Buy now, pay later delinquencies could get 'dangerously' high. What will companies do about it?

Corrections & Clarifications: Updates to the story clarify that the “buy now, pay later” company Affirm will consider tightening lending standards for customers beyond just the riskiest —but on a case-by-case basis — over the next six months.

The story also mischaracterized the profitability of “buy now, pay later” companies. Klarna, one of the companies, was profitable up until 2019.

More Americans are turning to buy now, pay later apps to afford everyday necessities, but an increasing share of consumers aren’t making payments on time, a trend likely to accelerate as the U.S. economy inches closer to a recession.

Traditional lenders, like banks and credit card companies, automatically dial back lending particularly to riskier borrowers when delinquencies inch up to limit future losses. But experts are divided on whether buy now, pay later firms will do the same based on whether they’re prioritizing user growth or profitability.

One thing is crystal clear: If online lenders fight rising delinquencies, many users will have few – if any – financing alternatives as they face the highest inflation rate in nearly 40 years.

Medicare Part D: Where you live can have a big impact on what you pay for drugs

Inflation in the USA: How the pandemic and war reshuffled the prices Americans are paying

How does buy now, pay later work?

Buy now, pay later, a relatively new but rapidly growing industry is an attractive option for younger, typically lower-income consumers who either don’t have a credit history or don’t have a high enough credit score to qualify for traditional credit offerings.

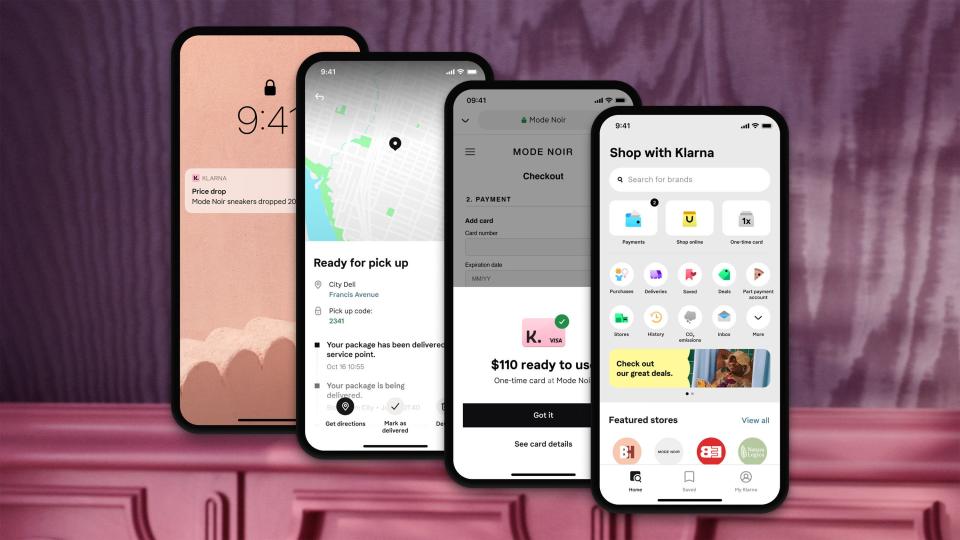

Buy now, pay later companies, which include Affirm, Klarna, Afterpay, Zip and Sezzle, typically require users to make a down payment on an item. The balance is split into three equal, interest-free payments due every two weeks over the course of six weeks.

In some cases, companies allow users to set up longer-term payment plans for which interest is charged. The annual percentage rate could be as high as 36% with Afterpay and Affirm or 25% with Klarna.

At an APR of 20%, a six-month buy now, pay later loan for an item costing $200, the monthly payment would be $35.30 and a total of $11.83 in interest.

Average credit card rates currently hover at 18.79%, according to Bankrate. These rates vary by consumer and are higher for riskier borrowers.

Food for thought: More people are paying for groceries with buy now, pay later apps as inflation pinches

Buyer beware: Buy now, pay later models are gaining popularity. What are the risks?

Buy now, pay later firms don’t have to report late payments to credit bureaus, unlike banks and credit card companies.

Consumers benefit when late payments aren't reported since a late payment won’t necessarily harm their credit score but on the flip side, on-time payments don't boost credit scores or contribute to credit history.

Buy now, pay later companies have no way of knowing a consumer's debt load at competing companies or whether they’re making payments on time.

“They're kind of flying blind,” said Marshall Lux, a research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Delinquencies and charge-offs on the rise at buy now, pay later firms, eating into valuations

During the pandemic, delinquencies at buy now, pay later firms dropped as consumers were flush with stimulus money they used to pay off debt and build savings. But when stimulus payments stopped and inflation skyrocketed delinquencies piled on.

In November 2021, Affirm was valued at $45 billion. As of Oct. 6, it was valued at just $5.4 billion, an 88% decline. Klarna experienced a nearly identical devaluation and laid off 10% of its workforce earlier this year.

Klarna, which is privately owned, doesn’t disclose delinquency or charge-off rates. But a company spokesperson noted their default rate is under 1%. The spokesperson said Klarna is continually reevaluating its lending criteria and will sometimes lend less to new consumers since it is more challenging to predict whether they'll pay on time.

How to get a refund: Buy now, pay later refunds on apps like Afterpay, Affirm, Klarna frustrate consumers

Should users be worried about high debt?: Buy now pay later apps are beloved by consumers

At Affirm, 2% of outstanding loan dollars held on the company’s balance sheet were 60 or more days late as of June, up from under 1% a year earlier. Charge-offs, loans that are at least 120 days late that the company doesn’t expect to be repaid for, have grown tremendously. For the company’s fiscal year ending in June, charge-offs totaled around $228 million, or 3.5 times as much as the prior year.

Affirm’s president of technology and risk operations, Libor Michalek, told USA TODAY that he’s satisfied with the company’s delinquency levels.

Riskier customers could see higher down payments and shorter repayment lengths. But Affirm doesn't expect to make changes to its underwriting model across the board in the next six months, Michalek said. Rather, it will vary on a case-by-case basis.

For instance, "when people get to a point where they are no longer able to responsibly purchase, we will tell them ‘no’ and if they have trouble paying back and contact us, we’ll work with them to ensure they can meet their obligations," he said.

Affirm underwrites every transaction, Michalek said, meaning that it sets lending terms for each buy now, pay later purchase based on a customer's likelihood of making on-time payments. They also set limits for how much money a customer could borrow at once.

Meanwhile, at Block-owned Afterpay, over 4% of outstanding loan dollars were 60 or more days late, compared to under 2% a year earlier, according to Block’s most recent earnings report and data from a recent Fitch Ratings report.

Amanda Pires, a company spokesperson declined to comment on whether the company is exploring stricter lending requirements to limit delinquencies. She pointed out that 95% of payments are made on time.

To put this in perspective, credit card delinquencies have risen from last year but on a much smaller scale than buy now, pay later firms. Delinquencies in the second quarter of this year were 1.8%, compared to 1.6% a year earlier, according to Federal Reserve data.

Michael Taiano, a senior analyst at Fitch Ratings, said the diverging delinquency growth rates are a reflection of buy now, pay later's focus on lending to subprime borrowers that credit card companies would turn down.

A July report he co-authored found that buy now, pay later users carry more debt and have worse credit scores than the general population.

Apple Pay in 4: Apple Pay Later is coming soon to iOS 16. What you need to know about buy now, pay later option

A recession is now likely in 2023: Here's what could trigger a sharp downturn in the economy

Dilemma: user growth versus profitability

Since buy now, pay later kicked off after the 2008 recession, the emphasis has been on user and merchant growth.

But now investors demand profitability, said Hugh Tallents, senior partner at management consulting firm cg42. None of the major stand-alone buy now, pay later companies —including Klarna, Affirm, Afterpay and Zip — are currently profitable, according to Payments Dive.

“One of the biggest things that corrupt profitability in the finance space is delinquencies,” said Tallents. “So they’re going to have to be more judicious about credit checks and approvals,” he said, adding that “otherwise they’re going to end up in a very dangerous circumstance.”

Buy now, pay later firms could also start to levy more hidden fees and charges to compensate for their losses, he said.

“People who have become very accustomed to using BNPL are going to be at risk of a lot of different fees and charges creeping into their lives that they hadn't necessarily expected,” said Tallents.

Some of those fees could include a “repeat user fee” for people who use buy now, pay later loans multiple times a month, he predicted.

That’s a stark contrast to the customer-centric marketing approach many buy now, pay later firms have taken to challenge the credit card industry which is notorious for having complicated hidden fees and charges.

If a buy now, pay later company wants to maintain its “cleaner than clean image” and not slap on more fees, they’re going to have to start declining boatloads of customers, Tallents said. “And unfortunately, that's going to be people who have become habitually used to using BNPL for things that are part of their day-to-day as opposed to one-off purchases.”

Unlike credit card companies, buy now, pay later hasn’t been thoroughly tested through a recession when savings drop and consumers must be more frugal with their money.

Financial stress likely will continue to draw more customers but at the expense of more delinquencies, said Harvard’s Lux who worked as a chief risk officer for Chase at the height of the Great Recession.

“Ironically, it’s precisely the time when these companies need to pull back that they may not do it,” he said since that would mean losing customers they spent years courting. Even with more investors demanding profitability, buy now, pay later won’t want to risk growth in the end, Lux predicts.

“You're going to have the classic case of the risk managers saying, ‘We really need to do something,’ and the marketing staff saying, ‘We need to grow.’”

“This train’s just going to keep marching on,” he said, referring to delinquencies.

Elisabeth Buchwald is a personal finance and markets correspondent for USA TODAY. You can follow her on Twitter @BuchElisabeth and sign up for our Daily Money newsletter here

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Buy now, pay later delinquencies are rising as inflation boosts demand