ByGone Muncie: The city's Black history is strong, vibrant and visible

Of all decades in Muncie’s history, I find the 1890s most fascinating. So much occurred in those 10 years that it’s hard sometimes to piece it all together coherently.

After the discovery of natural gas in 1886, Delaware County, like the rest of east-central Indiana, experienced rapid industrialization and population growth. The boom was short lived but reshaped everything. By the time the Trenton gas field was depleted in 1910, Muncie had become a different place with a new economy.

The growth was nowhere more evident than in the city’s Black community.

The 1880 United States Census recorded 187 African Americans living within city limits. But by the end of the boom, the community had grown to more than 1,000.

Muncie’s overall development in the 1890s was unique.

Outside of east-central Indiana, the rest of the United States slogged through the decade in a nasty economic depression. Muncie didn’t escape it unscathed, but the dwindling supply of cheap natural gas kept the local economy going relatively strong.

The boom maintained a demand for skilled and unskilled labor, attracting new residents from across the Midwest and Upper South. Jobs remained plentiful in manufacturing and construction, as well as retail, transportation and service. Hundreds of African Americans from rural Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina moved to Muncie in the 1890s as a result.

Historians Hurley Goodall and Elizabeth Campbell wrote in 2004 that “job opportunities, along with family and friends already in Muncie, brought in more Black residents who continued to cluster on the city’s near southeast side, forming the early core of the Industry Neighborhood.”

Black Munsonians during the boom also lived in the east end and bought lots in the new Whitely suburb.

“Indiana’s African Americans had begun to urbanize,” according to Goodall and Campbell, “and Muncie had become one of their favored cities.”

Many Black Munsonians found work at Ball Brothers Glass Manufacturing, including Enoch Fletcher and two of his sons, Grant and Zeller. Enoch was a veteran of the Civil War, having served in the 12th Regiment of the U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. The Fletchers moved to Muncie early in the boom and lived at 502 E. First St. in Industry.

Fletcher's other son, Lazarus, was the first African American letter carrier in Muncie, having been hired in 1892. The Muncie Morning News described the postman three years later as “one of Uncle Sam’s most efficient mail carriers.”

Lazarus married Edna Curtis in 1896, and the couple bought a house at 1003 E. First St. in Industry. His sister, Mary, was one of 25 Muncie Central graduates in 1894. At the diploma ceremony in the Wysor Grand Opera House, Mary gave a speech titled “Art of Oratory.”

Just like Mary’s father, Enoch, King Solomon Outland worked at Ball and was a veteran of the Civil War. Outland had fought in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, an all-Black regiment in the Union Army. Outland lived with his son, Jason, at 717 S. Plum (now Pershing) St. He died young at 53 in 1894 of typhoid fever. His obit noted that he was a member of the Williams Post of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization for Union Civil War vets.

Like most predominantly white American cities in the Gilded Age, Muncie was bigoted and segregated. But not so at the G.A.R.’s Williams Post No. 78. War vets, both Black and white, met together in a special Delaware County Courthouse room, exclusively set aside by commissioners. Most G.A.R. members were ardent Republicans, aligned in principle and forever loyal to the party of Lincoln, Douglas, and Grant.

Muncie’s G.O.P. during the boom was well connected at a state and national level. Frederick Douglass spoke here twice, once in 1880 and again in 1888. Benjamin Harrison visited the city three times during the era, including in 1890 when he was president.

Many of Muncie’s Black residents at the time supported the Republican Party and were politically active.

W. H. Stokes was one such leading politician in '90s. A graduate of Wilberforce University, Stokes moved to Muncie in the late 1870s and made a name for himself. He was part of the delegation welcoming Frederick Douglass in 1880.

A year later he became a Center Township justice of the peace.

On the eve of the boom in ‘85, Stokes opened the National House Barbershop on South Walnut Street, one of several Black-owned shops in Muncie during the ‘90s. Stokes' brother, William T., became the city’s first Black police officer in 1899.

The community also had an active religious life during the late 19th century.

In the years before the boom, Black Munsonians established Bethel A.M.E. in 1868 and Second (Calvary) Baptist in 1872. The 1893 Emerson City Directory lists Jason Bundy as pastor of A.M.E., while John Broyles filled the same role at Second Baptist.

Some Black Munsonians in the 1890s joined fraternal and sororal lodges, including Gas Belt Lodge No. 3012 of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows and Widow's Sons’ Lodge No. 22 of the Free and Accepted Masons. Widow’s Sons met at the Willard Block just north of the Patterson Building, as did their women’s auxiliary, Naomi Chapter No. 11.

Jacob Gillenwater was the lodge’s worshipful master in 1894. He worked at Hemingray Glass and lived with his wife Annie in Whitely. Other lodge officers that year included Al Shoecraft, postman Lazarus Fletcher, and Felix Harreld.

Harreld was the maintenance supervisor for the Anthony Building in the 1890s. Part of the Anthony still stands today at the northwest corner of Walnut and Jackson. In 1887, Harreld helped coordinate Muncie’s city-wide Emancipation Day celebration. He lived with his wife, Ellen, and son, William Kemper, in a downtown apartment at the Bishop Block.

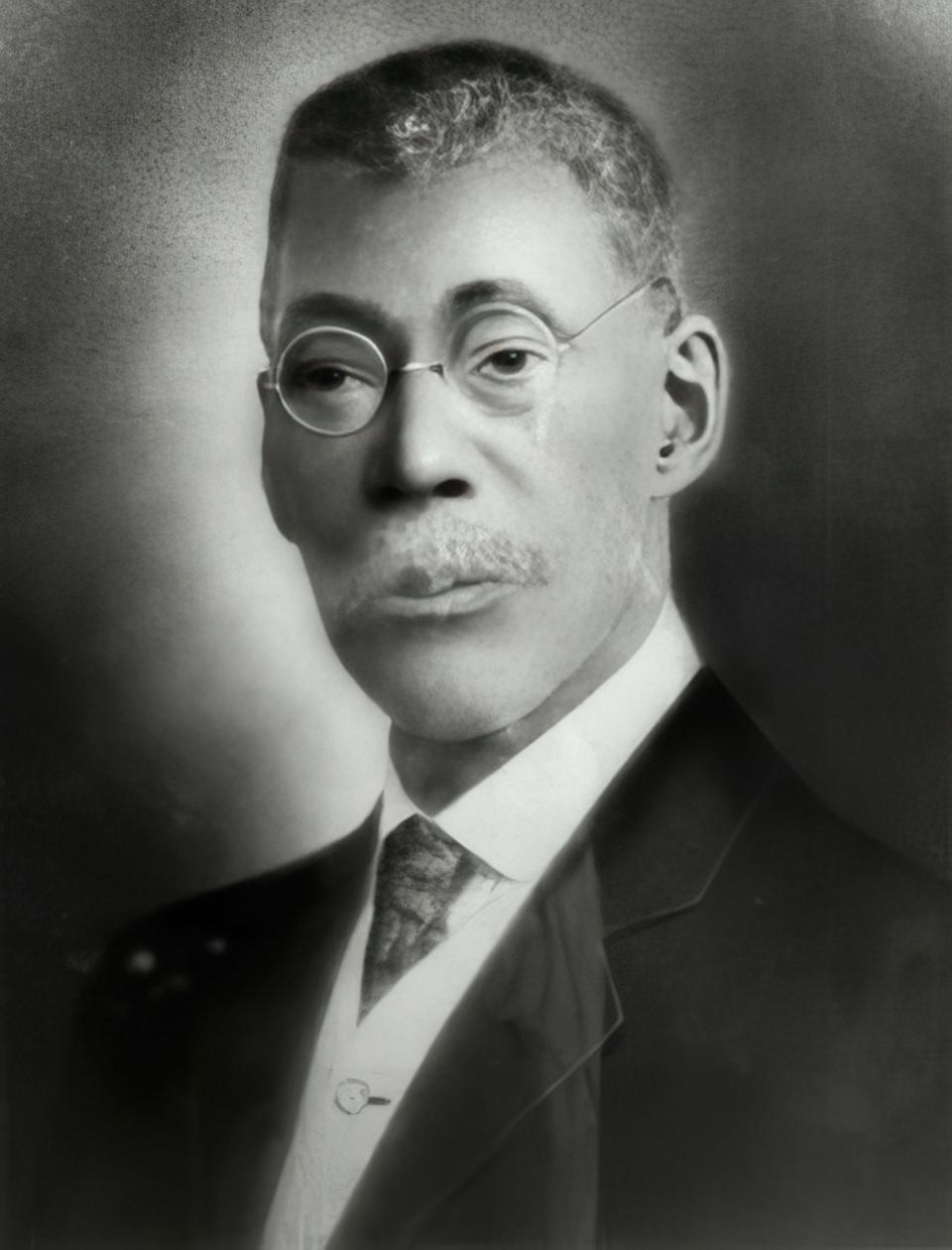

The Harrelds’ son, William Kemper, became a celebrated violinist and pianist.

After studying at Muncie Central, Kemper attended Chicago Musical College in 1904. In 1911, he became director of music at Morehouse College in Atlanta and was the founder of both Morehouse and Spelman college glee clubs.

This is only a fraction of Muncie’s Black history in the 1890s. African Americans continued to move to the city after 1900 in large numbers, forever influencing the city’s evolution. By the turn of the century, historians Goodall and Campbell rightly concluded that “Muncie’s African American community … had grown strong, vibrant, and visible.”

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: Remembering Muncie's strong, vibrant and visible Black history