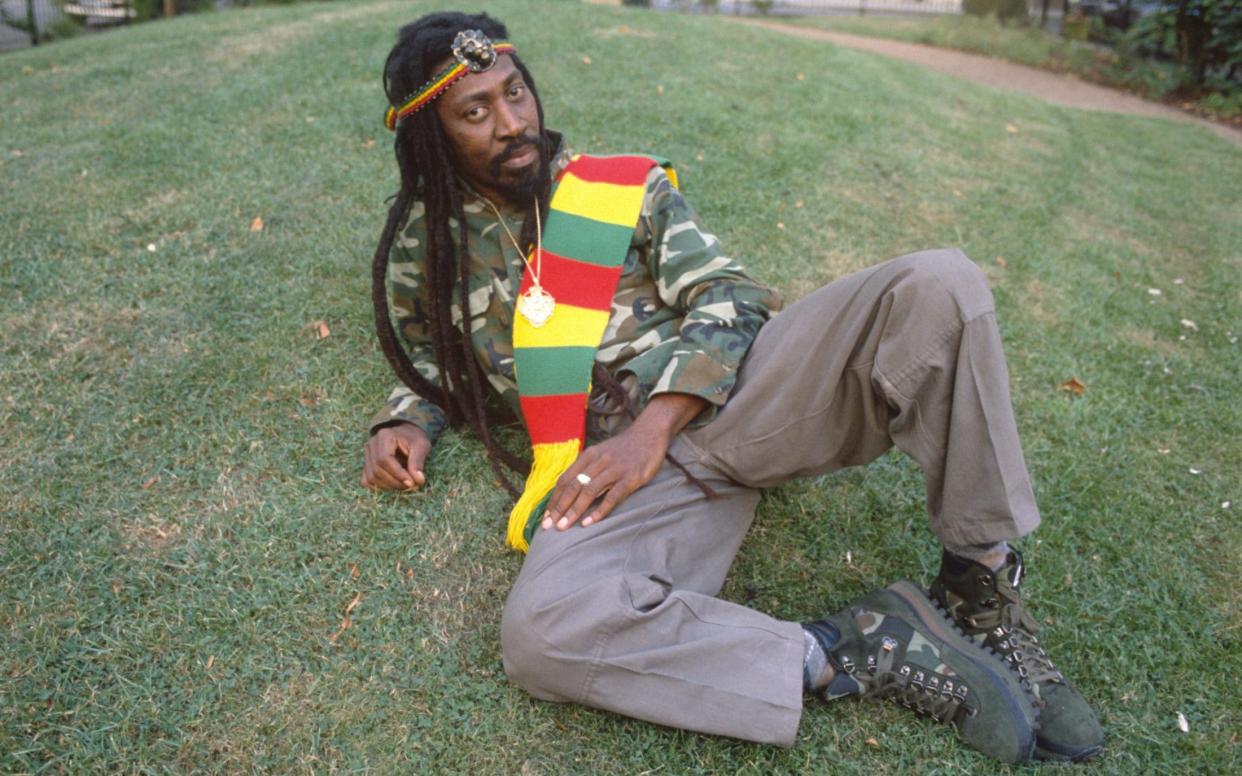

Bunny Wailer, giant of reggae who formed the Wailers with Bob Marley and Peter Tosh – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Bunny Wailer, who has died aged 73, was with Bob Marley a founding member of the Wailers, who revolutionised reggae music; as the only remaining Wailer (Marley died in 1981 and Peter Tosh, the third member, was shot to death in 1987) he was for many years considered the music’s elder statesman.

He was born Neville Livingston, and it was not until much later that he would take the sobriquet of Bunny Wailer, largely as a marketing device for his clear, ringing tenor voice and percussive arranging. His friendship and work with Marley, and later with Tosh, led to them forming the Wailers, an intensely creative and varied trio who gave reggae an immense international reach. Though it is hard to pull Livingston from out of Bob Marley’s shadow he remained a commanding musical figure.

Neville O’Riley Livingston was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on April 10 1947. He first met Marley in the village of Nine Mile, Marley’s birthplace; Bunny was aged eight, Marley two years older.

Bunny was brought up by his father, Thaddeus “Toddy” Livingston, who took him to Nine Mile, where he was preaching. Bunny took with him some experience of music – in Kingston he had been a champion child dancer. At the Revivalist church in Nine Mile where Toddy preached, he banged the drum during hymns.

Although Toddy opened a shop, he was more attracted to the area’s fertile land, perfect for marijuana growing. He financed his assorted businesses through being a “herbsman”, as ganja sellers are termed in Jamaica. After a time Toddy returned to Kingston, taking his son with him, and opened a rum bar.

Bob Marley’s mother, Cedella, had begun working in Kingston, returning to Nine Mile each weekend. One Sunday, she found herself travelling with Toddy Livingston, and they began dating.

Cedella’s son Bob practised singing with Bunny and another boy, Desmond Dacre (later Desmond Dekker); Curtis Mayfield and gospel music were particular influences. The pair soon encountered another youth wanting to try his musical chances – the gangly Peter McIntosh, or Peter Tosh, as he became known.

Toddy Livingston employed Cedella Marley at his bar; she became pregnant and their daughter, Pearl, was born early in 1962, meaning that Marley and Bunny Wailer shared a half-sister. But Cedella Marley decided that her relationship with the womanising Toddy was hopeless and she moved to the United States.

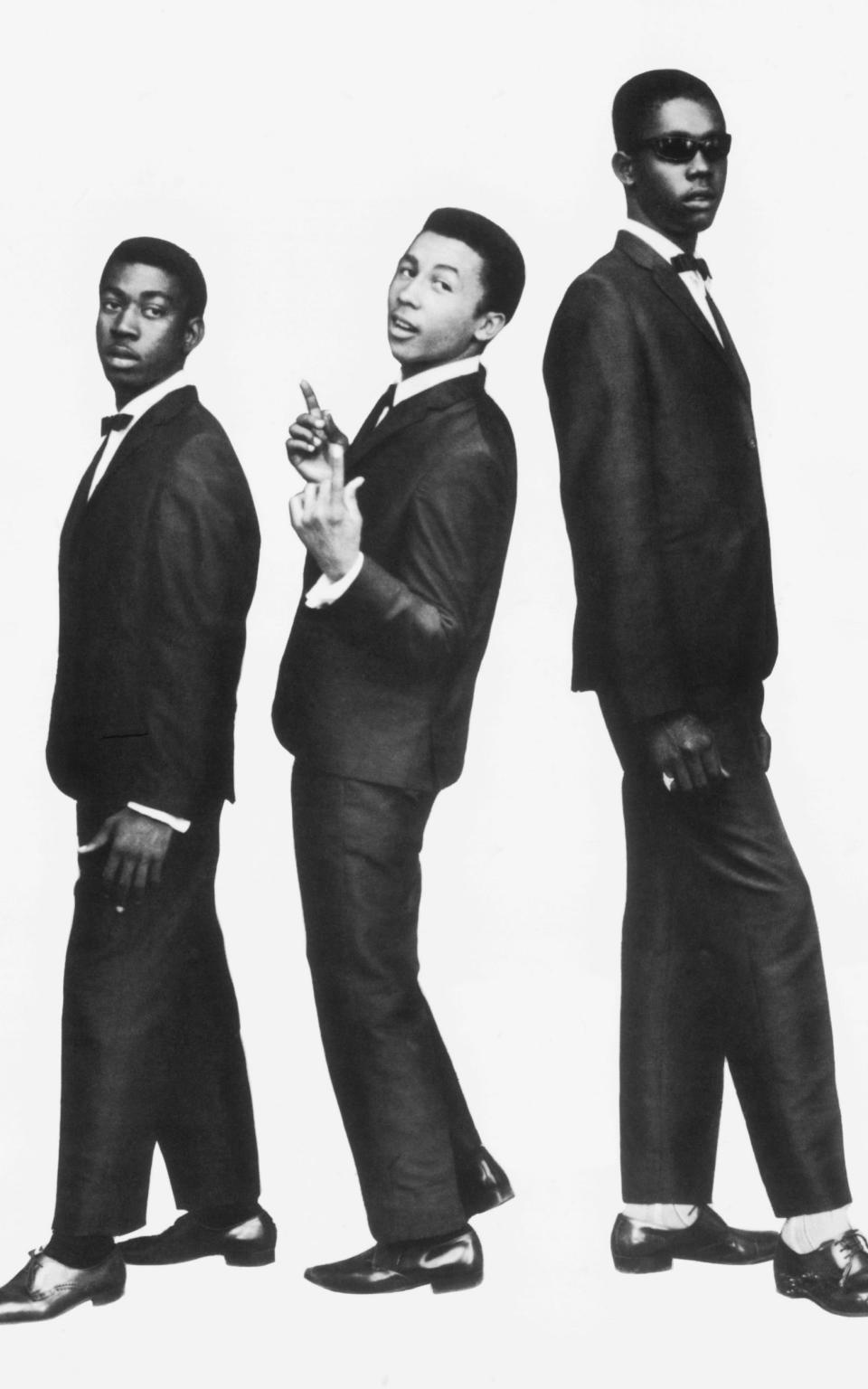

In 1962, Bob Marley recorded Judge Not, his first tune for the producer Leslie Kong. Bunny Livingston had been booked in at the studio the same afternoon, intending to sing his first composition, Pass It On, but had been kept in school after class. A few months later, however, he formed the Wailing Wailers with Marley and Tosh.

They auditioned for the leading producer Coxsone Dodd, and Bunny suggested they play Simmer Down, a song written by Bob Marley a couple of years previously. By November 1964 the song was No 1 in Jamaica.

Though the Wailers were a runaway success, there was a hitch in June 1967 when Livingston was jailed for 18 months for possessing marijuana.

When he was released, he was noted as being more difficult than formerly. In 1970 the Wailers recorded an album for Kong; when Livingston discovered that Kong wanted to call it The Best of the Wailers he was furious. Only at the end of one’s existence could an individual’s work be judged, he insisted; such a decision, he declared, must mean that it was Kong who was near the end of his life.

Laughing at what he considered typical Rasta doublethink, Kong put out the record with his intended title but soon after died of a heart attack – cementing Wailer’s reputation as an “obeahman”, someone who employs Jamaican voodoo-like practices.

Soon after, in a Kingston nightclub, Livingston attacked Lee “Scratch” Perry, who had produced the Wailers’ Soul Rebels and Soul Revolution albums. Perry had sold the records for UK distribution for £18,000 but the Wailers had seen none of the money.

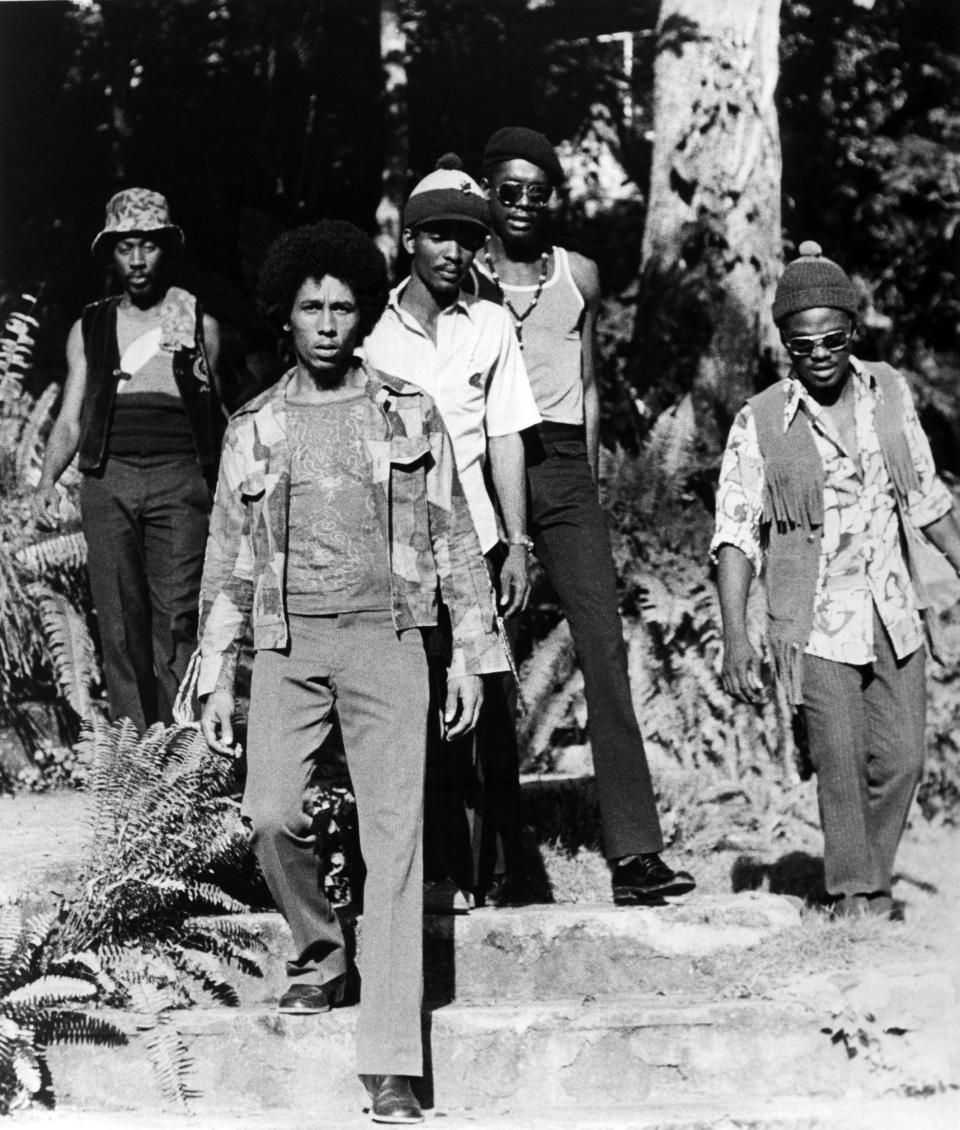

The trio signed to Island Records, whose boss, Chris Blackwell, marketed their albums Catch a Fire and Burnin’ as though they were a rock act. For the second LP a set of US shows had been booked, but Livingston announced that he would not be taking part.

With his girlfriend Jean Watt he moved to live in a bamboo hut among the Rasta beach community at Bull Bay, outside Kingston. Squatting on a piece of land, he built his home himself, adding a touch of luxury with a polished wood floor.

He was the most combative of all the Wailers in terms of black militancy., but when it came to his finances Livingston was on wobbly ground. He had established his own Solomonic label, but it was hardly a money-spinner. Towards the end of the Wailers’ career, he was so broke he was going to sea to catch fish.

As a settlement from Island Records, Livingston and Tosh were each offered $45,000; Livingston insisted on cash. With the banknotes stashed, he drove around Jamaica searching for land to buy. Finally, he discovered a plot in the hilly St Thomas countryside, 60 miles from Kingston, where he built a house.

Livingston seemed to have vanished into this hilltop eyrie, but in the summer of 1976 he released his first solo LP, Blackheart Man, which brimmed with vitality, on Island: he had been saving up songs for some time. He was sensibly remarketed as “Bunny Wailer”, but refused to play dates to push his record. Despite that, his Protest album, released the next year, proved equally strong.

For the 1980 disc Bunny Wailer Sings the Wailers he reworked many of the band’s songs with the backing of the leading Jamaican rhythm section, Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. He experimented with disco on his 1982 album Hook Line & Sinker, and during the 1990s he won three Grammy Best Reggae Album awards, for Time Will Tell: A Tribute to Bob Marley, Crucial! Roots Classics and Hall of Fame: A Tribute to Bob Marley’s 50th Anniversary.

In 1987 he had resumed playing live shows, to large audiences in Europe and the United States, and continued to perform for much of the rest of his career.

But the Wailers dominated. When Kevin Macdonald released his acclaimed Marley! documentary in 2012, Wailer’s voice was conspicuous (he had demanded $1 million to be interviewed, and though he did not get quite that, he was reported to have been paid a substantial sum). His appearance in the film cemented his position as the elder statesman of reggae – though still linked irrevocably to Bob Marley, his schoolboy friend.

In 2017 Bunny Wailer, who suffered two strokes in later life, was awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit. He was married to Jean Watt, known as Sister Jean, who was suffering from dementia; she went missing in 2020 and remained so by the time of his death. He is believed to have had 12 daughters and a son.

Bunny Wailer, born 10 April 1947, died March 2 2021