ByGone Muncie: Keesling vs. Muncie Pulp Co.

MUNCIE, Ind. ‒ You probably read a few weeks ago about the abrupt end of the Michael’s Place development in southwest Muncie. In a win for local journalism, the $52 million project was ditched after The Star Press inquired about the developer's history of fraud.

The project is the second unsuccessful real estate venture at the southeast corner of Memorial and Tillotson. About 20 years ago, the Westwind Village housing project failed at the same location. If you’re unfamiliar with the whereabouts, both developments were planned for the trapezoid of land running east of Tillotson to Brookfield Terrace and south of Memorial to Buck Creek.

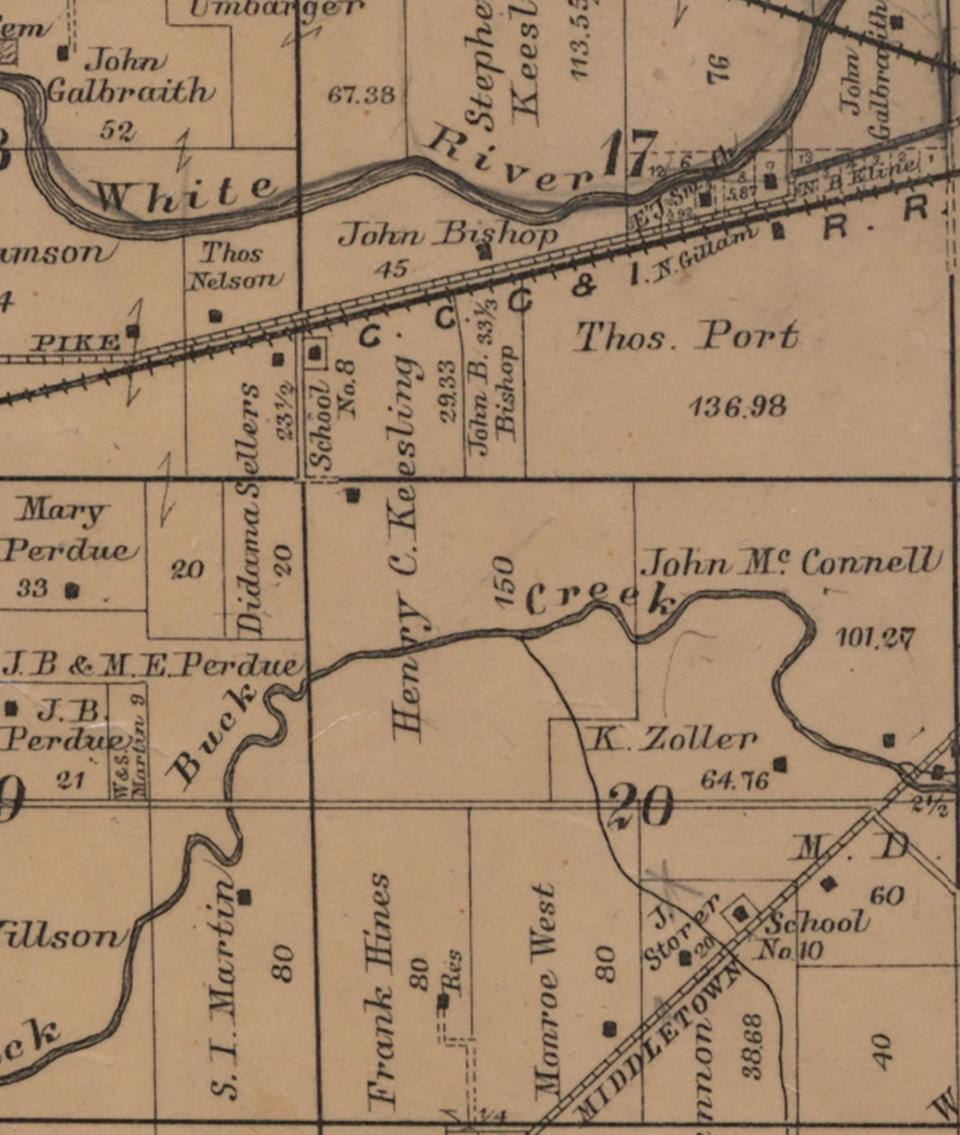

The area was mostly farmland prior to the 21st century. From the 1870s through the early 1920s, it was part of Henry Keesling’s sprawling Center Township estate. Born in nearby New Burlington, Keesling moved to Muncie sometime after the Civil War and either bought or inherited acreage stretching south from what is now Memorial Drive to Cornbread Road. He later bought tracts north, enlarging his farm to Kilgore and the Big Four line (CSX).

At the time of his death in 1923, Keesling’s estate consisted of 4 horses, 24 head of cattle, 60 hogs, 6 tons of hay, ~50 bushels of corn, a flock of leghorn chickens, and a Ford Roadster with demountable rims.

Keesling appears frequently in the local historical record, although sometimes for odd reasons. In 1903 for instance, the Muncie Morning Star reported that he was “attacked by a vicious heifer” on a neighboring farm. Though Keesling was “old and infirm, he made a strong fight,” beating back the beast with his ax.

Then in July of 1909, Keesling lent a 1,600 pound bull to fight a French strongman named Athos. The latter had come to Muncie for a bullfight at Westside Park. According to the Star, Keesling’s rancorous ox had the “reputation of the worst kind in the city.”

On the day of the battle, however, the bull “refused to become excited and acted like he wanted to be petted.” A crowd of 600 angry Munsonians felt swindled and rabbled to toss the Frenchman into the White River. Athos was saved at the last minute by two stalwart MPD officers.

Violent bovines aside, Keesling is mentioned most often in the record for his lawsuit against Muncie Pulp Company. Along with industry counterparts at Consumer Paper in Westside and at West Muncie Strawboard in Yorktown, Muncie Pulp dumped tons of poisonous chemicals into local waterways during the gas boom.

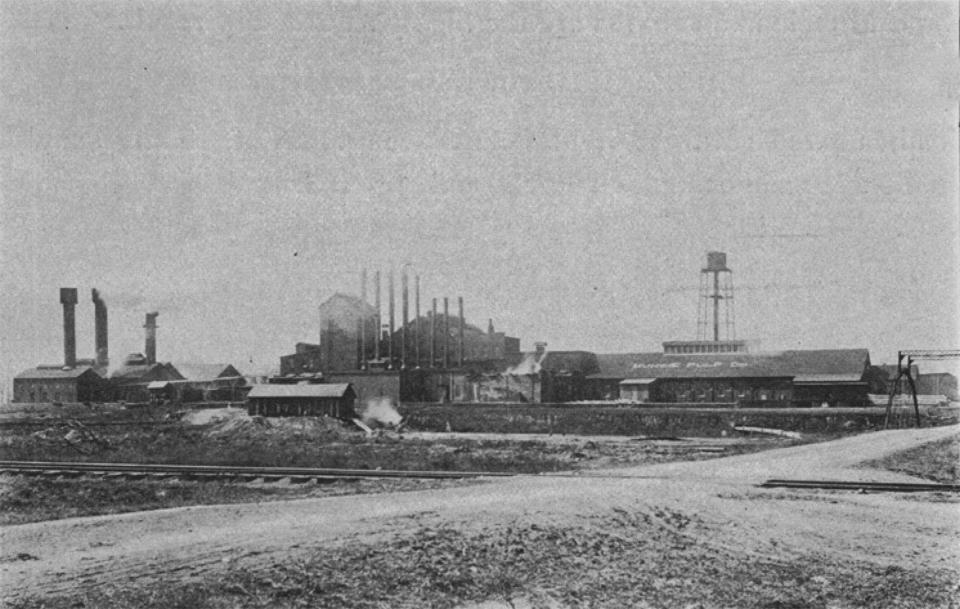

Their pollution trashed several farms downstream in Center and Mount Pleasant townships. Buck Creek, one of White River’s primary tributaries in Delaware County, flowed through the middle of Keesling’s farm. Muncie Pulp’s mill sat upstream in Congerville, south of the three-way intersection of Gharkey and 23rd streets.

In early February of 1901, Keesling sued Muncie Pulp for $10,000 in damages ($350,000 in 2023 dollars). According to the Evening Press, the Buck Creek once supplied valley farmers with clean water, “but since the pulp and strawboard companies have been dumping their refuse into it, the water has been made filthy and unfit for stock to drink.” Keesling was out for blood and “says that he proposes to fight the case” to “make the pulp company’s business unprofitable.”

Keesling wasn’t the first Delaware County farmer to sue Muncie Pulp. Samuel Martin sued in May of 1898, claiming MPC ruined his farm. He was later awarded $2,000 in a civil judgment. Jeremia Wilson sued five months later, maintaining his fields were “rendered worthless as far as producing crops.”

However, it was Keesling's February 1901 lawsuit that opened litigious floodgates. Julia Mueller sued Muncie Pulp for $5,000 on March 1, claiming the “poisonous refuse from the pulp mill has overspread her fertile farm, making it useless for growing grain and valueless as a commodity.” Mueller’s suit also asserted that her cows refused to drink the putrid Buck Creek waters and “that fish in the stream have been killed.”

By month’s end, a dozen farmers living along the White River and Buck Creek had filed similar suits: James Williamson, Frank Luce, Samuel Grice, William Wiggerly, Edward Pullin, Sara Harmon, and Hannah Painter all sued Muncie Pulp, while Joseph, Charles, and Jane VanMatre, Arthur Wiggersley, Alexander Muller, and David Campbell sued Consumer Paper and West Muncie Strawboard.

Headquartered in New York City, Muncie Pulp first began local operations in May of 1888, two years into the gas boom. The company was formed to commercialize Henry Blackman’s chemical process of breaking down cellulose to make pulp for paper production. Local farmers initially loved Muncie Pulp, as the mill bought up everyone’s straw.

However around 1890, MPC abandoned it because too many weeds mixed in with the bales. They switched to cottonwood trees harvested from timberland near the Mississippi River.

I get the impression from 1890s newspapers that, at first, Muncie Pulp dumped grimy chemical water directly into Buck Creek. Consumer Paper, located at what is today Payless Supermarket off Tillotson, discharged into the river at Westside, while West Muncie Strawboard dumped into the river at a location now home to Yorktown’s Middle and Elementary schools. After the flurry of 1901 lawsuits, all three mills installed settling pools to filter out the chemicals. But when the Buck Creek or White River spilled their banks in heavy rains, floodwaters collected the contaminated pools’ contents and sent them downstream.

In October of 1901, after an investigation and despite public outcry, Indiana’s State Board of Health issued operating permits for all three paper mills in Delaware County to continue discharging waste. The Evening Press published a statement from the board’s president, “we are not responsible for what these mills did before we issued them permits.” The statement concluded, “these mills are a source of great commercial value to Muncie and the whole of Delaware county, and the board does not propose to do anything to cause their removal.”

Most lawsuits were settled out of court for unreported sums, though Keesling refused to settle. After requesting a change of venue, his case was argued in front of a Randolph County jury in April 1903. Jurors found Muncie Pulp culpable and awarded the farmer $4,000. MPC appealed the decision all the way to the Indiana Supreme Court, which in December 1904, affirmed the lower courts’ rulings against the company.

Alas, Muncie Pulp was bankrupt by that time. The settlements, civil judgements, and legal fees sent the company into receivership. The Evening Press concluded, “it is doubtful if Keesling will be able to recover anything near the amount of the judgment.”

Keesling, however, achieved a far greater and more noble ambition, one worthy of historical recognition: the ruination of one of the worst gas boom-era polluters of the Magic City.

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Muncie Star Press: ByGone Muncie: Keesling vs. Muncie Pulp Co.