ByGone Muncie: The resurrection of John Johnson

MUNCIE, Ind. – Early morning on Sept. 27, 1892, two Monroe Township fieldhands named Harvey West and John Conway set out for work down the Walnut Street Pike. Like most of rural Delaware County, the countryside near Cowan along Buck Creek was busy that fall with the harvest. West and Conway planned to spend the day cutting corn nearby on the farm of John Bates.

An old guy walking on the pike stopped the farmers and asked where to find work. The man appeared a little ragged and had a long gray beard, but seemed hardy enough. He said his name was John Johnson. The Muncie Daily Times described him as “penniless but looked like an honest man.” Folks like Johnson seeking seasonal field work were commonplace in fall. The Gilded Age brought many advancements in mechanized farming, but 1890s harvests still relied mostly on animal and human muscle.

Conway offered Johnson work picking corn and the trio headed into Bates’s fields after breakfast. Twenty minutes in, the bearded drifter disappeared. Accustomed to unseasoned newbies, Conway and West just thought Johnson fell behind and continued on. But on the way back, they were horrified to find the man dead, clutching a “bundle of fodder in one arm” and a corn knife in the other, according to the Times.

The farmers called county coroner William Driscoll, who arrived a few hours later and determined that Johnson died of a heart attack. By early afternoon, Johnson’s body turned rank in the late September sun. Monroe Township trustee William Ross collected the remains and hastily buried them nearby in a pauper’s grave at Christian Friend’s Church Cemetery (Fairview Cemetery today). Later that night, a passing farmer spotted men digging at the same spot. The ghouls later left in the direction of Muncie hauling something in a cart. Come morning, wild rumors of body snatching spread across Monroe Township.

Between the 1870s and early 1900s, Hoosier graverobbers plagued rural cemeteries like Christian Friends. The post-Civil War growth of medical schools in nearby Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Louisville created a market for cadavers. Resurrectionists, as they were sometimes called, met demand by stealing the recently deceased. In fall semesters, ghouls often ransacked cemeteries across central Indiana for fresh corpses to sell in Indy.

Back in 1879, the General Assembly attempted to curtail such grisly thefts, while providing legal means for medical schools to obtain cadavers. The Muncie Morning News reported in February of 1879 that graverobbers faced a $2,000 fine and a year in prison under the new law. But for legit medical, anatomical, or mortuary research, legal cadavers could be acquired from “bodies of prisoners if unclaimed for 24 hours and vagrants found dead, and persons killed while committing a felony or escaping the law.”

Turns out, the men who disinterred John Johnson in September of 1892 were just exercising their lawful right. As a “vagrant found dead,” Johnson’s body could be used as a cadaver. When George Edgley and A.E. Whitney of Muncie learned about the ‘available’ corpse near Cowan, they petitioned Driscoll to exhume the body. Late that evening, Driscoll led Edgley and Whitney to Friend’s Church Cemetery and, with help from John Conway, they ‘resurrected’ the body of John Johnson.

Edgley was the director of Ohio Wagon Works on Muncie’s east side. The company produced durable ambulances and hearses. Whitney was the secretary of Muncie Casket Company, a factory near Council Street south of the Big Four (CSX) railroad. Muncie Casket made caskets of course, but also undertaker supplies, steel vaults, and embalming fluid.

In partnership with R. Meeks and Sons mortuary, Ohio Wagon Works and Muncie Casket were hosting an October 1892 conference titled, “Professor Sullivan’s Oriental School of Embalming.” According to the Times, the two-day event welcomed 300 “undertakers from all parts of the United States to hear the lectures and witness interesting object lessons.” The final session was an embalming demonstration led by Felix Sullivan of Boston. Sullivan was famous in posh undertaking circles for embalming Ulysses S. Grant in 1885.

Sullivan needed a cadaver to showcase his process in Muncie, which is why John Johnson’s body was exhumed. The Muncie Morning Star went out of their way to inform readers that the resurrection was legal and humane. Driscoll, Conway, Whitney, and Edgley had “no intent other than to benefit humanity,” the Star gushed. As for Professor Sullivan, his “heart is as tender as that of a child and whose touch is not to harm.”

The paper’s oozing flattery was surely meant to dissuade Munsonian anxieties stemming from an incident that happened two years prior. In August of 1890, Muncie Casket hosted the city’s first embalming school, held then for 40 undertakers in Walling Hall west of the courthouse. In the middle of the conference on August 4, a brick mason working in the building left disgusted because “of a most sickening odor that filled the rooms.” An investigation revealed a “dead man, in a badly decomposed state, occupying the hall at the rear of the building.” George Distelhurst of Muncie Casket assured MPD patrolmen the body was a legal cadaver. He noted cow hides rotting in the basement as the source of the stench.

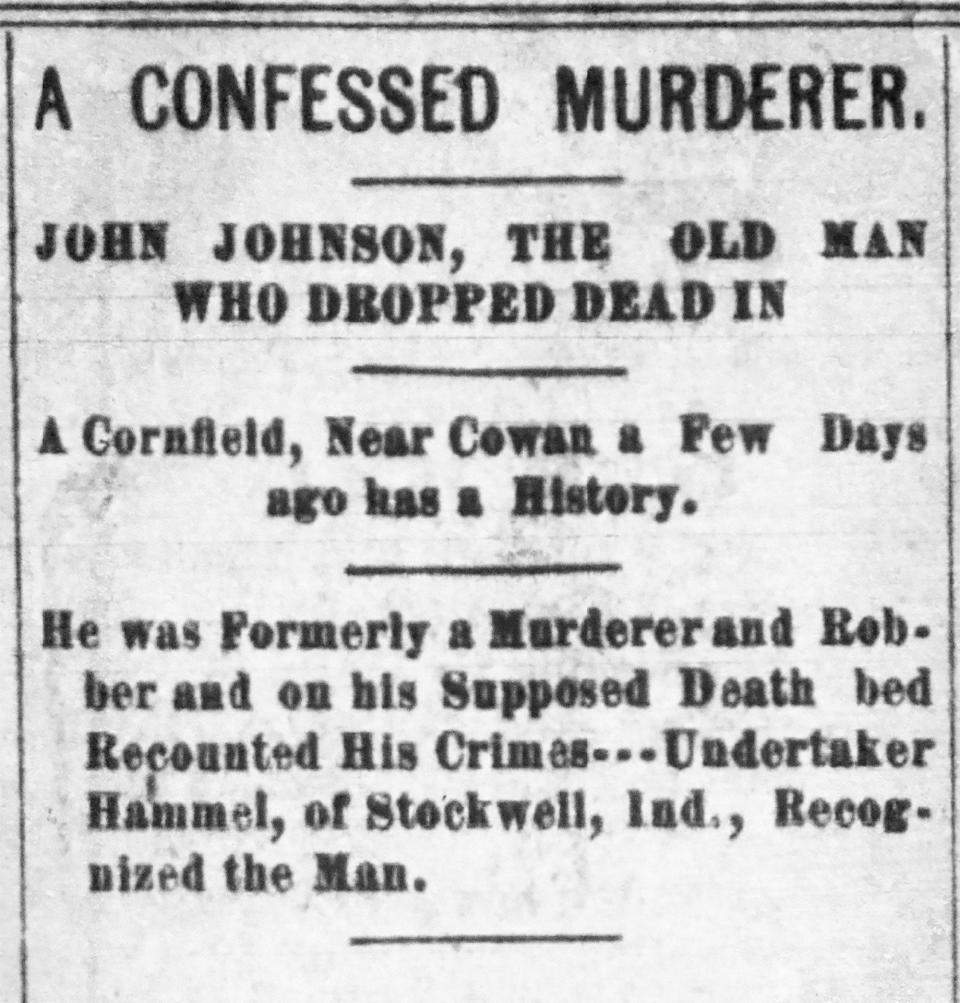

Muncie Casket learned their lesson and didn’t take any chances during the 1892 conference. Professor Sullivan’s embalming demo was held at the Wagon Works way out on Muncie’s east side in Boycetown. As he embalmed Johnson’s corpse in front of hundreds, an undertaker from Stockwell, Indiana named Nathaniel Hammel supposedly proclaimed, “I know that man. It’s Bill Mitchell!” According to the Times, Hammel knew ‘John Johnson’ as William Mitchell, a drifter prone to drink who sometimes lived in the mortician’s barn.

Hammer said Mitchell/Johnson became sick a few weeks prior and, on what he thought was his deathbed, confessed to being a highway brigand in Tennessee during the Civil War. With his brothers and father, Mitchell ambushed and murdered travelers passing near Clarksville. According to the Times, “he himself had murdered one man, his father had shot or stabbed four.” He evaded justice and moved to Indiana after the war.

Mitchell recovered after the confession and fled, fearing discovery of his past banditry. He made his way to Cowan, probably via train. On the morning of September 27, he was walking down Walnut Street Pike when he met Harvey West and John Conway. He died later that morning picking corn under a hot autumn sun.

A week later, hundreds of undertakers returned home from the conference with new knowledge learned from a master embalmer. On October 8, William Mitchell was buried in Beech Grove Cemetery as John Johnson. Four days later, if you can believe it, Ohio Wagon Works burned to the ground.

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: ByGone Muncie: The resurrection of John Johnson