How to buy a historic lighthouse from the U.S. government

The U.S. government is not going to give you a free lighthouse — unless you are a state or local government or a lighthouse-preservation-oriented nonprofit. But you can buy one. And they aren't as expensive as you might expect.

Since 2002, the U.S. General Services Administration has held an annual auction for historic lighthouses that the U.S. Coast Guard has determined are no longer needed by the federal government. The disposal of historic lighthouses was authorized under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 (NHLPA), and the law's first priority is to give light stations free of charge to public bodies or nonprofits that will maintain them and open them up to the public.

In cases where no such group applies to be gifted a lighthouse or the National Park Services doesn't find a suitable steward, however, the GSA auctions the lighthouse off to adventurous private bidders "who love waterfront living and historical restoration." Four lighthouses are being auctioned off in June 2023, with starting bids as low as $10,000. The previous 70 lighthouses auctioned to the public since 2002 sold for $10,000 to $933,888.

Here's a look at how — and why — you can buy your very own lighthouse.

Why is the U.S. government selling off lighthouses?

Modern navigation technologies, especially GPS, have made lighthouses less important for mariners, and in some cases obsolete. But the shipwreck-preventing beacons to sailors of old still hold a strong pull in the popular imagination.

"People really appreciate the heroic role of the solitary lighthouse keeper," John Kelly at the GSA's office of real property disposition told The Associated Press. "They were really the instruments to provide safe passage into some of these perilous harbors which afforded communities great opportunities for commerce, and they're often located in prominent locations that offer breathtaking views."

Those same old lighthouses, with their breathtaking views, are also often dilapidated and in need of costly repair and upkeep. Selling off unneeded lighthouses as a "seaside or lakeside retreat" to romantics and history buffs "takes a burden off taxpayers for maintaining the properties," the GSA notes.

What historic lighthouses are for sale in 2023?

The four lighthouses up for auction in the GSA's 2023 "Lighthouse Season" are in Ohio, Michigan, and Connecticut.

U.S. General Services Administration

The Penfield Reef Lighthouse (1) outside Fairfield, Connecticut, "contains a 51-foot-tall octagonal lighthouse and a two-story, 1,568-square-feet keepers quarters" that was "built in the Second Empire Style" in 1874 and restored in 2015, the GSA says. It is accessible only by boat.

The Stratford Shoal Lighthouse (2) is built on a submerged reef in the middle of the Long Island Sound, about halfway between Connecticut and New York. It is on the National Register of Historic Places, accessible only by boat, and the property contains "an active Aid To Navigation (ATON)" that "will remain the personal property of the US Coast Guard," the GSA says.

The Keweenaw Waterway Lower Entrance Light (3) is located at the southern end of the Portage River in Chassell, Michigan, at the end of a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers breakwater. "The lighthouse stands 68 feet tall and contains approximately 1,000 square feet of interior space," the GSA says. It was built in 1919 and is now available for purchase through public auction "due to the previous steward's inability to comply with the requirements of the National Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000."

The Cleveland Harbor West Pierhead Light (4) is located at the entrance of Cleveland's harbor and is accessible by boat only. The lighthouse tower is 50 feet high and dates back to 1911. "Own a piece of maritime history with a view of the Cleveland skyline!" the GSA says.

The lighthouses sold through the NHLPA auctions are only for those included, or eligible for inclusion, in the National Register of Historic Places. The GSA says it typically auctions off non-historic lighthouses with other surplus government property.

What do you get with your lighthouse purchase?

The NHLPA says divested "light stations" include the lighthouse, light tower, lighthouse keeper's dwelling, garages, storage sheds, oil house, fog signal building, boat house, barn, pump house, tram house support structures, piers, walkways, underlying and attached land, and related real property and any associated improvements.

Can you really turn a lighthouse into a vacation home?

Yes, "some of the lighthouses purchased in the past have been converted into private residences by people who want a unique living situation," AP reported. There are a few strings attached, however.

"When a light station is sold through public auction, the new owner has fewer use restrictions" than when the lighthouse is given away to a local government or nonprofit, the GSA notes, but "with both, new owners must adhere to applicable historic preservation requirements and provide [the U.S. Coast Guard] access to maintain any active aids to navigation." The Coast Guard also "reserves the right to continue maintaining active ATONs (aids to navigation) after transferring light stations to new stewards," the GSA adds.

Also, "prospective buyers shouldn't get too deeply invested in any romanticized notions" of a move-in-ready pied-à-terre with a view, Mental Floss advised. "Virtually all require some kind of restoration, from painting to more extensive remodeling, and most do not have utilities. As you'd expect, getting insurance can also be costly."

The lighthouses are "such unusual reflections of our history that it takes a certain kind of person who wants to be a part of that," GSA administrator Robin Carnahan told The New York Times.

What is it like to own a historic lighthouse?

It is, as with any fixer-upper, a labor of love. Sheila Consaul, a communications consultant in Washington, D.C., won the Fairport Harbor West Lighthouse on Lake Erie in Ohio in the GSA's 2011 auction. "I've been renovating it pretty much ever since," she told BBC News in May. Her winning bid was about $71,000 for the two-story, 3,000-square-foot lighthouse, about 20 miles east of Cleveland, and she said she has lost track of how much she has spent turning the 1925 building into a summer home.

Sometimes the call of a lighthouse is closer to a siren's song.

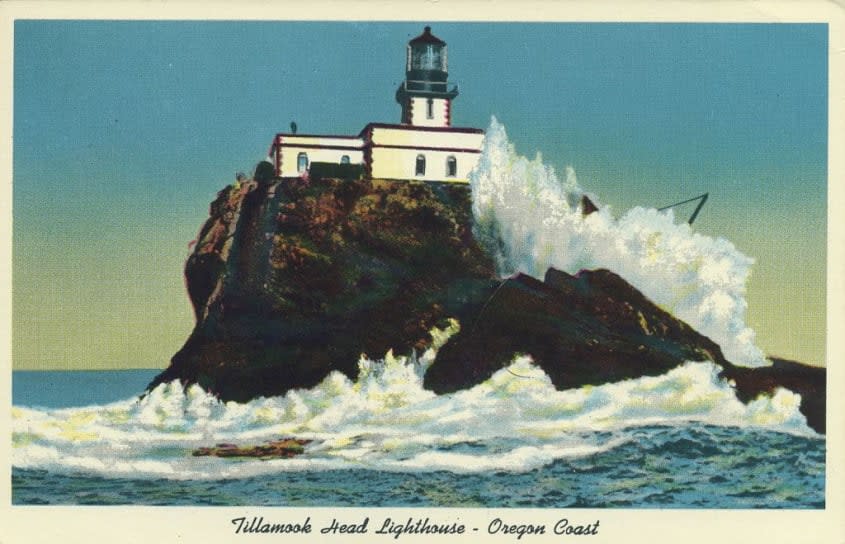

A group of Las Vegas investors bought the historic Tillamook Rock Lighthouse off the northern Oregon coast for $5,600 in a 1959 GSA auction, hoping to turn it into a casino, then sold it for $11,000 to General Electric executive George Hupman in 1973. The Hupman family had to rent a helicopter to get out to the prospective summer retreat, on a small craggy island a mile offshore, then tried to clean up the mess of bird droppings, the Times reported in 2022.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

"Sure, it's dilapidated," Hupman told KGW in 1978. "The paint's peeling off, and it's a mess inside and out," but "that structure's going to be there for a long time, one way or another. And, I don't know, it's an exciting and strong place in midst of a moving and turbulent environment. It gives you a great feeling, being here."

After a few more helicopter trips to the lighthouse, Hupman sold it for $27,000 in 1978, then current owner Mimi Morissette bought it for $50,000 in 1980 and turned it into a columbarium, or place to house funeral urns. "I didn't want to be in the cemetery business, but there is no fresh water, no sewer, no light and no way to land," Morissette told The Oregonian in March. James Gibbs Jr. one of the last Coast Guard keepers of "Terrible Tilly" in 1944, wrote in his memoir that "everywhere I looked, the place took on more of the aspects of an insane asylum instead of what I had pictured a lighthouse to be."

Morissette put it up for sale in 1993 and again 2022, asking for $6.5 million and volunteers to fly out and clean up the lighthouse beforehand, including helping "evict the sea lions that have knocked in the corroding front door." A five-person team of volunteers finally went out to paint and clean up the 1881 lighthouse in March, the first visit to the rock since 2019. "She calls to me," said volunteer Brian Coulson, who has a tattoo of "Tilly" on his left arm. "The conditions are so harsh. She was impossible to build, maintain or even remain ... yet she exists."

At least two people working on the lighthouse fell to their deaths, in 1911 and 1979, and locals have reported seeing paranormal activity at the lighthouse, but "even people that are afraid of the ocean can't help but daydream about 'Tilly,'" Liz Scott, the outreach manager at Cannon Beach History Center, told the Cannon Beach Gazette.

Back at the Fairport Harbor West Lighthouse, Consaul had to install electricity and toilets — it took nine years to get running water to the lighthouse — and since it doesn't have a dock, she often has to lug groceries and other supplies down to the building along a narrow path, she told the Times, but her "very long journey" has been worth it. "There are some amazingly incredible views, as well as history and intrigue," she said. "All of those things people think about lighthouses are true."

You may also like

4 things to consider when leaving an inheritance