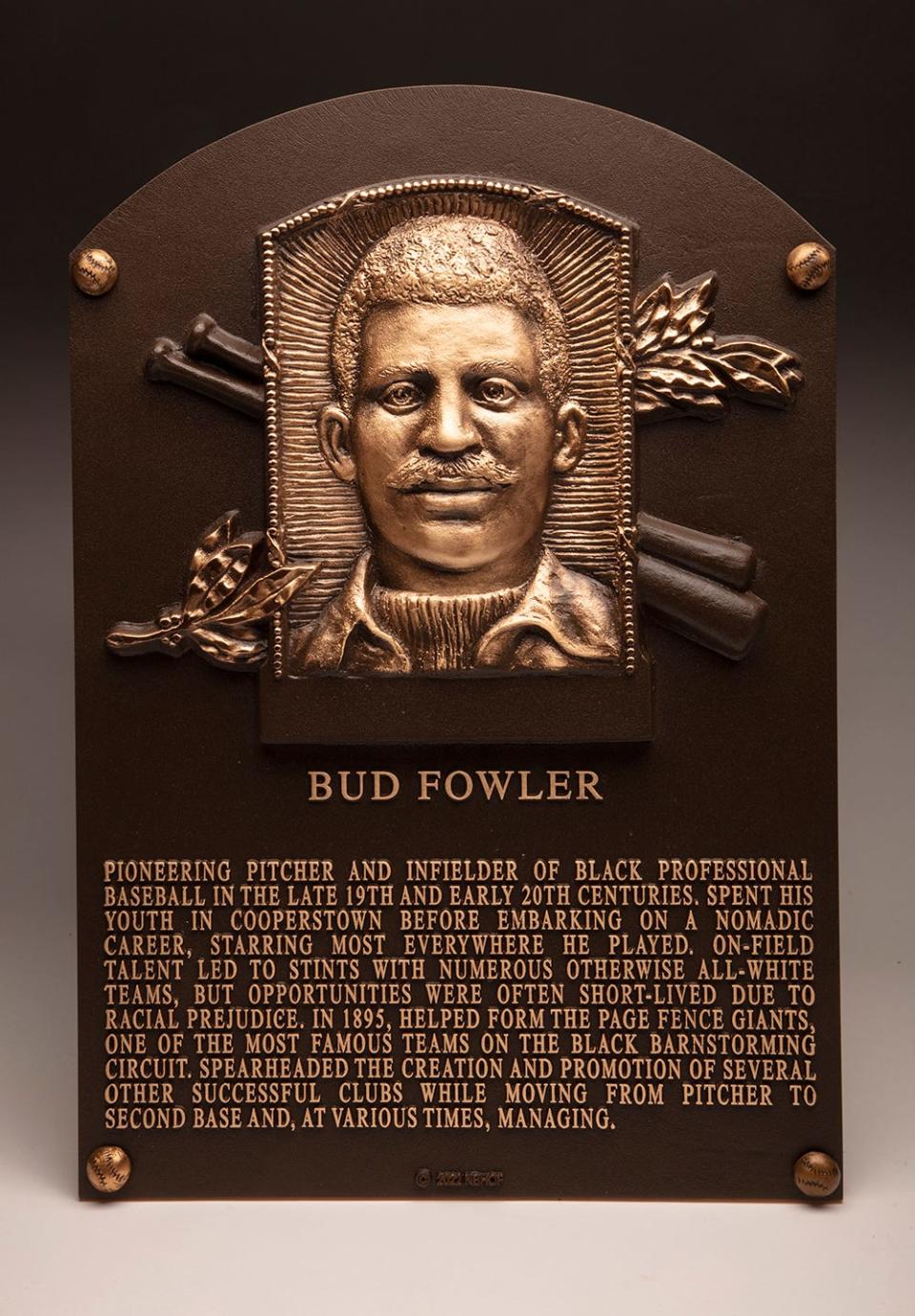

Now, when visitors peruse the Plaque Gallery at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, and find Fowler’s moustachioed visage immortalized in bronze, they will learn the Page Fence Giants were “one of the most famous teams on the Black barnstorming circuit.”

Fowler’s nomadic career in the late 1800s brought him and slugging shortstop Grant “Home Run” Johnson to Adrian in 1894, where they found a welcoming community and a business owner, J. Wallace Page, willing to sponsor an all-Black team. Page’s woven-wire fence company had its plant on Adrian’s east side.

“I think it’s cool for Adrian to be that community that was open and accepting at the time and had the money to support this great team,” said Mitch Lutzke, a recently retired history teacher from Williamston whose book is one of a few projects that shed light on the Giants and Fowler in recent years.

Adrian College communications arts and sciences professor Michael Neal ended up collaborating with Lutzke on a documentary film, "Bud Fowler and the Page Fence Giants.”

“I am extremely happy to see Bud Fowler and his story getting the respect it deserves,” Neal said in an email. “Several baseball historians worked hard to make sure his name was not lost to time over the years and now many others will have the opportunity to learn about his journey for years to come. Fowler grew up as a child and fell in love with baseball in Cooperstown, so it is only fitting that he is now immortalized there.”

“I’ve had people reach out and say the book gave him some momentum or shined a light on him because nobody had written a book on the Page Fence Giants,” Lutzke said in an interview. “…If my book helped to put Bud in a positive light so he ends up in the Baseball Hall of Fame, I was just very, very honored and pleased that my book was probably part of the equation that people examined to get this deserving man the honor he deserved."

Another important contribution to recording Fowler’s importance to baseball was Jeffrey Michael Laing’s 2013 biography, “Bud Fowler: Baseball’s First Black Professional,” Lutzke said.

Lutzke said the Hall of Fame’s Early Years Committee appeared to have taken into account Fowler’s organizational skills as well as his playing record.

Fowler was inducted along with Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso, Tony Oliva, Buck O’Neil and David Ortiz.

Considered the first Black professional baseball player, Fowler grew up in Cooperstown, then moved from town to town across North America, looking for teams whose white players and fans would accept him, but also moving on when he had disputes with management. His travels took him from the northeast to Canada, to the Midwest and out west, recalled Hall of Famer Dave Winfield in his address Sunday about Fowler to the audience at the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, where the induction ceremony takes place.

Fowler’s given name was John Jackson. He became Bud Fowler when he started playing professionally, Winfield said, because he would greet others by saying, “Hey, Bud.”

Fowler was the first Black player to integrate a white professional team, about 70 years before Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947.

Winfield said there is a line that can be followed from Fowler to Andrew “Rube” Foster, who started the Negro Leagues, to Robinson to today’s players.

“It seems simple enough, but knowing the times it was vastly more complicated for him than just signing up to play, no matter what his talents were,” Winfield said. “There was something magical about this game, though, that caught his eye and his imagination that he'd spend the rest of his life playing, managing and imagining what this game of baseball could be.”

During his career, which spanned more than two decades, Fowler played second base, outfield, catcher and pitcher in as many as 50 communities in 22 states and Canada, Winfield said. When he played for the team in Stillwater, Minnesota, he helped break a losing streak and was rewarded with $10 and a new suit.

Fowler’s playing skills were remarked upon in newspaper accounts of games he played in, Winfield said, but he continued to face racism.

“My skin is against me,” Winfield quoted Fowler saying in 1895. “The race prejudice is so strong that my Black skin barred me.”

By 1897, the minor leagues stopped hiring Black players, Winfield said.

Given the racism of the time, Fowler worked on organizing teams. One of those was the Page Fence Giants.

“They traveled in a custom railcar and they went on to become one of the all-time great barnstorming teams,” Winfield said.

That first year, Fowler batted .316 and the team won 118 games to 36 losses, Winfield said.

Lutzke said Fowler only played with the Giants into July before he decided to move on. Home Run Johnson played all four years of the team's existence.

Fowler was a visionary, too, predicting the formation of the Negro Leagues, Winfield said.

“Some 16 years before the creation of the Negro Leagues in 1920, Fowler was quoted in The Cincinnati Enquirer in 1904 as saying, ‘Some of these days a few people with nerve enough to take the chance to form a colored league of about eight cities, they’re going to pull off a barrel of money,’” Winfield said.

None of Fowler’s contemporaries on the diamond got to play in the Negro Leagues, Lutzke said.

Listening to Winfield tell Fowler’s story, it was clear Winfield had done his homework, Lutzke said.

“I’m not sure you could have picked a better person than Dave Winfield to speak about a fellow African-American, great ballplayer,” Lutzke said. “I was very happy it was a ballplayer that was in the Baseball Hall of Fame.”

Fowler never married and had no children, so he had no direct descendants who could have represented him at the ceremony, Lutzke said.

The Page Fence Giants, of all the teams Fowler played for or started, are the team mentioned on Fowler’s plaque stood out to Lutzke.

“I’m, like, wow! The team I wrote my book on is in a plaque,” Lutzke said. “I would probably guess that 10 years ago if you would have talked to people at the Baseball Hall of Fame they wouldn’t have much knowledge of the Page Fence Giants, and now it’s on a Hall of Fame plaque.”

Winfield asked fans to remember Fowler “as a skilled athlete who endured obstacles that are hard to imagine today, as an early force in integrating the game and as a visionary who attempted to create a league of their own when the roadblocks of the time were present, yet he still persisted.”

Fowler is also the first player from Cooperstown to be inducted into the Hall of Fame. The town has recognized his importance by naming the drive that leads to Doubleday Field for him.

Lutzke said he hopes that Fowler’s election to the Hall of Fame will lead to the consideration of other early Black players, including Home Run Johnson, who was on the ballot with Fowler.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Telegram: Co-founder of Adrian Page Fence Giants inducted in Baseball Hall of Fame