ByGone Muncie: Levees worth our gratitude

MUNCIE, Ind. – “It began to rain terribly again. In the evening all the land along the river was already under water and during the night, there was such a flood as we had never before seen here, and even the oldest inhabitants along this river could not remember anything like it.” - Abraham Luckenbach and John Peter Kluge, March 9, 1805.

Luckenback and Kluge were Moravian missionaries living two centuries ago in what is now Madison County. Their diaries documented life along the upper White River from 1801-1806, including dreadful spring storms in May 1804, March 1805, and May 1806. Subsequent flooding destroyed their fields and fences, along with some of those of the Lenape, Shawnee, Myaamia, French-Canadian trappers, and American squatters living in the area.

Although, flooding at this time is best understood as a relative concept. Natural wetlands and floodplains overlayed large swaths of east central Indiana for millennia, beginning at the end of the last glacial period some 18,000 years ago. This ecosystem began to change significantly in the 17th and 18th centuries as trappers annihilated the beaver population. The Indiana DNR estimated that 5.6 million acres of wetlands sprawled across what is now Indiana prior to 1780. 85% of this was drained in the past 242 years for “farms, cities, roads, and to protect human health,” according to Indiana’s Department of Environmental Management. 813,000 acres is all that’s left.

Enough wetlands remained in 1881 for historian Thomas Helm to estimate that 20% of Delaware County was prairie, “generally of the class known as wet prairies.” Frank Haimbaugh noted in his 1924 history that “a considerable section of the county was in its natural condition poorly drained and unfit for agriculture.”

Undaunted, settlers and their descendants dried most wetlands for farms between 1830-1900. Residential neighborhoods and suburban sprawl took the rest. During heavy rains, local rivers and creeks disregarded development as they swelled and spilled into timeworn floodplains. As a result, Munsonians faced major flooding well into the 20th century.

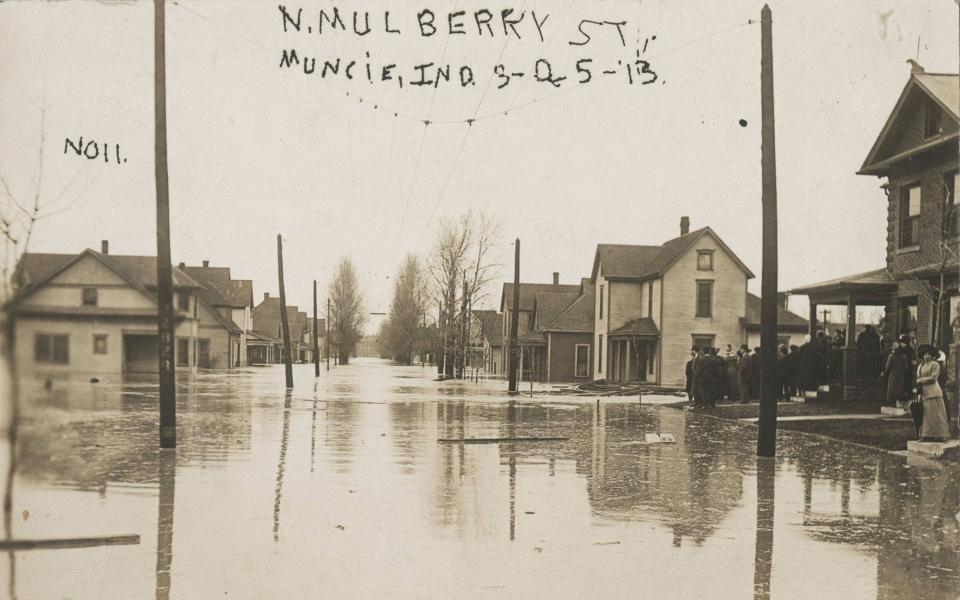

The worst deluge in local recorded history occurred in late March of 1913. Known generally as the Great Flood of 1913, torrential spring rains triggered widespread flooding across the Midwest on Easter. The Muncie Star estimated that five inches of water fell across the city on Sunday, with the White River “rising at a rate of eight inches an hour.” Interurban and train lines were wrecked as municipal sewers clogged. Most of the land in the river bend, today McKinley Neighborhood and Muncie Central but known then as Wysor’s Bottoms, was “covered with several inches of water.”

The rains continued through Monday. The Evening Press reported that “Eastern Indiana is being swept by a deluge of water. Traffic is tied up, the roads are impassable in many instances and train schedules are being altered or abandoned.” Muncie’s earthen levees held intact for the moment, but “in many parts of the city, cellars are filled with water, some of them for the first time.”

A wet hell broke loose early Tuesday morning to trash the Magic City. The Press wrote that the “White River, like a tawny haired plant breaking its bonds, crept from its banks last night carrying everything before it. Around the entire city, from Westside park, which is submerged, through to the Indiana Steel and Wire mill on the east, the river has become a yellow, angry torrent.”

Around 1:10 am, “a strip of the North Walnut street levee, 100 feet wide, gave way.” Another section failed about 20 minutes later, pouring “tons of black water into the low north section of the city.” Around 3:00 am, “the water broke over Wheeling avenue and rushed into Riverside.” City workers scrambled to shore the remaining earthworks, “all the city dump carts were called into service and ton after ton of dirt and stone were hauled to the low places.” But the effort failed, “the big levee running from Madison street to the Lake Erie and Western Railroad was overridden at 7:16 am.” The White River would eventually crest at 22.6 feet (flood stage is 9 feet).

It all happened so quickly that Munsonians scrambled to save stranded neighbors. “Wagons, boats, cabs and everything of a rescuing nature was pressed into service.” Hundreds “were taken from their homes, some from the second story windows, some from the roofs and others from telephone poles and trees.”

Watchmen closed the Whitely (Wysor), High Street, and West Jackson bridges after their lower decking became submerged. The flood swept away the East Jackson Street bridge at 11:00 am, followed by the Chesapeake & Ohio and Pennsylvania railroad bridges about noon. A High Street bridge watchman named Jack Maddox was “swept into the river while attempting to protect the bridge” from debris. His corpse was found two days later in Chesterfield. So far as I could find, his death was Muncie’s only one. Other cities fared worse. 360 people drowned in Dayton alone. Two dozen died in Peru, along with hundreds of circus animals.

The river began to recede Wednesday morning. The Star reported $100,000 in damages ($3 million today). The destruction to the railroads comprised the bulk of the loss, along with Muncie Water Works, Indiana Steel and Wire, and Muncie Electric Light. Hundreds of residents were also affected, where “two hundred homes in the north end of Muncie and 100 more in Normal City and Riverside have been damaged by the dirty, murky water.”

The Great Flood of 1913 devastated many communities across the eastern United States, prompting public outcry for federal flood controls. The Democrats made it a plank of their platform in the 1920s, which became policy under President Roosevelt a decade later. The feds began construction of new Muncie levees in the 1930s. The system was completed by the Army Corps of Engineers around 1950.

As I reflect on what I’m most grateful for this Thanksgiving, Muncie’s levees make the top of the list. As the full weight of climate change descends upon us this century, flooding will become an ever increasing hazard for Muncie. The levees are all that stand between us and catastrophe in the epic storms to come.Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Muncie Star Press: ByGone Muncie: Levees worth our gratitude