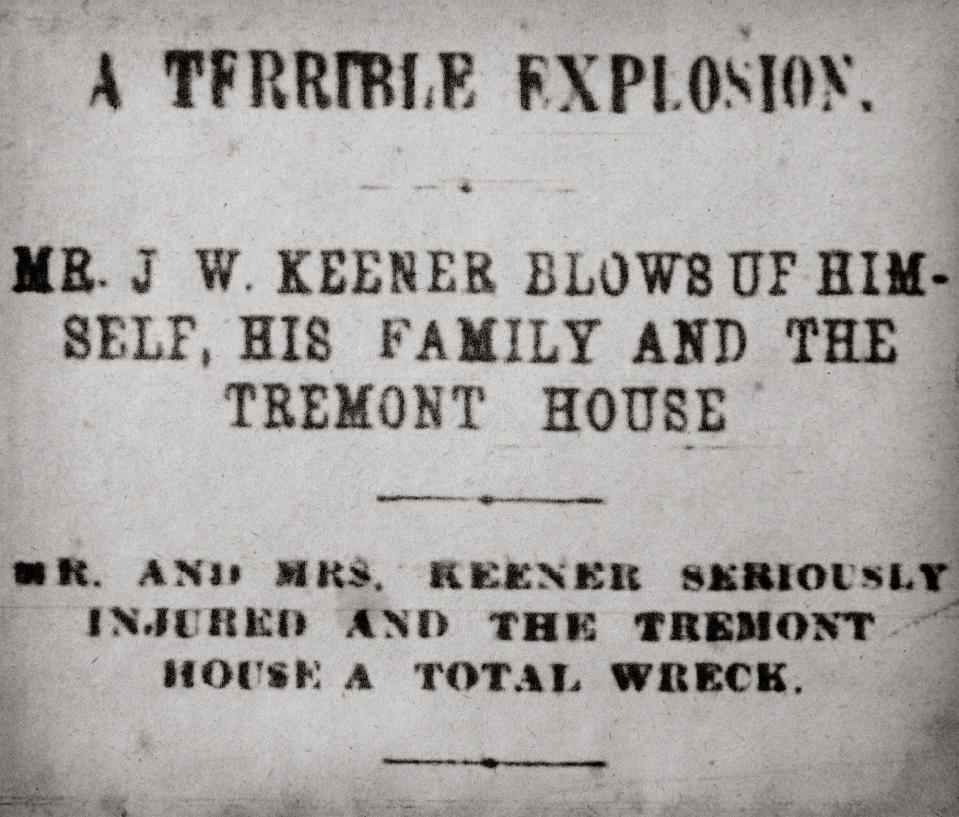

ByGone Muncie: The Tremont House Explosion

MUNCIE, Ind. – A major flood inundated Muncie over Groundhog Day’s weekend in 1883. Heavy sleet on Friday, Feb. 2, gave way to torrents of rain come Saturday.

The White River spilled its banks on Sunday, submerging most of the city’s low-north end under two feet of water. Old timers told the Muncie Daily News that the river had “not been so high since 1847.” Local diarist Thomas Neely wrote, “water is all over Wysor’s bottom ground” causing “a great deal of damage.”

Yet, the flooding wasn’t the craziest story to come out of Muncie that weekend.

At half-past three on Saturday, as pouring rain rendered Munsonians “listlessly dull,” the News wrote that the city “was startled out of its equanimity and sober plodding monotony by a sudden and sharp explosion.” The blast reverberated across downtown, shaking Muncie “to its center and startled the inhabitants into a vague and unknown dread.”

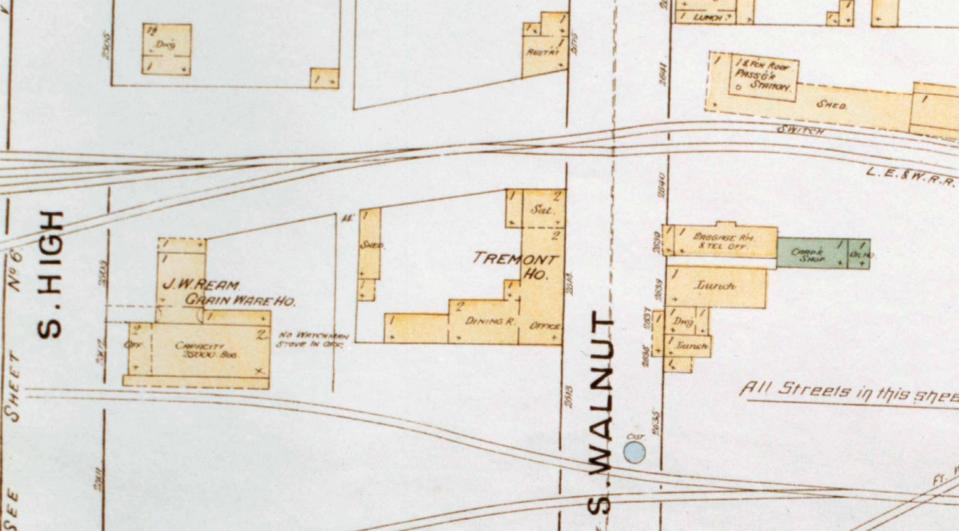

The source of the explosion was the Tremont House on Walnut Street, a two-story tumbledown inn tucked between the Lake Erie & Western Railroad tracks. The Star Press Distribution Center’s parking lot is on the site today, just across Walnut from T&H Sweeper. But on the dreary afternoon of February 3, 1883, the spot was home to the smoldering ruin of the Tremont House Hotel.

Neely recorded the detonation in his diary: “this afternoon, there was an explosion at the Tremont House, a poor hotel near the depot. A man by the name of Keener, a drunken fellow, kept the house and had a small grocery.” Keener “put fire to a can of (gunpowder) and blew out both sides of the house and himself with it. He is badly hurt, but also, his wife. Whiskey did it.”

The rain extinguished the fire, but the Tremont’s blown-out husk swayed in the downpour, threatening collapse. Two brave Munsonians, Martin Mock and John Trego, rushed into the wreckage and pulled out Amanda and John Wesley Keener, the hotel’s proprietors. The couple’s oldest son Quince was also in the building but escaped unharmed.

Amanda was found alive in the front parlor’s rubble, unresponsive and badly injured. She was taken to a house across Walnut “where she recovered consciousness and had her wounds dressed.” The explosion originated in the Tremont’s grocery and had blown out the door into the parlor where Amanda was sitting, violently striking her head.

John Keener was found in the grocery’s remains, “lying on the floor with his feet toward the door of the sitting room and his head under the counter, scratching his blackened and mangled face and clothing.” He was taken to John Shinn’s blacksmith shop across the street. “Mr. Keener’s injuries are very severe,” the News reported. “He was evidently close over the can of powder, and the entire lower portion of his face is blown full of powder.” Terrible burns covered the rest of his body.

Keener initially blamed his family when asked about what had happened, but later professed he didn’t remember. As flood waters rose Sunday morning, he began babbling incoherently about buried treasure. The News wrote that, just before dying midday, Keener “gave particulars as to different amounts of money, buried at various places here, at Yorktown and at Farmland, amounting in the whole to about $2,000,” roughly $60,000 today. Keener’s last words were, “just let the flour be and it will do its work.” His body was given to family and buried in a small Blackford County cemetery.

The explosion and subsequent buried treasure scuttlebutt “created the most profound sensation and all manner of wild rumors are afloat.” Yorktowners went nuts over it. The News wrote, “Yorktown is all torn up over the buried treasure and ghostly midnight prowlers may be seen industriously and secretly searching.”

All evidence pointed to John Keener having deliberately fired the gunpowder, but questions remained. Delaware County’s coroner, David Buchanan, held an inquest to determine Keener’s cause of death. The interviews were conducted at industrialist T.F. Rose’s office in the Patterson Building. The coroner interviewed Keener’s three adult sons, Quince, Charles, and Grant, along with Tremont’s saloon keeper, William O’Meara. All four told Buchanan that Keener behaved erratically before the explosion. Grant was at a doctor's appointment when the Tremont blew, but told Buchanan that he “heard father threaten to kill mother and Quince” earlier that week.

Quince, who miraculously survived the blast unscathed, said he had argued with his father the morning of over family finances. Quince testified that his father was drunk and repeatedly kept going in and out of Tremont’s grocery during the squabble.

However, the most damning testimony came from Charles, who claimed his father had recently “made two threats, one to take powder and blow my damned head off, and the other to take powder and blow us all to hell.” Charles clerked at George Manvell’s liquor store and was there when the Tremont exploded. The night before Keener died, Charles heard his father mutter, “O, I’m sorry I done it, I’m sorry I done it.”

The coroner concluded that John Keener died by “bruises and burns on his person caused by an explosion of a can of powder, ignited by his own hands, while frenzied by excessive and protracted drinking.”

Keener was vulnerable to alcohol, which mixed terribly with whatever mental illness he suffered from. The News wrote that “his mind has been considered somewhat unsettled for some time.” He once ran a successful business in Farmland, but it failed. He sobered up in the late 1870s and gave temperance lectures around Muncie. At a courthouse presentation in 1879, Keener told those assembled that “I have lost two dwellings, two ware-houses, four tracts of land, ten thousand dollars in gold and twenty thousand dollars in currency. A shattered mind and a broken constitution is all that remains…whisky did it all.”

Sadly, Keener fell off the wagon sometime in the early 1880s. Around this time, he and Amanda began managing the Tremont House. Known as ‘City Hotel’ during the Civil War, the Tremont had once been Muncie’s finest inn. But new and better hotels sprung up after the war, including the Abbott, Haines, and Kirby houses. Tremont’s business declined from the competition. Owners rebuilt the Tremont after the 1883 explosion, but the hotel remained seedy for decades. Mayor Rollin Bunch had it demolished in 1914.

Amanda lived until 1898, although no one ever reported finding her husband’s treasure. Perhaps Keener’s hoard lies buried still beneath Yorktown, forgotten in time like the Tremont House and its long dead innkeepers.

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a Senior Lecturer of Media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Muncie Star Press: ByGone Muncie: The Tremont House Explosion