The butterfly effect of Shequila Morrison, one of Milwaukee's hardest working activists

By the time the funeral for Rochell Wallace’s son was over, she was exhausted.

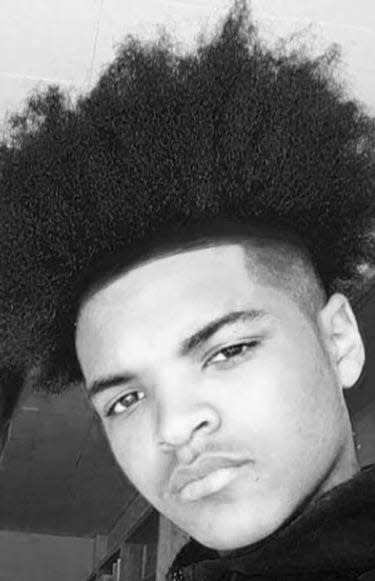

She got ripped off by a man who agreed to make T-shirts, bookmarks and an obituary for her son, Josiah Wallace, 22, who died in a shooting in 2020.

She got into an argument with a staffer at the funeral home during the service. She was tired of being told by others they knew what she was going through and she was “so strong.” When she picked up her son’s ashes, they were handed to her like it was a FedEx package.

Josiah was someone who had a lot of admirers. He was an entertainer on the high school basketball court. He was a ladies’ man – sprinting to help a woman carry something out of a car. He snuck friends into his childhood home if they had nowhere else to sleep. Hundreds attended his funeral.

And his mother still felt that many people she encountered during that time were "ingenuine.”

But after some time passed she received a message from Shequila Morrison, a community activist. Wallace had come to know her somewhat. Morrison showed up at the homicide scene and the vigils that followed. She prayed with Wallace and offered any other help she might need.

In her message to Wallce, Morrison said she wanted to paint her a wooden butterfly in memory of her son. It was delivered soon after – red and bearing the phrases, “Up Top Joe,” “Bro,” “Dad” and “Son.”

“She was very genuine,” Wallace said. “For me, it is a breath of fresh air so that you know there are people like you in this world, people who really care.”

Morrison’s butterfly gifts are a simple gesture. They are store-bought, wooden figurines painted by Morrison and adorned with names of homicide victims and other features. She calls it the "butterfly effect" and it's become a treasured side project for one of Milwaukee’s most dedicated community activists.

She helps women escape domestic violence situations, goes to homicide scenes, comforts family, offers resources and helps navigate the funeral process, like many others do in Milwaukee. But Morrison’s vast local connections, lived experience and affable personality forge a lasting link between grieving family members and the community at large.

It is symbolized by her butterflies.

“I call it the ‘after-the-casket-drop effect’ and what I mean by that is the day after the funeral, we got to get back to real life,” Morrison said. “Some people can’t get back to real life, depending on how close that individual was. I never understood that saying until my dad died. I couldn’t get on with real life. I was stuck."

Finding a flow in community work

Morrison has always been drawn to community work. She has relatives who died by homicide and in car crashes. She has helped search parties find missing community members. When she organized car washes in 2015 after her brother died to pay for his burial, that's when she learned "the community most definitely steps up,” she said.

It’s something she thinks about often when she steps up for others.

Her activism has steadily increased in the last eight years, but it took time for her to find a flow.

In 2018, her father and uncle, who she was both close with, died from health-related issues and the loss threw her off balance for months. At the time, she worked with a grassroots organization that assisted families of homicide victims, but the man heading the group was a “bully” who ruined any sense of fulfillment, she said.

She took some time off, both to grieve and reconsider her mission.

In 2019, she took notice of Vaun Mayes’ social media – one of the city’s most visible community activists and the founder of Community Task Force MKE, or ComForce, another grassroots activism group. Morrison attended a basketball tournament Mayes organized in Moody Park, where she met 20-year-old co-organizer, Quanita “Tay” Jackson, who reminded her of herself. The two spent the day together.

The next day, Jackson was killed in a shooting across the street from the same park. Morrison bonded with Mayes over the loss and has been a member of ComForce ever since.

“This work for us is an escape for the stuff we go through,” Mayes said. “I think that was an outlet for her.”

Nowadays, wherever Mayes goes you can often find Morrison’s always-changing but always-colorful long, braided hair right beside him.

Morrison, 40, has lived in Milwaukee her whole life and has a background in the city’s music and club scenes. When they turn up after homicides, Mayes feels out the situation while it’s Morrison who typically recognizes someone, who can then plug them into whoever knew the victim.

Mayes confesses he is more introverted and does not have the time to build long-term relationships with the people they help. But that is where Morrison excels.

Recently, Mayes said, the two were standing near Sherman Park when a car pulled over. The driver was someone Morrison worked with years ago and wanted to invite her to a memorial for their lost loved one. (When reminded of the story, Morrison laughed and said, “Yeah I got my faves.”)

“Clearly that person held her to (such high esteem) where she recognized her by face, just randomly driving by, and stopped in the middle of traffic to have that conversation with her,” said Mayes.

The butterfly effect

Over the years, Morrison has tried a number of ways to provide comfort to Milwaukeeans in a crisis. In 2015, she started gifting plants, but found that “not everybody’s got a green thumb” and when the plant died, it just made them sadder, she said.

The butterfly sets have taken various forms over the years. Different sizes, shapes, motifs. Some come with picture frames. Some butterflies are accompanied with a painted, wooden arrow. Some have glitter, some have stickers.

They are not strictly reserved for those affected by homicide – although that is the focus – and they are not reserved for families of victims either. For the latter, the butterflies can act as a kind of reassurance.

Dee-Dee Davis joined ComForce more than three years ago. Like Morrison, she’s been active in the community in various ways. That’s how she met Pedro Millan, 19, and Jose “Rico” Stanton, 28.

Davis used to work at Shalom High School, where Millan was preparing to graduate in spring 2020. Previously, he focused on ensuring his young brother stayed in school while he himself struggled and missed class frequently, until Davis took him under her wing.

At the same time, Davis was active in organizing local social justice protests. On the streets, she crossed paths with Stanton, who provided security for marchers and brought them food from sandwich shops.

When Millan acted out in class, he would be sent to Davis’ office, where she put him to work. He would visit her home after school to study. They talked about his plans for the future, which involved perhaps a career in construction. Millan's mother, Sherlene Dunson, credits Davis for helping turn things around.

When Davis marched into the night, it was Stanton who was checking on her. For a year and a half, he would call, text and FaceTime Davis, to see if she needed anything. When she asked why he did this, Stanton said he just cared about everyone marching.

In April 2020, Millan was shot and killed in a dispute that prosecutors admitted they didn’t fully understand. In December 2021, when Stanton was working security for a hotel, he was shot and killed after he intervened with a disruptive guest.

Davis had a unique friendship with both men. She considered them sons, but was not close with their families and did not know them outside of Millan’s schoolwork and Stanton’s activism. It made the grief more complicated.

Both times, Morrison surprised her with a butterfly set. Both times, Davis felt reassured that her relationship with them was acknowledged.

“I was like, ‘Yeah, I lost my kid,’” Davis said. “I thought it was dope. It just never dawned on me that she would think about giving me one.”

The ease of offering support

Morrison admits the creative process behind her butterfly sets is not time-consuming, nor is it difficult.

“The longest part is probably waiting on the paint to dry,” she said.

But the simplicity doesn’t reduce the impact. Her recipients leave the sets on their bookshelves and dressers. They look at them every day.

By now, Morrison estimates she’s given around 800 butterfly sets.

Mayes knows Morrison isn’t the only one who does the kind of work she does. But more people should take cues from her, he said.

“It’s a great thing – especially people who have themselves been a victim – to support people in need,” he said. “We should all be supporting and all have something for giving back.”

Contact Elliot Hughes at elliot.hughes@jrn.com or 414-704-8958. Follow him on Twitter @elliothughes12.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Community activist's art pieces create "butterfly effect"