How a BYU-Duke volleyball game became ground zero for race politics

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Michael Irvin, the former wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys, told a simple truth to his national ESPN audience this week.

“In a gym, everybody hears what is being said.”

Irvin was speaking specifically about one gym. The George Albert Smith Fieldhouse at Brigham Young University.

I know it well.

I used to jog its indoor track every morning when I was a BYU student in the early 1980s. It was old and musty even then, built in 1951 for a BYU basketball team that played in canvas high-tops.

Last Friday night, the Smith Fieldhouse became ground zero for race politics in America.

Two universities, BYU and Duke, whose histories are intertwined with this nation’s agonizing history of race, met for a women’s volleyball match that would soon lead to scandal.

BYU and the story of racist doctrine

BYU’s history with race is informed by its founding organization, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Mormons, as they once called themselves, had doctrinally forbade African Americans and other Black people from holding the priesthood.

It was discriminatory and racist, and practiced into the 1970s and continued to shape attitudes within the modern church.

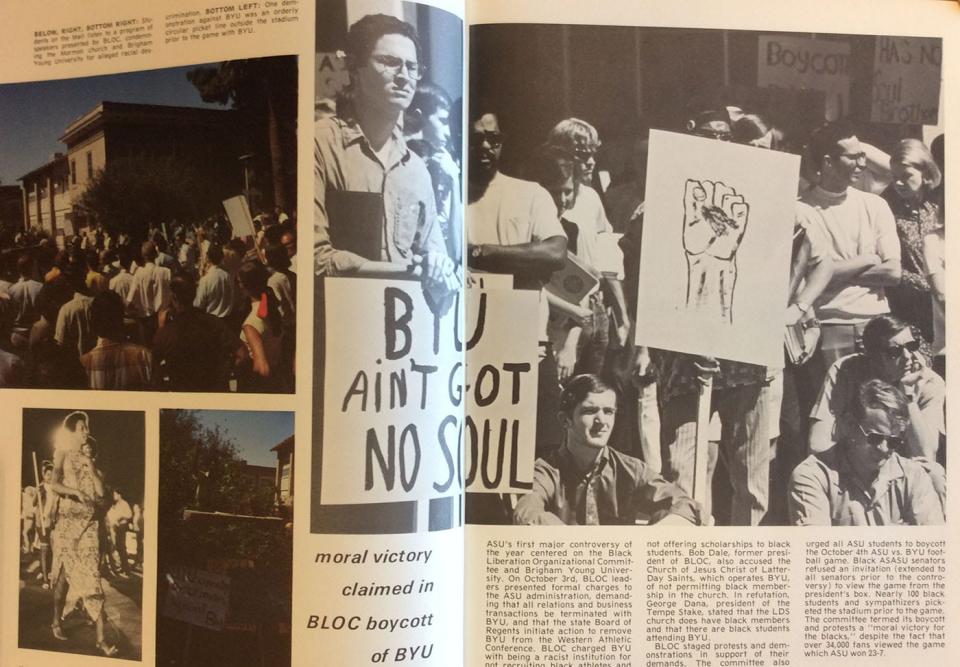

In 1969 a courageous group of African American football players at the University of Wyoming known as “The Black 14” proposed wearing black armbands to the BYU game to protest the policies of the LDS church.

As retold by The Arizona Republic’s Dana Scott, the young men were reacting to what had happened to them the year before when they played in Provo.

How it happened: Protests against BYU teams brought church changes

“Our players were being cheap-shotted by the BYU guys and they were throwing the N-word around,” former Wyoming player John Griffin, one of The Black 14, told Scott. “And then at the end of the game, as the BYU players had exited the field, within minutes the sprinkler system was turned on before our players exited the field.”

For merely asking if they could wear black armbands to protest at the BYU game, The Black 14 were kicked off the team, sign-certain that racism was still a national malignancy.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, attitudes were beginning to change within the church. In 1978, then-church president Spencer W. Kimball announced the prohibition on Black men holding the priesthood would be lifted.

The majority of church members were way ahead of him. They rejoiced.

At the time, a freshly minted Harvard Law and MBA graduate named Mitt Romney heard the news on his car radio, pulled over and wept. His father George, who was governor of Michigan and later HUD secretary, was a strong supporter of the early Civil Rights movement and had marched with his wife, Lenore, side by side with Black Civil Rights activists in the 1960s.

Duke and the story of a racial hoax

Duke’s history with race erupted in 2006 when Crystal Mangum, a stripper and dancer, falsely accused three members of the Duke men’s lacrosse team of raping her. The case was high charged with race because the accuser was Black and poor and the accused were white and affluent, recounts History.com.

Durham County District Attorney Mike Nifong threw the book at the college men, prosecuting them with unusual zeal. About the same time a group of 88 Duke professors took out an ad in the Duke Chronicle (the student newspaper) implying the young men were guilty and that their actions spoke to a larger problem of sexism and racism at the university, something whispered frequently, they said, by their own Duke students.

“These students are shouting and whispering about what happened to this young woman and to themselves. ‘... We go to class with racist classmates, we go to gym with people who are racists ... It’s part of the experience.’ ”

The ad carried the support of various Duke programs and departments, including the African & African American Studies; Women’s Studies; Latino/a Studies; Latin American and Caribbean Studies.

But the Duke lacrosse case had all been a hoax.

Huge holes in the prosecution’s case would eventually clear the young men, and the court would come down hard on Nifong for misconduct, leading to disbarment and jail.

Both pasts collided in a volleyball game

When BYU and Duke met at the Smith Field House on Friday, one school was freighted with its racist past. The other with a racial hoax. That historic symmetry was about to explode.

It came to light the day after the game. The godmother of one of Duke’s African American players, Lesa Pamplin, tweeted, “My Goddaughter is the only Black starter for Duke’s volleyball team. While playing yesterday, she was called a n— every time she served. She was threatened by a white male that told her to watch her back going to the team bus. A police officer had to be put by their bench.”

Those were the facts delivered not by Duke or BYU, but a close acquaintance to Duke player Rachel Richardson, who had told her of the abuse she endured. It meant that both universities had to scramble to get in front of this rapidly evolving story.

As she broke the news, Pamplin was the first to publicly frame the known facts and express her opinion. In a follow-up tweet she wrote, “Not one freaking adult did anything to protect her.”

On Saturday, BYU Athletics issued a statement: “To say we are extremely disheartened in the actions of a small number of fans in last night’s volleyball match … is not strong enough language. We will not tolerate behavior of this kind. Specifically, the use of a racial slur at any of our athletic events is absolutely unacceptable. We wholeheartedly apologize to Duke University and especially its student athletes.”

Also that day, BYU Athletic Director Tom Holmoe, who had played football for BYU and the San Francisco 49ers, addressed his own fans at another game while visibly angry. ”As children of God, we are responsible. It is our mission to love one another and treat everyone with respect. And that didn’t happen. We fell very short.”

He urged any fans who witnessed the name-calling to come forward. He also told CNN that any BYU student caught yelling slurs could face expulsion.

Duke player says she was 'racially heckled'

On Sunday, Rachel Richardson, put out a statement:

“My fellow African American teammates and I were targeted and racially heckled throughout the entirety of the match. The slurs and comments grew into threats which caused us to feel unsafe. Both the officials and the BYU coaching staff were made aware of the incident during the game, but failed to take the necessary steps to stop the unacceptable behavior and create a safe environment. As a result, my teammates and I had to struggle just to get through the rest of the game.”

There was no reason to disbelieve Richardson. She is an exceptional young woman. Not merely a student-athlete and starter at one of the premier volleyball schools in the country, but one who made the Atlantic Coast Conference Academic Honor Roll. In statements and interviews since, she has demonstrated unusual grace and maturity in a person so young.

BYU officials determined immediately she was credible. The school said in a statement, “When last night’s behavior was initially reported by Duke, there was no individual pointed out. Despite BYU security and event management’s efforts, they were not able to identify a perpetrator of racial slurs.

“It wasn’t until after the game that an individual was identified by Duke who they believed (was) uttering the slurs and exhibiting problematic behaviors. That is the individual who has been banned. We understand that the Duke players’ experience is what matters here. They felt unsafe and hurt, and we were unable to address that during the game in a manner that was sufficient.”

Holmoe told CNN that BYU had reacted during the game when told by the Duke team there was a problem. School officials sent four ushers and a campus police officer into the stands looking for the person who shouted the racial slur.

Who did the heckling? That's not clear

Late Tuesday, the Salt Lake Tribune, which – to its credit – has a reputation for tough coverage of the LDS church and BYU, reported that campus police after reviewing game video do not believe that the man BYU banned from sporting events was the person who yelled racial slurs.

In a statement, BYU Associate Athletic Director Jon McBride said, “Various BYU Athletics employees have been reviewing video from BYUtv and other cameras in the facility that the volleyball team has access to for film review. This has been ongoing since right after the match on Friday night.”

The Tribune reported that a campus officer examining game footage wrote in his report, “There was nothing seen on the game film that led me to believe (that the man) was the person who was making comments to the player who complained about being called the N-word.”

According to The Tribune:

“During the match’s second set, the officer observed, the UVU (Utah Valley University) student was not present when Richardson was serving, which is when Richardson’s family and Duke officials said the slurs were yelled. And later, when she was serving again, he was playing on his phone, the officer wrote.

“But the officers said the athletic department wanted to ban the man, so the school moved forward with that process. The officer told the man not to come to any future games ‘indefinitely,’ according to the report.”

The man, in this case, turned out to be a student of Utah Valley University in neighboring Orem, Utah, The Tribune reported. When police interviewed him “he denied shouting any slurs; he said the only thing he yelled was that the players “shouldn’t hit the ball into the net.”

“He acknowledged that he did approach the Duke player after the match, thinking she was a friend of his who played for BYU (their uniforms are the same color, the officer noted).”

Did her teammates hear the slur?

The facts in this case are undeveloped. Both BYU and Duke have been slow to fill in the blanks. Their statements have been vague as to what happened.

We still don’t have a name or face of the person or persons yelling slurs.

BYU Police Lt. George Besendorfer told The Tribune that no one from the student section or elsewhere at the match has come forward to report the individual responsible for the slur or that they heard it.

I’ve watched the footage of the two times Richardson served from the BYU student section of the court. Both times she shows no reaction that would indicate she was assailed with racist slurs. However, her statement on social media explains that.

“Although the heckling eventually took a mental toll on me, I refused to allow it to stop me from doing what I love to do and what I came to BYU to do; which was to play volleyball. I refused to allow those racist bigots to feel any degree of satisfaction from thinking that the comments had ‘gotten to me.’ So, I pushed through and finished the game.”

One thing you do see on the footage, is that as Richardson serves, several of her Duke teammates are standing behind her, closer to the student section than even she is. Did any of them hear the racial taunts?

At 2:00:24 of the video, Duke player, Sydney Tomlak, No. 4, appears to react to something in the crowd or to be scanning looking for a racist heckler.

Did she or any of the other Duke or BYU players or coaches see or hear a person yelling racist slurs? We don’t know yet.

Media, academia drew broad conclusions

But that hasn’t stopped media, academic and political commentators from drawing broad conclusions about BYU and Duke.

“Every alleged adult in the arena Friday night failed Rachel Richardson and her Black teammates. Every single one,” wrote Yahoo Sports columnist Shalise Manza Young. “The BYU staff did nothing. Perhaps worst of all, Duke’s coaches seemingly did nothing to protect their own players from harm.”

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox tweeted, “I’m disgusted that this behavior is happening and deeply saddened if others didn’t step up to stop it. As a society we have to do more to create an atmosphere where racist a--holes like this never feel comfortable attacking others.”

Renitta Shannon, member of the Georgia House of Representatives, reacted this way:

“BYU is a Mormon university, and if you know anything about the Mormon religion, it’s public knowledge that there’s a whisper campaign that anyone with darker skin is inherently evil and pretty much has no shot of going to heaven.”

If that’s true, she’ll need to square that with headlines like these from NBC News: “The Future of the Mormon Church? It’s Latino”.

Also, roughly 6% of the 16 million members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are Black, reports the Los Angeles Times.

The Michael Irvine rule will reveal the truth

On the flip side, former ESPN commentator Jason Whitlock called the allegations “B.S.” and said, “I find it hard to believe that in 2022 on a religious college campus that someone is shouting the N-word for two hours and no one reacts. No one does anything.”

Right now, there aren’t enough facts to know.

If only one person heard the slurs that will be highly suspect. If several heard the slurs it will be an indictment of BYU students who did nothing to stop it.

America has a long history of racism and a long history of racial hoaxes. Two schools that represent both collided last Friday.

Eventually we’ll know with some confidence what this was.

And all because of the Michael Irvin rule.

“This is a gym. It’s not a football field,” Irvin told an ESPN audience. “On a football field someone may be saying something over here you may not hear. In a gym, everybody hears what is being said.”

Phil Boas is an editorial columnist. Email him at phil.boas@arizonarepublic.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Is BYU racist? How a Duke volleyball game reignited this debate