Lawmakers don't have power to use preemption to stop local gun laws the way they think | Expert

Two recent articles in the Dispatch address how the gun lobby has relied on “preemption” to prevent local governments in Ohio and throughout the nation from enacting reasonable gun safety legislation.

In one of these articles, I am quoted extensively (and accurately) as explaining why “preemption“ in Ohio is a myth. This column expands upon my comments.

The Ohio General Assembly appears to believe that it has the power to “preempt” (or bar) local legislation, but the Ohio Constitution neither expressly nor impliedly embraces “preemption” as a general limitation on city power.

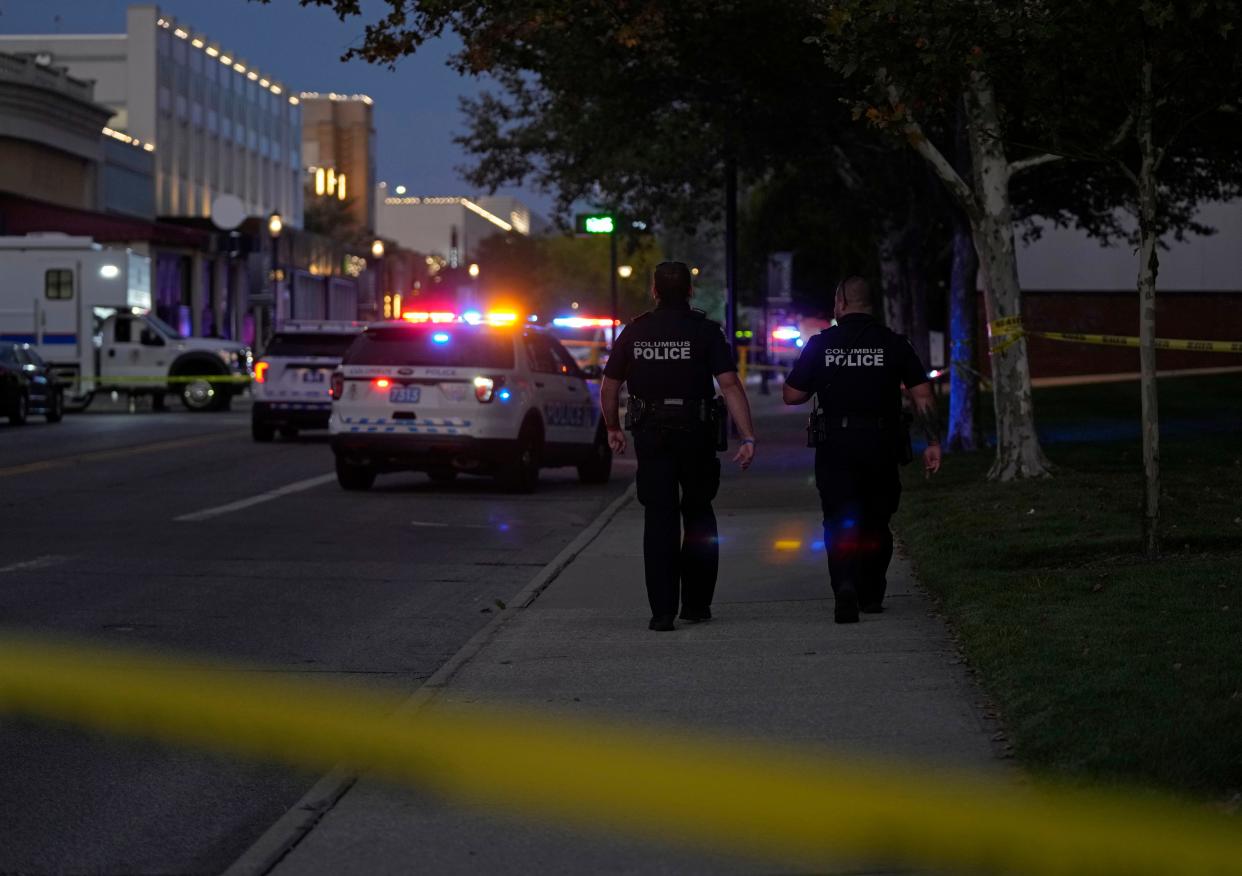

More: Columbus, other cities battling state legislatures in efforts to control gun violence

In approaching Ohio cities as if home rule is an unnecessary relic of the past, the general assembly has ignored why home rule was one of the highest priorities of the Delegates to the 1912 Ohio Constitutional Convention.

Supported by such luminaries as Washington Gladden, the pastor of Columbus’s First Congregationalist Church, the Home Rule Amendment rescued Ohio’s cities from the special interests, particularly the utilities, that largely and often corruptly controlled the General Assembly.

The amendment gave cities “authority to exercise all powers of local self-government” and rejected Dillon’s Rule, the 19th century doctrine under which cities could not legislate without prior approval of the general assembly.

The delegates, however, recognized that city policies would sometimes conflict with legitimate state policies. They resolved this dilemma by proposing language that gave cities authority to adopt “local police, sanitary and other similar regulations, as are not in conflict with general laws.”

More: Ohioans overwhelmingly support gun safety measures, but lawmakers not likely to act

More: Ohio has long history with strict gun regulations predating Civil War

In the debates, the delegates rejected a proposed policy under which the general assembly would have been able to wall-off issues on which cities would be barred from legislating.

Instead, the delegates embraced a conflict approach under which, in the words of Franklin County Delegate Prof. George Knight, only legislation “that in fact and in form touched the subject that affected the state universally” could trump conflicting city policies.

For most of the 20th century, Ohio followed the conflict approach under which the courts interpreted “general laws” to require the existence of a comprehensive system of statewide regulation to reject local legislation; but in recent decades the general assembly began to bar city legislation despite the absence of comprehensive state regulation.

This trickle turned into a flood as the general assembly began to violate not only the letter but also the spirit of the Home Rule Amendment.

Steven H. Steinglass: Past Ohio lawmakers would turn in graves about proposed constitution changes

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the state’s repeated efforts to prevent reasonable gun safety legislation.

For example, state law now broadly provides that cities are barred from adopting legislation that interferes with the right to “own, possess, purchase, acquire, transport, store, carry, sell, transfer, manufacture, or keep any firearm, part of a firearm, its components, and its ammunition, and any knife.”

To support this approach, the general assembly and the attorney general have suggested that the state has a comprehensive “Firearms-Uniformity Law.”

But uniformity is just another name for “preemption.”

When an earlier version of the firearms “preemption” law was enacted in 2006, the state had a wide array of legislation regulating firearms, and the Ohio Supreme Court in 2010 found the state program to be sufficiently comprehensive to uphold the legislation.

Since that decision, however, the Ohio General Assembly, intimidated by the gun lobby, has been on a mission to dismantle state firearms regulation. In so doing, it has gone a long way to deprive state law of whatever comprehensiveness it once might have had.

This deregulation of firearms has been characterized most notably by the removal of state limitations on the capacity of magazines and on the carrying of concealed weapons. And the General Assembly has watered-down the minimal state regulations relating to the safe storage of firearms.

The irony is that to satisfy the demands of the gun lobby, the general assembly has undercut the comprehensiveness of state firearms regulations, and it has thus strengthened the case for cities to be able to adopt reasonable gun safety legislation.

Steven H. Steinglass is dean emeritus and professor emeritus at the Cleveland State University College of Law.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Does the Ohio General Assembly have the right to stop city gun laws?