Burlesque, body-slams and bright masks: How Lucha VaVoom became an L.A. institution

Watching the mesmerizing, in-ring action at a Lucha VaVoom show is a veritable experience. But the wrestling itself is only one flavor of performance on display. From its very first show at the Mayan theater in 2002, the Los Angeles institution has fused lucha libre with burlesque — two forms that require intense athletic discipline and often go under-recognized as legitimate art — and over the last 20-plus years has grown to include stand-up comedy, visual art, low-riders, and a host of other artists under the same psychedelic circus tent.

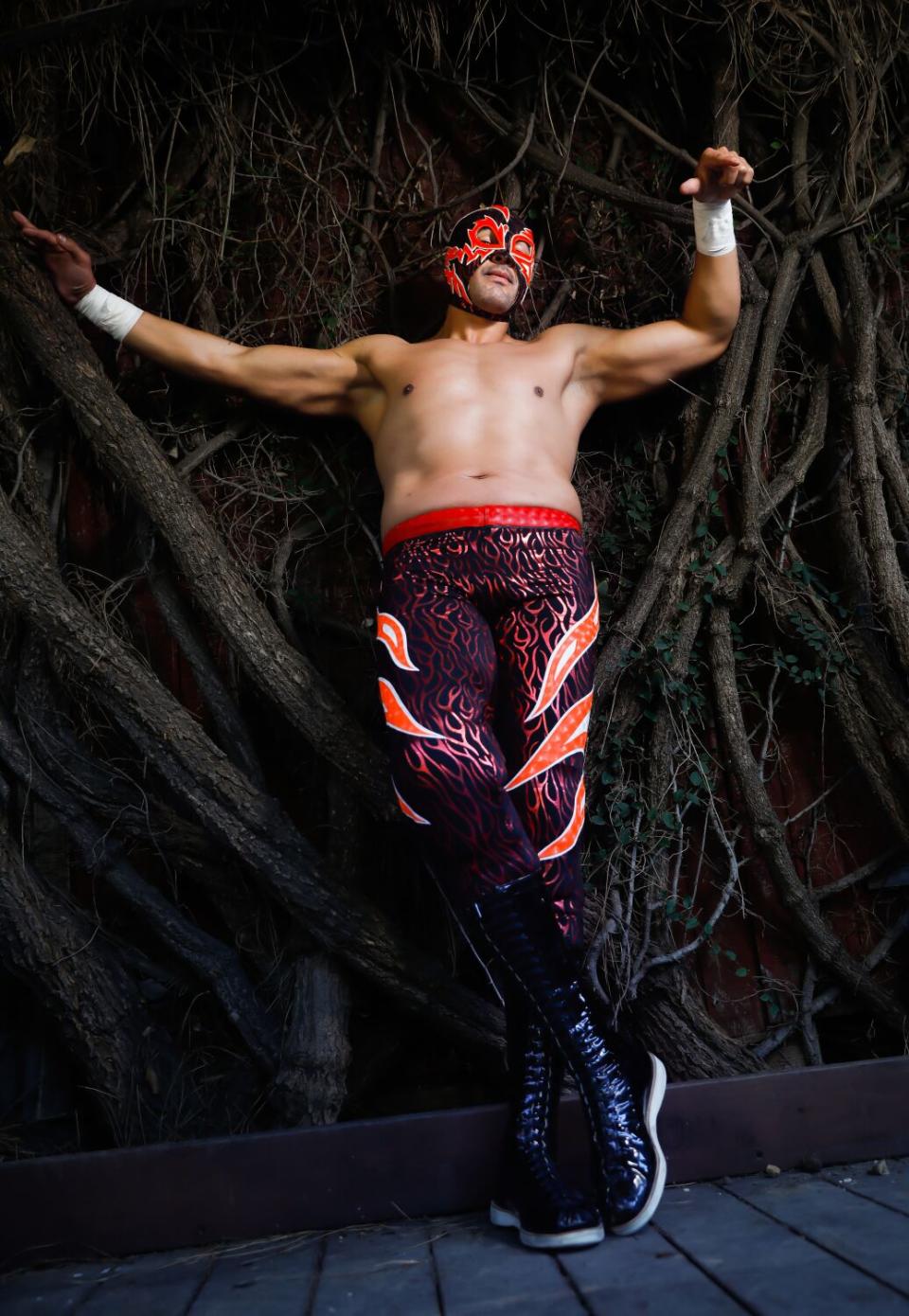

The lineup for LVV’s recent Halloween blow-out, "Bienvenido a la Twilight Zone," featured a motley vaudeville troupe. Alongside dancers and burlesque artists were wrestlers who, true to the event’s name, were conjured from another universe: colorful divas and gifted athletes, of course, but also postapocalyptic cyborg bruisers and human-size chickens. And on Wednesday and Thursday nights, Lucha VaVoom's Valentine's Day spectacular, "Pasión en Fuego," promises to "deliver incendiary burlesque goddesses, twisty contortionists, and death-defying aerialists" in addition to a cadre of luchadores, including Magno and former Lucha VaVoom champion Dama Fina, flexing and strutting their stuff in front of audiences.

Co-founder Liz Fairbairn came to wrestling largely by coincidence, but her background in costume design and stage performance — specifically as the longtime manager of the gleefully camp shock rock outfit Gwar — made the self-described punk rocker uniquely suited to a second life as a lucha promoter.

“I do special effects costuming as well, and I was working on location in Mexico, babysitting some baboon costumes,” she recalls with a laugh. “Luchadores frequently moonlight as stuntmen, and I actually started a relationship with one of them. I wasn’t really familiar with the local wrestling scene at all, but I became fascinated and I started going to shows in Baja and Tijuana with him, and then convincing my, like, quasi-hipster gringo friends from Silver Lake to go down there with us. Eventually, it became easier to just start bringing the wrestlers up here.” Lucha VaVoom began to run recurring shows around specific holidays, including Halloween and Valentine's Day.

Magno, a lifelong luchador from El Paso, was an early performer for Lucha VaVoom and has since become a staple. “I started wrestling when I was 15 or 16, and when I did my first Lucha VaVoom show, I technically wasn’t old enough to get into the Mayan theater,” he says. Because of that 21+ policy, Lucha VaVoom cheerfully embraces camp and raunch and cultivates a crowd that’s both more adult and more varied than your average wrestling show.

“Adults expect a lot more, so you have to hit harder and the matches are even more powerful and explosive,” Magno explains. “I always say doing one Lucha VaVoom match is like doing three matches on another show. But when you step in the ring, you keep on going because you feel the people and want to do the greatest job for them. It’s a one-of-a-kind spectacle because you don’t just get an audience from the wrestlers, you get an audience from the burlesque dancers and other performers. So many people have never seen lucha libre live, but they enjoy it and they start following it.”

For years, lucha libre was stigmatized in the United States. Because the American style so often emphasizes hulking muscles and powerful body-slams, the aerodynamics and acrobatics of lucha were derided as unbelievable and unrealistic — xenophobia and racism certainly didn’t help elevate the Mexican-born art form, either. But in the 20 years Lucha VaVoom has been running shows, lucha libre has developed a huge, ever-growing fan base within the U.S. Many wrestling fans — and wrestlers themselves — grew up idolizing luchadores on American television.

In the late 1990s, companies like WCW and ECW introduced a worldwide audience to the awe-inspiring athletic ability of luchadores like Juventud Guerrera, Psicosis and Super Crazy — and especially San Diego native Rey Mysterio Jr. With entrances and iconic masks inspired by cartoon characters like Spider-Man and the Silver Surfer, Mysterio framed the wrestler as a literal superhero: He became a Peter Parker-like underdog to fans around the world, presenting lucha libre as something much more imaginative and dazzling than its American cousin.

Now some of the most beloved wrestlers worldwide are luchadores, like former AEW tag team champions the Lucha Brothers, Rey Fénix and Pentagón Jr., who recently opened the lucha libre museum Republic of Lucha in Pasadena. Luchadores like Bandido, Laredo Kid and Black Taurus regularly appear on American television wrestling shows like "AEW Dynamite" and "IMPACT!," and Mysterio is still at it over in WWE.

It isn’t just the masks that made the wrestlers. As Magno, explains, it’s that sense of awe that makes lucha libre so appealing to both hardcore wrestling fans and unfamiliar eyes. “What really draws people to lucha is seeing someone do something unexpected, like jumping off the top rope and doing a flip and twisting in the middle of the air and then landing on your feet.”

When Lucha VaVoom began 20 years ago, the indie wrestling scene in Los Angeles was largely separate from the lucha libre scene, a more family-friendly environment almost exclusively in Spanish. Sacramento native and Lucha VaVoom regular Jack Cartwheel, whose jaw-dropping gymnastics have earned him instant love from fans in both the United States and Mexico, has experienced the growing exchange between pro wrestling and lucha libre firsthand. “Now you have a lot of high-flying American wrestlers at lucha shows, and you’ll find a lot of luchadores at American wrestling shows.”

Magno agrees. “American wrestling is evolving," he notes. "It’s not the usual style of punching and kicking, it’s a combination of power moves and flying around the ring.”

But as any wrestler who's worked internationally can attest, no two audiences are the same, and you have to quite literally be on your toes to adapt to the energy and response of the crowd. “American wrestling fans are looking for certain things about your style and psychology and character work,” Cartwheel says. “I feel like lucha crowds just want to come and have a really fun time and support the wrestlers. It’s a much more giving audience.”

For so many wrestlers, lucha libre and Lucha VaVoom specifically offer a laboratory for experimentation and a sense of creative freedom that’s liberating compared to the frequent self-seriousness of American pro wrestling. “In lucha libre, you regularly find people spanking each other or falling on their nuts on the rope, where sometimes American wrestlers are too prideful for things like that,” says Cartwheel. “At the end of the day, you’re doing a pretty silly thing to begin with, so it’s fun that Lucha VaVoom is able to embrace the silliness.”

Taya Valkyrie, one of the most decorated champions in women’s wrestling today, has become a face of Lucha VaVoom — at the Valentine’s shows, she’ll square off in a tag match against her husband, former WWE superstar John Morrison. “Lucha has influenced so much of the style happening in the States,” she says. “You even watch TV shows and Marvel movies and they’re doing lucha moves and you’re like, ‘Oh, my God, did they just do a Canadian destroyer’?”

Before she cut her teeth working for AAA, one of the two largest lucha libre promotions in Mexico, Taya Valkyrie trained as a ballerina in her native Canada, and she continues to bring the mindset of a dancer both to her hard-hitting physicality in the ring and her flamboyant costumes. “I’ve always taken the road less traveled when it comes to fashion, so I’m influenced by a lot of artists and pop culture icons outside of pro wrestling,” she says. “I’ll look to the Met Gala for inspiration, or iconic looks from people like Lady Gaga, Gwen Stefani, Rihanna, Cher, even Elton John, and how they present themselves onstage. I want to create a visual moment for our fans because wrestling is about creating emotions and telling stories, so you have to have a visual representation to complete that experience.”

As a Canadian outsider who spent years in Mexico and now calls Los Angeles home, Valkyrie took to lucha libre because of the creative versatility and expressive potential it offered her as a multitalented performer. But for her, lucha libre is as much about the people watching as herself, a performance determined more by the spirit and emotion of the crowd more than any single style or set of moves.

“Lucha libre is much more theatrical and over the top than professional wrestling, but people try to put lucha libre in a box,” she explains. “They think it’s just wearing a mask and doing a bunch of flips, but it’s not. It’s the way that the fans react. It’s the way that lucha libre is part of Mexican culture. So people have such a respect and passion and love for it. The second you walk through the curtain at a lucha libre show, everything means something.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.