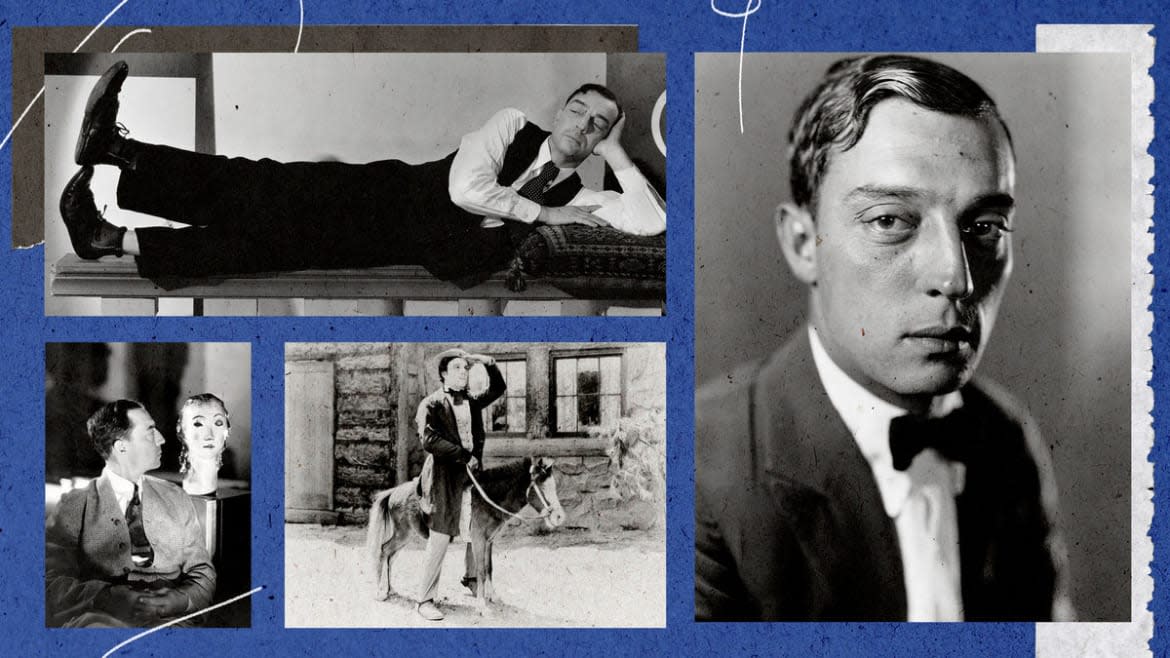

Buster Keaton Has Been Kicking Charlie Chaplin’s Ass for More Than a Century

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Few skills in life—and make no mistake, it is a skill—are more vital to maintaining one’s humanity than finding a way to laugh. Essential, too, is the individual who makes us laugh. This is one reason why no one has ever been more necessary in the history of cinema than Buster Keaton, and why we’d be wise, even today, to spend time with his perpetually modern self.

Years ago, home in the summers from college, I embarked on a Buster Keaton odyssey. On Fridays, I’d take advantage of the rent 10-for-1 deal, departing the store with a stack of Buster Keaton VHS tapes balanced against my chest. Come Monday, I would have been thoroughly wowed in a manner I’ve only been a handful of times in my life. By the Beatles, Beethoven, the short stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thoreau’s journals, and mid-period Billie Holiday.

Charlie Chaplin was then still celebrated as the genius visionary of the early age of American cinema, his Little Tramp character touted as the most iconic creation of the cinematic medium. Chaplin, I thought? Nah. Come on. Anyone could see that Keaton wasn’t just the man, he was the force of life.

There’s been a course-correction when it comes to Keaton v. Chaplin, with the former having been at last critically elevated to his rightful perch. Thus we have a book like Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life, by James Curtis, which attempts to do for the magisterial Stone Face what Simon Callow has been doing biographically for Orson Welles, though in a single volume rather than Callow’s four.

Are the Marx Brothers Still Funny?

Curtis’s three-word subtitle speaks volumes and is voluminously respectful: Keaton is an artist. Not a clown, not “just a comedian,” a yucks purveyor. He’s a filmmaker like Jean Vigo was a filmmaker, and John Ford, and Howard Hawks; only, Keaton may be better than all of them.

Comedies get the shaft when it comes to cinematic prestige. But a work of comedic movie artistry is akin to that person you have with you in the car on the long trip to a funeral. It’s going to be a tough day, it’s a pain to get there, and having this person along for the ride—and the ride back, crucially—helps you get through it, and maybe helps you learn a thing or two about life and death and purpose and truth. When you get to the church, though, your buddy isn’t allowed inside. Not dapper and dour enough. Too real. Your buddy could well be a Buster Keaton comedy.

Curtis treats Keaton’s films the way a Hawthorne scholar would regard the stories: art for the centuries that’s not going anywhere. They’re discussed as movies we can watch again and again, always gleaning new insight. This is no book-length apologia for comedy, nor is it some jargon-y exercise in mental onanism that one gets so often with the sort of academic writings that endeavor to take Keaton’s comedy seriously.

The sound years were not kind to Keaton, being stripped as he was of the hyper-visual core of his métier. To hear him speak in a movie must have been shocking at the time, Keaton sounding like he’d just gargled a bucket of rocks. In writing about the whole Keaton shebang, Curtis’ text wears thin just as Keaton’s own later material did. Once you get past Keaton’s silent era masterpieces, the book is for completists, which is no knock. But to probe on the silent film years is to explore purely transformative art.

Welles believed there is no finer American picture than Keaton’s The General (1926), a film about the love between an engineer and his train. If you watch it once—and you should, if you haven’t, and get your kids in on the action, too—you’re apt to view it 100 times, because within a Keaton masterpiece, we see ourselves, and are summoned back. It doesn’t do to call his characters Everymen. That sounds folkish, loose, not nuanced and specific. That’s the trick, though—to imbue a character with quirks and specificity, gradations of personness, but such that anyone can instantly identify with the central human. This is the Keatsian art, as well as the Keaton-esque.

Keaton’s characters, as he wrote them, played them, directed them, shepherded them, are on the verge of the tragic, or just plain stuck in the ruts of tragedy itself. These are the ruts of life. We all end up in their weathered grooves. I’ll watch a film noir where someone is shanghaied and it’s off to a tour of misery on a sealer ship, but another character still has some witty line that makes our protagonist laugh. When you’re at the hospital for the death of a relative, there comes a remark that causes you to smile. Humor is not cheap and commonplace. It’s as real as pain, the loss of love, the breaking down of the body; it’s what makes those realities of life manageable.

What we find in Curtis’ discussion of the best Keaton films is the idea that humor isn’t merely a coping agent. It’s a way of being, and if we don’t have some version of that way of being tattooed into our souls, we’re going to have a bloody awful time of just about everything, and we’ll also struggle to process and revel in joy, when it is at hand. Humor, as Buster Keaton understood it, doesn’t just get us through; it hoists us up so that we can see the world better, and we become people who exclaim “Ah hah!” rather than “Uh oh.”

Keaton was a quintessential American artist, something we don’t have anymore, though a surfeit of them—or just one—would serve us well. I don’t mean in the Woke way, the anti-Woke way, the leftist way, the conservative way. All of that constitutes trappings, and trappings don’t last. They get transcended and moved beyond, often with a rapidity that people don’t expect, though it happens repeatedly.

The quintessential American artist is a protean, power artist. They were modernists before modernism and beyond modernism. They are an amalgamation of styles, voices, selves within a prevailing self. There’s Melville, Thoreau, the oratorical Lincoln, Welles, Louis Armstrong. Listen to Armstrong play “West End Blues” and the solo he takes. It’s “against the rules,” and it answers only to this person’s imagination and the possibilities of that imagination. Keaton’s The General is the same. It celebrates a love of a thing—the train itself—which is shocking in this age when so many people go on about de-cluttering, and minimalism, and experiences over things, which becomes this kind of rhetorical cover-up for the reality that people don’t have that much in their lives.

Keaton was an artist focused on the value of interest, and I don’t mean what is happening in the savings account. He’s a portal-eyed lover of the possibilities of human existence, and when one fits that bill, the individual becomes someone who lives truly. A cynic might counter by saying that Thoreau was fastidiously spartan, and Keaton’s pictures are governed by the rigorous discipline of craftsmanship, but Thoreau’s main interest was the whole of the world outside his cabin or bed roll—nature—and nothing is mangier than that, be it the nature of the fox and the owl, or the human and her neighbor.

Meanwhile, when Keaton famously stood in a street and the side of a house toppled from above, with our hero only surviving because he passed through the space where a window would have gone, he was bringing a Joseph Cornell shadow box to life with Gordon Matta-Clark slashing, feral impishness. Keaton is our ultimate cinematic power artist, because even when we gasp—as with the narrow escapes in The General—the chance for a laugh is never far off.

A treat of a balanced study like Curtis’ is that films that never got the glory now get some. For Keaton, this means the shorts. In that truncated medium, he’d abandon natural order for the purpose of teaching us about what orders our world, or what should. Magic abounds, optical illusions that make a hard charge on becoming the status quo. You could even say that if you’re a diehard Keaton person, you gravitate towards the shorts.

Describing the short film Cops (1922), Curtis writes, “As was always the case with Keaton, the simplest concept yielded the best results,” which is true enough for this film in which Keaton is chased by the whole Los Angeles police force, but it’s like the cartoon-on-the-page qualities of Voltaire’s Candide have been brought to visual life.

Curtis has enthusiasm, but his writing is full of clichés and phone-it-in-sentences. Still, there’s no stifling the correctness of judgment that breaks through, stoking enthusiasm.

But Keaton is the artist here. That’s the watchword term for him. “Filmmaker” fits under the umbrella, because we’ve lent that word a pedigree of class, the same as the French theorists of the New Wave once did with auteur. But I want to call Keaton an author of life, because that is what the truest artists are going to be, regardless of their medium.

Buster Keaton was—is—an artist who could make the train jump over the gap from one side of the broken track of human life to the solid ground of the other—ground meant for moving forward. To paraphrase the name of Keaton’s titular ship in The Boat, do you know how damn fine that is? Damn human. And forever.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.