How Buffalo’s catastrophic storm response failed a woman in life, then in death

Anndel Taylor believed. She waited.

Then, alone in her car, she died.

It was two days before Christmas, still the early hours of a blizzard worse than any the city of Buffalo had seen in generations.

The snow piling around her tires that afternoon could still be measured in inches, but bracing 70-mph gusts turned ice into daggers.

Howling wind, so loud it maddened even those bunkered in their homes, peeled snow from the pavement and lanced it toward her windshield.

Her little 2004 Nissan Altima could go no farther. She faced a fateful decision: hope for rescue or strike out into a hostile storm.

She called 911 five times while trapped in her car, among hundreds of stranded Buffalonians who tried. Finally, she got the answer she was looking for.

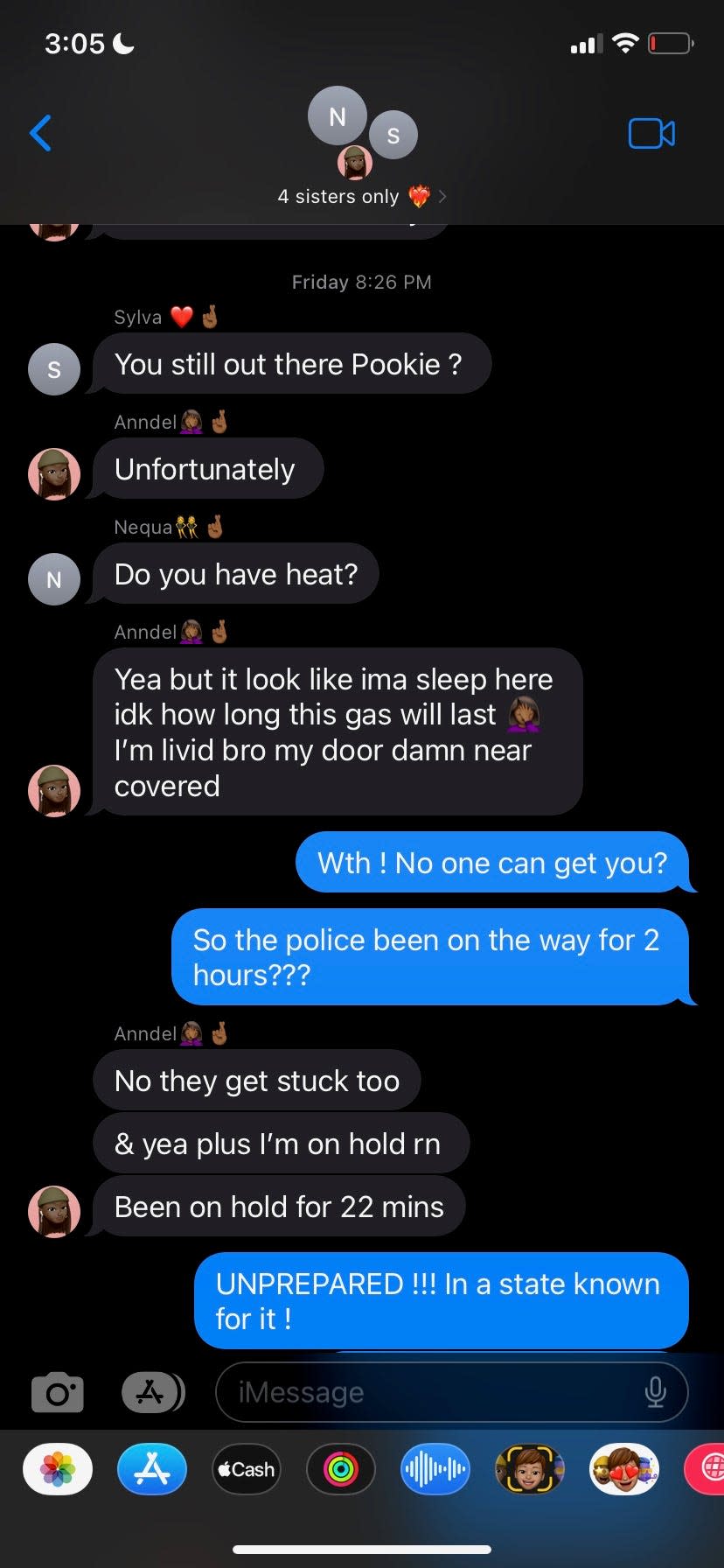

They said they’re sending someone, 22-year-old Anndel Taylor texted her sisters after 9 p.m.

She would wait.

But the blizzard had already overwhelmed Buffalo’s police and fire departments. It would transform the 911 system into an answering machine, and sideline snowplows. The storm would also expose a disastrous lack of coordination among local, state and federal emergency responses, according to an investigation by the USA TODAY Network New York.

Emergency responders gave up altogether on some neighborhoods. Streets stayed snowed in for days, and power outages blinked through the city. It was a series of disparate tragedies and systemic failure so massive it is hard to fully describe. The scope has come into focus only through months of public records requests and thousands of pages of documents.

A team of USA TODAY Network reporters explored how the decisions made by officials before, during and after the blizzard left scores of people, including Anndel, to fend for themselves. The investigation spanned hundreds of pages of government emails, dozens of interviews and reams of emergency dispatch data. It revealed:

Most of the fleet of hundreds of heavy-duty vehicles deployed by the state and National Guard failed to aid Buffalo during the early blizzard response.

The lack of federal involvement stretched into the third day, when a White House adviser watching news reports of the disaster contacted a local official. The resulting federal aid mobilization missed the all-important initial rescue phase.

A lack of cooperation between Erie County and Buffalo city officials hindered emergency response strategy and coordination, as more than 1,000 calls for help via 911 went unanswered for days.

Drivers trapped on roads in towns, villages and cities surrounding Buffalo were more likely to get an emergency response than Anndel and hundreds of other motorists stranded on Buffalo streets.

Fundamental flaws within the region's emergency communication apparatus limited the effectiveness of heroic rescue attempts.

Put simply, emergency management breakdowns cost lives.

When Anndel Taylor’s car got stuck, she was struggling to make it home from work as a nurse’s assistant to be with her ailing father. She didn’t want to leave him alone during the storm.

Now she was the one alone, left to hope that her car would have enough gas to keep her warm until help arrived.

Anndel was the sort of person who always looked out for others, said her mother, Wanda Brown Steele.

Her daughter was kind, said Brown Steele. Persistent. She always followed through. If someone said they would come, her mother said, Anndel would have believed them.

No one came. Anndel died. And that would not be the final indignity.

Anndel’s car was a mere thousand feet from a Buffalo fire station — a four-minute walk on a nice day. That night, police responded to a motorist who was stranded hundreds of feet west of her on the same street. An hour later, they responded to another, hundreds of feet in the other direction.

The wind chill was below zero. The snow was climbing toward her tailpipe. She did not last the night.

Her body was left in her vehicle for another day and a half as caller after caller begged the city to come. It fell to a stranger to help remove Anndel Taylor from her car and drive her to the hospital.

Many first responders, and even more everyday citizens, helped save the lives of hundreds of people during Buffalo’s lethal storm, in tales told and retold amid the grim aftermath.

But the story of Anndel Taylor, among dozens who died in Buffalo’s most fatal recorded snowstorm, exposes the cruelty of chance — and the magnitude of a disaster that was both natural and all too human.

Dec. 19: Danger on the distant horizon

Four days before the storm — early in the morning of Monday, Dec. 19 — meteorologist Mike Fries knew something big was coming.

At this distance, forecasting tools are not precise. He and other National Weather Service scientists had to rely on experience, things they’d seen before. Patterns in the middle atmosphere. The way the low pressure moved and deepened across the surface of the Great Lakes. An atmospheric flow that seemed to draw the storm system across the length of Lake Erie and then to Buffalo.

In Buffalo, home to average snowfall of 95 inches each year, there are storms and then there are storms.

“We knew that this was probably going to be a snowstorm that would be a career event for everybody working at this office,” said Fries, whose official title is warning coordination meteorologist.

A bomb cyclone, an unstable feedback loop in which pressure rapidly drops over a long time, creating precipitous winds. Lake-effect snow, dumping inches that could turn into feet. A potent and angry cocktail.

Their warnings would matter. How would they tell people that this could be a storm the city hadn’t seen in generations, without going beyond what they knew?

A storm like this, said Fries, “changes the way that you think about your work quite a lot.”

Within hours, they were talking to county and state officials.

“We had conference calls, probably at least every hour for several days,” Fries said. They passed around draft after draft of the first storm warning.

That afternoon, the Weather Service put out the first message. A “powerful storm” was likely on its way. By the next day it had been upgraded to “major,” with strong winds, a flash freeze, zero visibility. “The upcoming storm IS a big deal,” blared the Twitter account.

By Wednesday, in intensifying warnings, Weather Service officials called the storm “once-in-a-generation,” with 70-mile-an-hour winds and subzero wind chills that could cause frostbite to exposed skin in less than 30 minutes.

Local authorities issued their own warnings Thursday. Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz said road travel might be near impossible by Friday — with visibility so bad you couldn’t see past the hood of your car. He warned, jovially, that people should postpone that trip to grandma’s house.

Mayor Byron Brown told Buffalonians to “finish up their last-minute holiday shopping” by Thursday. The city canceled Friday’s garbage pickup and closed a few parks and indoor pools.

Neither the county nor the city banned road travel. Nor did emergency alerts push out to phones, warning of the dangers of driving that day.

And Anndel Taylor had to be at work at 6 a.m.

5 a.m. Dec. 23: East Side Buffalo

When Anndel awoke before dawn on Friday, it could have been any winter morning in Buffalo.

It was cold, drizzly, 30-something degrees outside. No snow had fallen. The bomb-cyclone winds that meteorologist Fries knew were coming since Monday had not yet begun to blow.

Anndel was not the sort of person to miss a shift at work, her mother said.

Despite being the youngest of four sisters, Anndel was the first to save enough money to buy herself a car while growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina. A year and a half ago she drove her car up to Buffalo to be with her ailing father, while putting herself through business school by working at a nursing center called Absolut Care of Aurora Park.

“She kept a job, she paid her bills,” Brown Steele said. She made sure she was there for everyone around her. When one of her sisters was short gas money, Anndel dropped $100 into her account, no questions asked. She always showed up.

Sometime before 5:30 a.m., with the sky still too dark to see clouds on any horizon, she got into her Nissan on a hedge-lined East Side street where every house looked a little bit the same. The same A-frame roof built long ago. The same patch of lawn where children might play. The same broad and welcoming porch.

Anndel started the car and left home for the last time.

***

The day before the storm, the county office was already a hive of activity, public records show.

Many city, county and state officials, including Poloncarz and Brown, declined to be interviewed for this report. Some of those officials have publicly defended their blizzard response management, saying they prepared as best as possible for a once-in-a-generation storm that overwhelmed the emergency response network.

State officials also asserted some state vehicles began aiding Buffalo's emergency response when the blizzard began on Dec. 23. But officials have delayed releasing GPS data that tracked the state vehicles during the storm, shrouding the effort in secrecy.

On Dec. 22, the email accounts for Poloncarz and the county’s emergency management commissioner, Daniel Neaverth, were filled with dozens of messages from leaders across western New York.

Officials shared updates on everything from weather forecasts and warming-center plans to college closures and strategies for communicating during the storm.

The same was not true in the City of Buffalo.

Information didn’t flow evenly between county and city governments, records show.

Only one of those blizzard emails went to a City of Buffalo official’s email account that Thursday. It came from the National Weather Service: a standard update on the blizzard warning sent to Public Works Commissioner Nate Marton.

On Friday, the only Buffalo city official looped in via email was Mayor Brown. He was invited to two blizzard planning calls set for 1 p.m. and 8 p.m. that day — hours after the blizzard was due to start.

In the aftermath of the storm, Poloncarz would slam the city for its lack of planning, calling its failure to clear more snow-covered roads “embarrassing” during a media briefing.

While Poloncarz later apologized to the Buffalo mayor, the episode underscored an open secret within the community of the fellow Democrats’ cold relationship.

Seeds of this lack of cooperation were planted months earlier when Buffalo released its snow-removal plan in October. The 64-page document includes plans for securing state and federal help to clear streets. It makes no reference to the county’s role.

Unlike some other cities, Buffalo also lacked an emergency management commissioner, a role that experts say is key to handling natural disasters. That job instead fell to Buffalo Fire Commissioner William Renaldo, who was on a Florida vacation during the blizzard. He claimed to have overseen the response efforts remotely.

Seven people died because EMS response was delayed by backlogged 911 calls, unplowed streets and stranded vehicles causing blockages, an NYU study of the blizzard reported.

One key problem was the fact county 911 dispatch software could only view 25 calls at once — sometimes duplicative — hampering Buffalo's ability to respond to a tsunami of calls, according to the study.

But it's unclear how many of the dozens of others who died could have been saved through improved cooperation between local, state and federal emergency responders, as well as better coordination of 911 dispatch operations, the USA TODAY Network investigation found.

Dec. 23: Absolut Care of Aurora Park, 20 miles southeast of Buffalo

At 8:39 a.m. on Friday, the Buffalo blizzard began in earnest.

The roads were clear at 6 a.m., when Anndel Taylor arrived at her workplace, a senior care facility in an Erie County suburb. Temperatures hovered above freezing.

Since news broke of the coming blizzard, her union had been busy negotiating with nursing homes around the region to make sure workers wouldn’t lose pay if they stayed home during the storm, nor lose holiday pay on Christmas.

That didn’t affect Anndel’s shift from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. Friday. Not yet, anyway.

“When she went into work early that morning, there was no travel ban,” said Grace Bogdanove, vice president of Anndel’s union, SEIU 1199. Therefore, Anndel was due at her job.

People liked Anndel, Bogdanove said. She was ambitious. Someone with a future. She’d ascended in less than a year from dietary aide to certified nurse’s assistant, all while putting herself through school for business administration.

After the storm hit, Absolut Care asked its staff to stay on, maybe through the weekend. They needed the help. But the nursing home also couldn’t require anyone to remain.

Anndel needed to be with her family back home, she told staff. Her father was diabetic. She helped at home with his care. She wanted to be there for him.

She asked to leave 20 minutes early. By 2 p.m., she had already pointed her car back toward Buffalo.

***

During the eight hours Anndel had been at work, 20 miles southeast in East Aurora, the weather in Buffalo had taken a stark turn, with much of the storm’s momentum going northeast.

Rain flash-froze in mid-air. The snow began to dump, shattering into splinters from the force of the winds.

“The cold front came through and the temperatures sank like a rock. The wind came up. We got gusts in downtown Buffalo of up to 79 miles an hour,” meteorologist Fries said.

By noon, temperatures in Buffalo had dropped into the teens, with a wind chill well below zero. By afternoon, amid shredded ice flakes, visibility was fiction. Falling trees laid ruin to power lines. Nearly 30,000 people would lose power in the coming days, in part due to frozen substations.

Erie County didn’t instate a travel ban until 9 a.m., after the blizzard had begun pummeling commuters with whiteout snow.

In the week to come, Poloncarz defended his decision to delay a travel ban until after the blizzard had started. After all, many drivers got stranded well after the ban took effect.

If he’d instated a travel ban the day before, Poloncarz wrote on Twitter the next month, he wasn’t sure it “would have changed anything.”

4:13 p.m. Dec. 23, 2022: Clinton and Olsen streets, East Side Buffalo

The first moment Anndel’s sisters knew something was wrong arrived in the form of a wobbly 14-second video.

In a group chat with three sisters in North Carolina, Anndel sent careening footage of iced-over windows, blasting wind so constant it sounded like the static from an old television, and snow that looked the same way.

Naw cuz, Anndel said in the video as she cracked her window slightly, with a few more choice words about weather in New York.

Stuck in a (expletive) blizzard, she texted her sisters.

She was a goofy girl, her mother said, always trying to make people laugh. The kind of daughter who’d drag her embarrassed dad onto a carousel at the state fair, even as an adult.

But the situation was serious. Just off the freeway coming home from work, the snow had stopped Anndel’s car cold, on a desolate stretch of Clinton Street in Buffalo’s Kaisertown neighborhood sandwiched between the battered rust of a grease factory and a garishly blue adult video store.

But she couldn’t see them, or anything else: Blinding snow made her world small. Even the grease factory 30 feet from her car window looked like nothing but a faint outline, almost imaginary, in the phone video sent to her sisters.

Behind her was emptiness, the bottom of a freeway.

Anndel’s first call had been to her family in Buffalo, who tried in vain to dig their car out to fetch her, they told local news in the days after the blizzard. As fast as they dug out one tire, the other tires iced into the snow.

That family, including stepmother Lasheena Smith, father Handel Taylor, and brother Michael Taylor, is no longer talking to reporters about Anndel’s death. They declined or did not respond to interview requests.

The snow was up to the tires on Anndel’s car, she texted, her muffler damn near the ground. She was down to a quarter tank of gas, and resorted to turning the engine on and off to conserve fuel while keeping herself warm, getting in and out of the car to shovel away snow.

Her brother had called the fire department, Anndel told her sisters. The Engine 35 firehouse stood a thousand feet up the road. Still, it’s unclear whether she knew it was there. The snow made even the nearby houses impossible to see.

Nor could anyone call the firehouse directly. The listed phone number routed to a general fire department dispatch now overloaded with calls.

Should she leave the warmth of the car? Stay and wait for help? No choice was good.

Anndel wasn’t dressed for a hike, not in horizontal snow and subzero chill that could kill exposed skin in minutes. She wore blue nurse’s scrubs and a pair of hospital Crocs.

In Buffalo on Saturday, Congo native Abdul Sharifu, 26, abandoned his disabled car to walk a mile home in the still-raging blizzard. He never made it to his wife, nor saw the birth of his child. Two other Buffalonians chose instead to wait for help in their cars. They, too, did not survive.

At 6:31 p.m., county records show, Anndel reached 911. Fifteen minutes later, she texted her sisters: They’re sending a police officer, she wrote.

Idk how long thats gonna take.

***

An army of emergency responders fanned out across western New York as snow entombed Anndel Taylor’s vehicle.

Though first responders were still trying to reach stranded motorists like Anndel, emergency medical responses had already been halted by an overwhelmed city.

Scores of firefighters and police drove SUVs and pickups onto flash-frozen roadways. Those without snowplow escorts struggled to navigate blinding blizzard squalls and drifts. Dozens of firetrucks and emergency vehicles got stranded during rescue attempts.

Elite SWAT-team members specially trained in cold-weather rescues needed snowmobiles and ATVs with tank-style tracks to reach some motorists. Terrified men and women clung to their rescuers as they were ferried to shelters.

Despite forbidding conditions and stalled cars that halted many emergency responders in their tracks, many units persevered to reach people. Some arrived more than three hours after being dispatched.

These heroic attempts at medical rescue were halted after 6 p.m., leaving about 150 people with emergency medical needs to fend for themselves.

Of the roughly 300 emergency medical calls fielded in Buffalo that first day, only 90 had a unit arrive, records show. Just 18 of those came after the blizzard began intensifying shortly after 1 p.m.

Buffalo Common Council President Darius Pridgen recounted his story of frantically trying to coordinate rescues of neighbors stuck outside in the blizzard.

Trapped inside his home buried in 6 feet of snow drift, Pridgen broadcasted on Facebook that fateful Friday night. He turned to the social media platform in hopes of finding someone capable of saving an elderly couple stranded on a city roadway.

More than 500 people flooded the broadcast with similar pleas for help. The 911 system had buckled at that point, answering calls with a recorded message to try back later. Feelings of fear and helplessness washed over Buffalonians as they shared stories of their suffering, Pridgen recalled.

One woman in a nearby housing project that lost power typed out a request for help with one hand. She used her other hand to pump the oxygen bag that kept her 3-year-old son alive after his ventilator failed.

8:59 p.m. Dec. 23: Clinton and Olsen streets, East Side Buffalo

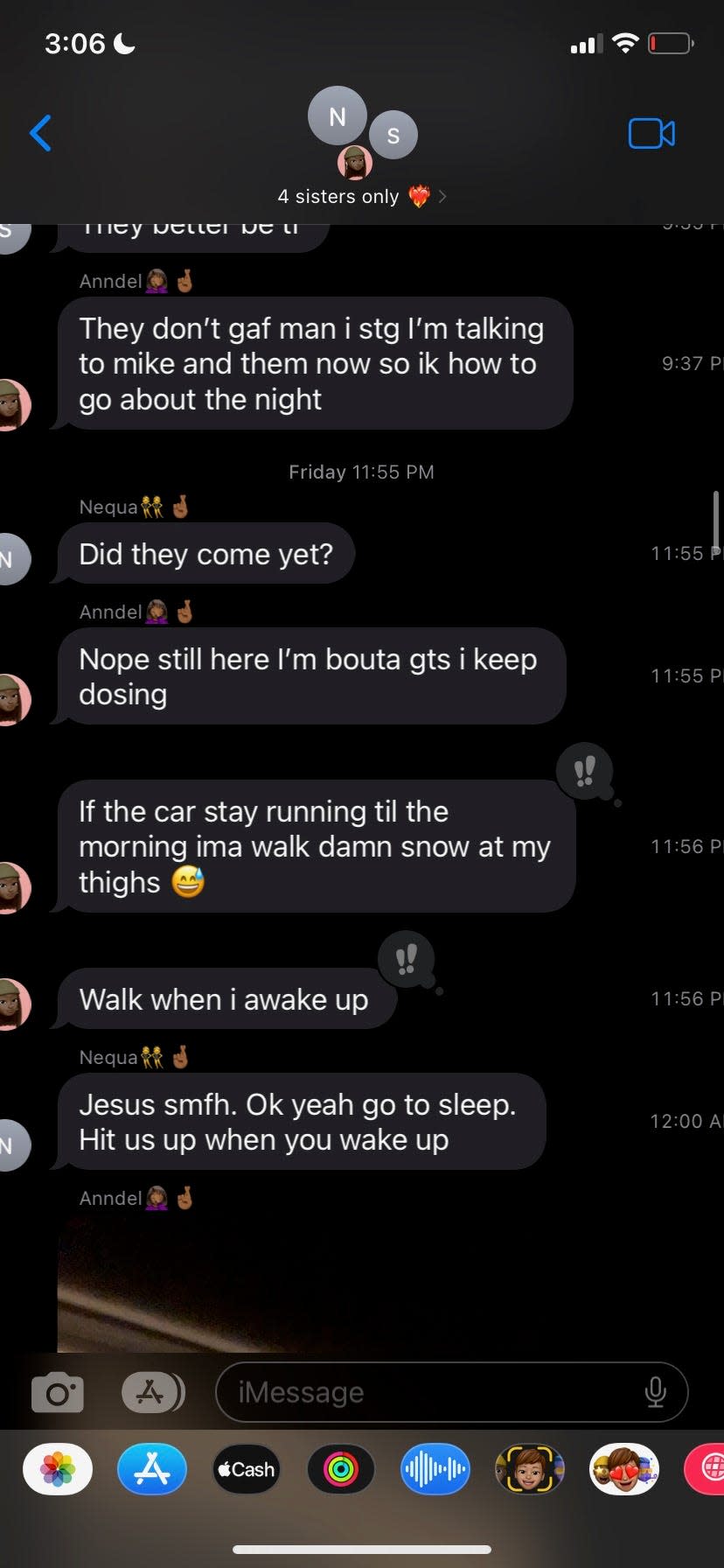

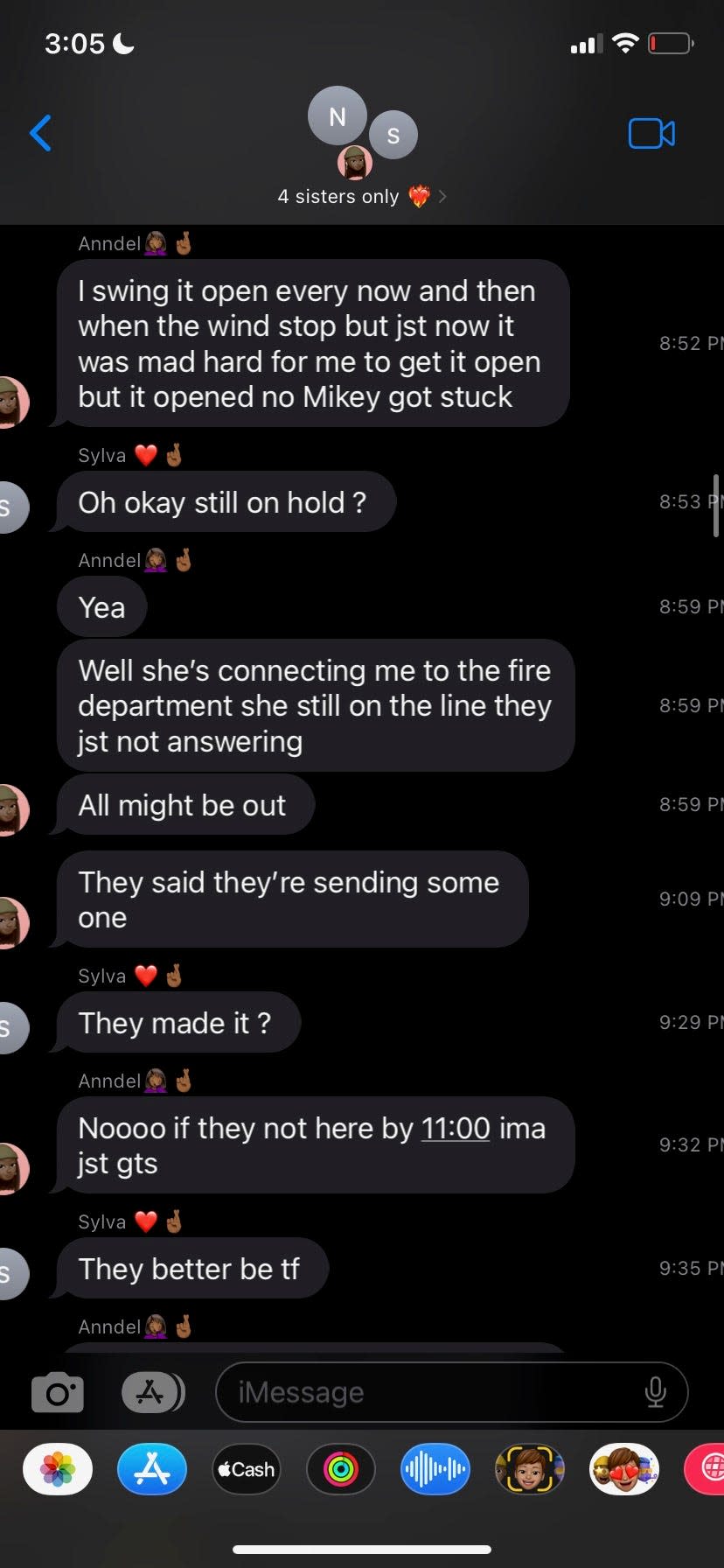

All might be out, Anndel Taylor texted her sisters right before 9 p.m.

The police had gotten stuck earlier on their way to her, she’d texted them. Family in Buffalo couldn’t get anywhere, either.

Her gas was dwindling, and her car door was beginning to fuse shut. When the wind stopped long enough, she kept budging it open, but it kept getting harder and harder to do. The snow was climbing up the car door as fast as she could push it away.

By this time, she had called 911 four more times. Three times she gave up before reaching anyone. It is unknown whether she was placed on hold too long, got disconnected, or reached a message saying all lines were busy.

The fourth time, she stuck it out on hold for more than 22 minutes to finally reach an operator. Now she was on hold again, waiting for the fire department to pick up.

She was losing patience. And hope.

During the afternoon she’d been joking around, said her sister, Tomeshia — and so at first, her family in North Carolina didn’t know how scared and upset she was. Now, Anndel told her sisters, she was livid.

Finally at 9:09 p.m., hope again. For the second time, she told her sisters help would come.

They said they’re sending someone, she wrote.

We know that’s what Anndel believed they told her. Erie County Emergency Management refused requests for recordings or transcripts of the call.

Operators are trained not to tell people that help is en route, according to Marlaine Hoffman, the information services deputy director at Central Police Services.

“The 911 call taker will not tell the caller the police, fire or ambulance 'are on the way,' give a definite time of arrival or otherwise imply immediate assistance,” read the standard operating procedures for the department. “The 911 call taker will advise the caller that ‘help will be there as soon as possible,’ ‘your call has been given to the dispatcher’ or similar phrase.”

What is known, however, is the priority code assigned to Anndel's call.

Emergency calls in Buffalo are given priority numbers according to urgency, with the most violent crimes receiving a code of 1 and 2. Whether during a blizzard or a sunny day, stranded motorists like Anndel are classed among some of the least urgent cases at priority 5, alongside fireworks and illegal poker games. This priority is issued automatically when a 911 operator enters the type of call, Hoffman said.

Buffalo’s emergency system is split between city and county, in an unusual partnership criticized in the June NYU report. The 911 operator is employed by the county, and does not dispatch to city police or fire, Hoffman said. Instead, they enter codes and descriptions.

The operator can adjust this priority manually, Hoffman said. This happened, according to 911 records obtained by USA TODAY Network, for a motorist stranded with children, just as Anndel called the first time. Their priority code was upgraded to 4.

In Anndel’s case, this did not occur. What City of Buffalo dispatchers saw was reduced to two lines.

fem re nissan altima less than 1/4 tank of gas.... MOTORIST STRANDED - CLINTON ST@OLSEN ST. Pri: 5.

***

As Anndel Taylor grew increasingly frustrated and afraid, dozens of emergency responders arrived to at least check on other stranded motorists on nearby streets.

Buffalo authorities received nearly 1,500 calls for help through 911 on Dec. 23. About one in three calls came from drivers of stranded vehicles.

Only 128 calls from the stranded motorists, about one in four, got help from police that first day.

Countless drivers stuck it out inside their vehicles. Hundreds appeared to receive other aid or abandon their vehicles to find shelter, according to the data and firsthand accounts reported during the blizzard.

In some other Erie County communities, responders reached about half of the stranded motorists that first day. Nearly all got a response by the following morning, compared to hundreds of 911 calls that went unanswered for days in Buffalo.

Inside the county’s emergency operations center in Cheektowaga, reports of people dying in Buffalo triggered emotional outbursts and desperate attempts to improve coordination among local, county, state and federal responders, Erie County Sheriff John Garcia recalled.

“We’re here to save people,” he said, “and not to be able to respond and help people, it was absolutely gut wrenching.”

Some of the frustration inside the blizzard headquarters was aimed at state and federal officials, Garcia said. The reason: most of the fleet of heavy-duty emergency response vehicles deployed by the state and National Guard remained sidelined during the early response.

“They had the manpower and the vehicles to get to all these stranded people,” he said. “For two days, the city of Buffalo didn’t have emergency services responding. This is the second-largest city in the state we’re talking about.”

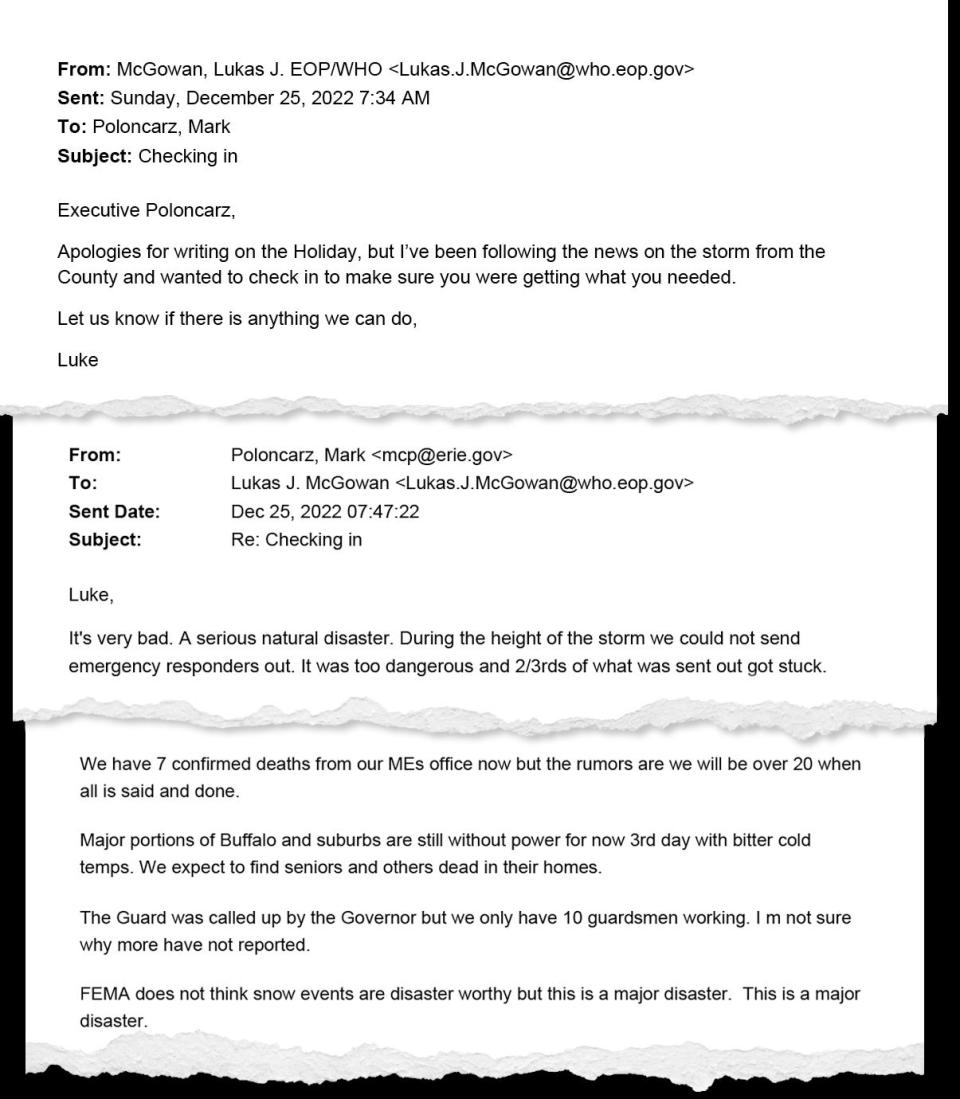

Poloncarz also seemed baffled by the mutual aid failures in his email exchange on Sunday with a White House adviser.

"The (National) Guard was called up by the Governor but we only have 10 guardsmen working. I'm not sure why more have not reported," Poloncarz wrote.

12:09 a.m., Christmas Eve: Clinton and Olsen Streets, East Side Buffalo

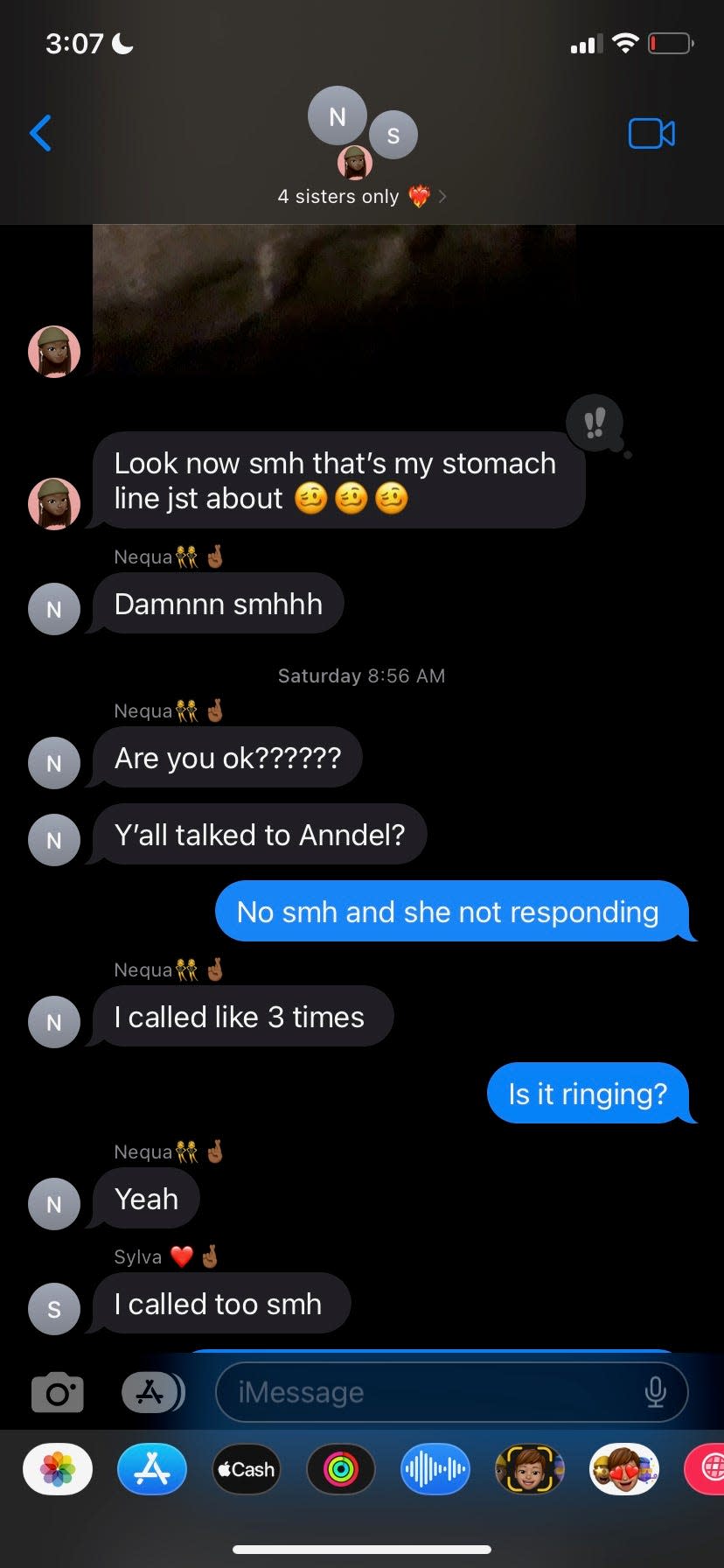

Just after midnight, Anndel Taylor texted her sisters one final video.

There were no words. Just wind, and the sound of Anndel’s labored breathing. She lowered the window to show a world covered in snow. What looked to be a white van with flashing hazard lights could now be seen behind her.

The city didn’t care about her, Anndel had already decided hours before. They don't gaf man, she texted.

She would go to sleep, and then figure it out in the morning.

Snowdrifts piled up against her car door, the video showed. That’s my stomach line, she texted. Her last communication to her family took the form of emojis. It was three winking faces, neither a smile nor a frown, with mouths like Charlie Brown’s or waves in the sea.

Once Anndel drifted off, she never woke.

Freezing to death is painful, and slow. The blood vessels begin to constrict and become brittle. Your fingers hurt. Your nose and ears and toes. Eventually, you hurt everywhere. And then, when the cold in your body reaches freezing, you are spared this pain.

This is not what Anndel’s mother believes happened to her daughter. Her daughter was found stretched out, with her feet up on the dashboard, the way one might nod off in a warm car.

“If she was cold, she would have been snuggled up,” Wanda Brown Steele said.

Months later, Anndel’s mother has still not been able to obtain a death certificate, nor an official cause of death. The city’s vital records office has also not answered queries from this news organization. But Brown Steele chooses to believe her daughter did not die in pain.

Instead, she believes, the falling snow covered her daughter’s tailpipe, 14 inches off the ground, while the car was still running. Carbon monoxide built up in the car as she slept.

Anndel Taylor, her mother believes, died at peace.

***

Just how close did Anndel come to being saved?

The answer can be measured in feet.

One police vehicle responded to a 7 p.m. 911 call for a motorist stuck at Clinton Street and Bailey Avenue. The vehicle arrived at the scene at about 11 p.m., while Anndel was still texting her sisters, and immediately cleared the call as resolved.

The vehicles were about 500 feet apart.

Down Clinton Street in the other direction — a five-minute walk from Taylor’s car — another police unit had arrived at 8:18 p.m. and cleared a stranded motorist who’d called at 8:08 p.m., an hour and a half after Anndel’s first call.

Police also cleared another 10 stranded motorist calls overnight.

Anndel was not among them.

9:13 p.m. Christmas Eve: Clinton and Olsen streets, East Side Buffalo

Officers also did not check on Anndel's car the next day.

Her sisters in North Carolina woke up the following morning and could not reach her. Shawnequa Brown called Anndel three times. Tomeshia Brown tried. Sylvana Moore tried as well.

The family then called 911 on Anndel’s behalf, without success.

Tomeshia Brown went instead to the people of Buffalo. She posted on a Facebook group devoted to helping share community resources with people affected by blizzards. She tracked her sister’s location using the GPS on her phone, posting a picture and a map of her sister’s location.

Last I heard from her was 12 am last night, she wrote. She was still in the same spot stuck. Now she’s not answering her phone and we cannot find her. We found her car and tracked her phone, but no her! PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE.

Within less than three hours, Buffalonians succeeded in finding Anndel Taylor where their city and county did not. A good Samaritan tracked down her car and broke the window to get in.

It was too late.

He told Anndel’s family what he’d found. And at 9:13 p.m., he called emergency dispatch. She wasn’t breathing, he told them.

After her death, operators raised the urgency of Anndel’s call.

She moved from priority 5 to priority 2.

Call Type Changed,” read the 911 report. “DEAD BODY Pri: 2.

Still, no one came. Well into the night, person after person called 911 to report that a woman was deceased in her vehicle.

Another call, reads one report of a 911 call.

Irate caller.

Family called.

Fem upset that fem is deceased, reads another, now after midnight.

The calls continued into Christmas afternoon.

***

Even as the blizzard slowed on Saturday Christmas Eve, emergency response did not recover.

On Saturday, the emergency medical service response system all but broke down. Of 479 calls received, just six response attempts were made. Only four units arrived at their destination. Simply put, 475 people called for help and no one came.

The crisis continued into Christmas Day, as only 12 units successfully made it to destinations, while 277 emergency medical calls went unanswered. By Monday, emergency medical aid began to arrive. The response remained hobbled, with authorities reaching a mere 69 out of 243 medical calls for help.

In the end, more than 1,000 emergency medical calls went unanswered in those early days after the blizzard hit. Hundreds of other 911 calls didn’t see a police response well into the following week.

Andrew Dinsmore, a 47-year-old firefighter from the Rochester area, didn’t arrive in Buffalo until Dec. 26, as part of a team of Henrietta mutual-aid responders.

His first night passed in a downtown Buffalo fire station, as firefighters ate pasta and meatballs while struggling to digest unthinkable news that Anndel died alone within a thousand feet of another firehouse.

“If they knew that she was there, the firemen from that firehouse probably would have trenched over there,” Dinsmore recalled later. “Everybody felt that way — kind of like: Why weren’t we here yesterday?”

Dinsmore, who left his wife and two 9-year-old daughters at home, spent much of his time in Buffalo checking snow-covered vehicles for survivors, or bodies. He breathed a sigh of relief with each empty car, crossing off a list of unanswered 911 calls.

Roads in many poorer neighborhoods remained untouched by snowplows, he said. People mostly dug themselves out, or found their own way to hospitals. When he arrived, many seemed shocked that help ever arrived.

“After a day or two, they probably figured they’re never coming here,” Dinsmore said.

1:48 p.m., Christmas Day: Clinton and Olsen streets, East Side Buffalo

Delicia Williams, known to friends as Lisa, was driving with her 17-year-old son on Christmas afternoon, when her son saw something that made her heart stop.

“That’s the car,” he told his mother. The car everyone’s looking for.

They were on their way to make sure a family friend was OK. First things first, she told her son. But on the way back, they would check in on the young woman her son had seen on Facebook.

When they did, she couldn’t bear to see. Her son instead went to Anndel’s car.

“He came back,” Williams remembered, “and he looked like he saw a ghost.”

She steeled herself. She found Anndel’s body in the car, head rested on her right shoulder and her left knee propped up as though she was sitting back to take a nap.

“I was hysterical” she said. “I was screaming.”

She flagged down a city worker. She called 911. The worker called 911. And Williams found Anndel’s family through social media.

Transit police arrived no more than 15 minutes later, she remembered. Records show them onsite at 2:48 p.m.

Officers told her they’d been getting “a lot of calls like this,” she said. They could not handle the call. Nor would anyone likely be back for Anndel Taylor soon, she remembers being told.

At that moment Williams knew: She could not leave this poor girl alone on the street.

“I'm a mother of six. And I do have a 22-year-old child. And I wouldn’t want nobody leaving my child like a dog out on the street,” she said. “I said, ‘I'm gonna stay here with her.’”

She did. She stayed until Anndel’s brother arrived with a blanket for his sister, only to be overtaken by the full force of grief. Williams did what she could. She called Erie County Medical Center and told them to expect her. They bundled Anndel in a blanket “to keep her warm,” then into Williams’ car. Williams drove her corpse to the hospital.

There, almost two days after Anndel Taylor first called 911, police were on site to respond. Medical staff waited with a gurney.

“I only did what I would want somebody to do for my child,” Williams said, still weeping at the memory months later. “I only did what anybody should have done.”

***

In the months after the blizzard, Common Council President Pridgen, a Democrat, pushed city officials to buy more vehicles capable of navigating blizzard conditions. He urged investing more in a local 311 community aid hotline to act as a 911 backup.

As a pastor, Pridgen also preached to a grieving congregation during two funerals for blizzard victims. Both died while walking during the storm — one woman trying to get food and another man attempting to reach a narcotics anonymous meeting.

The psychological scars from the blizzard, he added, only deepened sorrows from a racist mass shooting and pandemic that devastated the community last year.

“The mental health of our people — especially poor and struggling people — is already at its breaking point,” Pridgen said.

In the face of all the pain, a mobile mental health team served the church, and Pridgen worked blizzard rescue stories into sermons.

“You got to find that silver lining because tragedy will happen,” he said, “but for those who are still here, one of the ways we start to heal is we make changes.”

Sheriff Garcia, a Republican, called on leaders at all levels of government to “figure out how we get better so there never comes a time when you cannot answer emergency calls.”

“We owe it to the people to have the best emergency response,” he said. “And shame on us is if this happens again.”

Today: Looking for answers

Wanda Brown Steele still watches the video of her daughter's funeral. Each time, it feels like she's reliving the day. But it also feels like she's bringing a little piece of her daughter back.

Anndel is still helping people, her mother believes, even in death. The life she led still helps people.

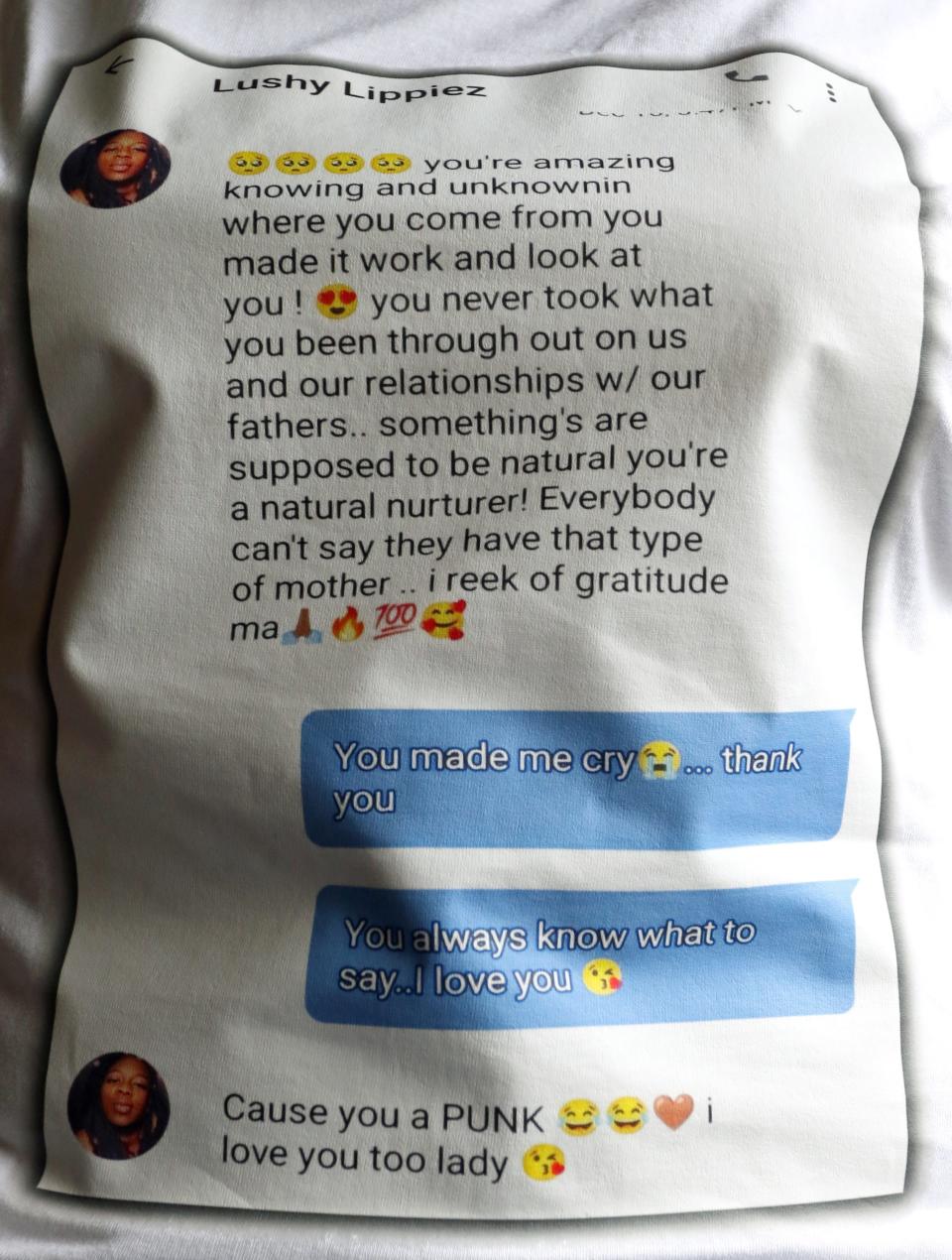

Brown Steele has made herself a T-shirt, depicting the last text messages Anndel ever sent her. A week before she died, she'd reached out to thank her mother for how she was raised.

"I reek of gratitude," she told her mother.

Then, hands praying.

Then fire.

Finally, love.

And then, she made fun of her mother for crying.

Brown Steele still wants answers. She wants accountability for what happened to her daughter — both in life, and then in death.

For not instating a travel ban soon enough to save her daughter from driving to work. For letting Anndel believe that help would come. For not checking on her. For leaving her dead in her car, for more than a day after she died.

She has consulted lawyers, she said. None have taken the case. She doesn’t know where to turn. It doesn’t seem fair, when her daughter did so much for others.

“She left her home to take care of other people,” Brown Steele said, at a Buffalo vigil for Anndel.

"But nobody was there for her.”

Matthew Korfhage and David Robinson are reporters for USA TODAY Network. Matthew can be reached at mkorfhage@gannett.com. David can be reached at drobinson@lohud.com.

This article originally appeared on New York State Team: Buffalo blizzard of 2022: Response failed, investigation reveals