How this BYU runner’s Olympic aspirations were dashed by a mysterious illness

Easton Allred, once one of the most promising — and star-crossed — young runners in the country, is finished with running at the age of 21, or so he tells himself. In the next sentence, he says, “I’ll never stop hoping.” His relatively brief running career consisted of stops and starts, from high school to college, and even while coping with a strange and insidious illness, he ran brilliantly when he wasn’t flying to Europe to meet with doctors or undergoing surgery or dealing with unrelenting nausea.

“We have come to the point where I don’t ask anymore about how he feels. I know he doesn’t feel great. We’re going to keep fighting. — Lori Allred, mother of former BYU runner Easton Allred

Because of health issues, Allred has run remarkably few races the past five years — since his sophomore year in high school — and he hasn’t run a single race since the end of his freshman season at BYU in May 2021.

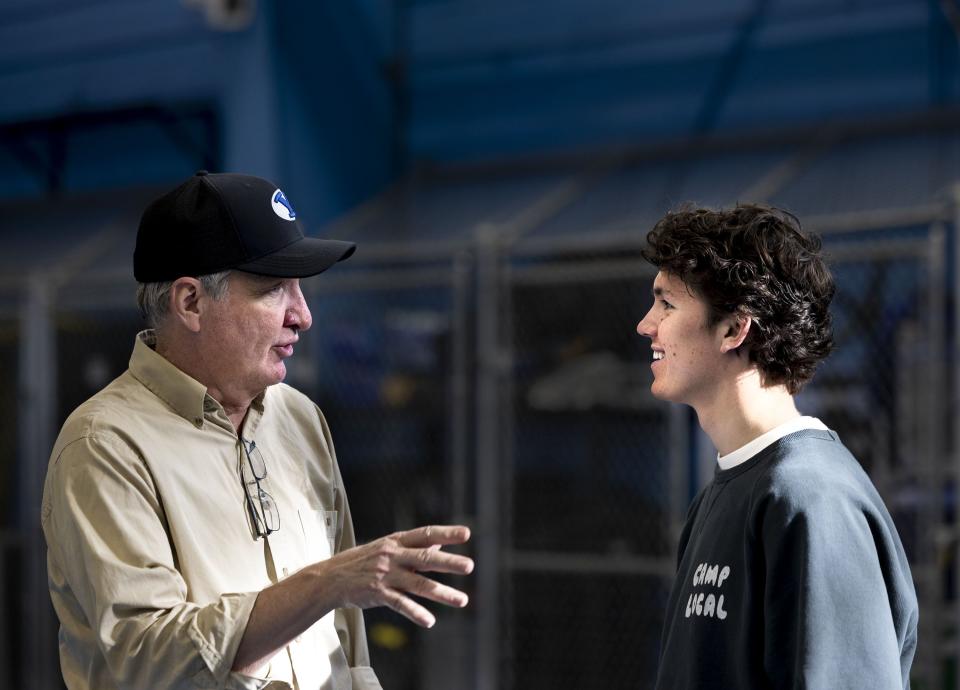

Like Allred, Ed Eyestone, the BYU track and field coach and former Olympic distance runner, can’t help but wonder what might have been. He concedes that Allred’s running career is behind him, but then adds, “There’s still a part of me that thinks, oh, if we could only get that fixed.”

Eyestone was tantalized by the potential Allred showed in his brief time at BYU. Allred would run a strong race, disappear for a time to deal with his illness and then pop up on the running scene again weeks later with another strong performance, only to disappear again.

The last time anyone heard from him he ran a 4:04.49 mile at altitude in Provo — the equivalent of a 4-flat mile at sea level — and a 13:45.54 at 5,000 meters in the West Coast Relays, believed to be the fastest time ever for a true freshman at BYU, which has a rich distance-running tradition. When he ran those times, much of his training had to be done on a zero-gravity treadmill because of his condition.

Allred was raised in Colorado, the only boy among the family’s five children. Darin, Easton’s dad, is a pilot/orthopedic surgeon who flies his own plane to rural areas in the West to perform surgery. His mother Lori, who describes herself as a full-time mom, also owns businesses in Colorado. Allred was a devoted basketball player in junior high and played for an inner-city team. He had no inkling that he had a knack for running until his coach required a weekly individual two-mile run from each player in the offseason.

“The first time I sent in my time I looked at what the other times were and mine wasn’t even close,” he says. “I thought my time must be wrong, so I added a minute. No one believed it, so next time I added two minutes.”

Related

His high school basketball coach wouldn’t let him run cross-country as a freshman, but he did compete for the track team in the spring and recorded times of 4:27 and 9:40 in the mile and two-mile at an elevation of 6,000 feet. His basketball coach relented, and Allred competed in cross-country, track and basketball the following year, and then it became clear that he was a running prodigy. He placed 22nd in the prestigious Nike Cross Nationals, and in the spring he was the fastest sophomore miler in the nation with a time of 4:09.49.

He quit basketball.

It seemed like the beginning of great things for Allred, but soon afterward his health went into decline.

“It was the last time I was completely healthy,” he says.

No one would know it for two more years, but he was suffering from a variety of syndromes that severely compromised his health.

In the fall of his junior year, he thought he had a chronic case of flu. He was fatigued and experienced almost constant nausea, which often resulted in dry heaves. He was sick but still managed to train and race, but he had to stop running for two weeks at the end of the cross-country season. Despite the symptoms and the training break, he placed fifth at the 2018 Nike Cross Nationals in California with a fine time of 15:05.2 on a hilly 5,000-meter course in one of the nation’s two premier cross-country races.

The perfect storm

He moved with his family to Draper, Utah, in December 2018, just in time to prepare for the track season. He continued to get sicker. “I didn’t know what it was, but I knew it was kicking my butt,” he said. He missed the entire track season after undergoing surgery for IT band syndrome.

“He was sick right when he came here,” says Corner Canyon coach Devin Moody. “There were a lot of symptoms. … He just wasn’t getting better. He took a month off. He injured his back playing basketball. It wasn’t until February we got him running again. Then he got the IT band injury. It was a perfect storm of events for him.”

The storm continued. Despite the lost season, he was invited to the Nike Elite Camp, a gathering of the nation’s top 10 distance runners in Oregon for a week of intense training and coaching. It was probably too much too soon after running so little; Allred came home with a stress fracture in his foot. He missed most of his senior cross-country season. He couldn’t begin training until the last two weeks of the season and still managed to place fifth in the state championships and 38th at Nike Cross Nationals.

He was running well that winter and prepared to compete in the New Balance indoor national meet in Boston, but the night before his scheduled flight to the East Coast the meet was canceled because of the pandemic.

Most of the outdoor season was canceled as well. Desperate for races, a handful of top distance runners in the state arranged a 3,200-meter time trial at Taylorsville High. Allred clocked a personal-record time of 8:58. Similarly, in May several of the nation’s top milers arranged a race in California.

Officials at Milesplit, a high school running network, caught wind of it. They set up a timing system and put out the word. A small group of fans gathered to watch the event. Leo Daschbach won the race, becoming the 11th high school athlete to break four minutes in the mile, with a time of 3:59.54. Allred was fourth in a personal-record 4:05.67.

His symptoms weren’t abating. Allred was still intensely nauseated and anxious. He suffered what he calls “brain fog” — forgetfulness, confusion, etc. He didn’t know it, but his parasympathetic nervous system was in disarray. He was, in his words, “incredibly anxious all the time. Essentially my body was just constantly in fight or flight mode. It was like a big adrenaline kick all the time. As if I’m being attacked by something. I alway felt like that. And I was super nauseous.”

Related

The Allreds had spent years looking for answers and their search would eventually take them to Germany (twice), Maryland and Texas to meet with specialists. Doctors initially diagnosed him with general anxiety disorder and treated it with medication, but there was no change.

Moody, his high school coach, recalls, “Doctors were telling him it was in his mind. It led down the wrong path. He felt like it wasn’t controllable, but they were telling him he could control it. They were telling him not to focus on it. The nausea continued. You’d have to pry it out of him, but he’d throw up many, many times, even in school.”

“I can’t even describe how bad the nausea was,” says Allred. “For me, that’s where the anxiety was.”

“We probably went to 30 doctors,” says Allred’s mother, Lori. “I was talking to my husband one night, and I said, ‘Something is wrong with his body.’ He said, ‘When are you going to accept that he has anxiety disorder?’ I said, ‘Never.’”

Syndromes, surgeries and Germany

Two months later her son was diagnosed with Nutcracker syndrome, one of a variety of syndromes that fall under the broad umbrella of vascular depression syndrome, which is defined this way by the University of Maryland Medical System: “… a group of conditions that occur when a person’s blood vessels are under abnormal pressure, limiting the size of the blood vessel and the amount of blood that flows through it.” Nutcracker syndrome occurs as a result of the compression of the renal vein that emerges from the kidney.

Through his own research, Darin found a doctor in Germany who specialized in this field, and he and his son flew there for a consultation. He was diagnosed with two other syndromes — Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) and May-Thurner syndrome. The former causes the compression of an arterial ligament in the diaphragm (which plays a major role in breathing), and the latter is a compression of the iliac vein, a major blood vessel that circulates blood through the hips into the legs.

This family of syndromes causes a wide variety of symptoms that vary from case to case. As a result, it is often misdiagnosed for years, as was the case for Allred.

No one is certain of the cause. “It can be brought on by a virus or an injury,” says Lori, who thinks she knows the origins of it for her son. During his junior year in high school, Easton competed in a Division I collegiate cross-country race. He won by 12 seconds, but there was a price to pay.

“The next day he didn’t feel good,” says Lori. “He hasn’t felt good since then.”

In August 2020, just as he was preparing for his freshman year at BYU, he underwent surgery in Salt Lake City to treat MALS-related issues. The procedure is called a median arcuate ligament release — to put it simply, the surgeon created more space between the diaphragm and the heart.

Nine days later, Allred was running again and was soon churning out 50-mile weeks, much to the surprise of his surgeon. Because the pandemic postponed the cross-country season until February 2021, he was able to run three cross-country races, but his symptoms persisted. He ran five races on the track in the spring, but, as he suspected, his racing days were nearing an end by May 2020.

“I was getting sick again and knew I had to get another surgery,” he says. After racing in the NCAA West Preliminary Round and beating an old high school rival for the first time, he teased his rival, “If I get jacked up again for surgery, I beat you on the last one.” He hasn’t raced since then. His college career consisted of eight races — three in cross-country, five in track.

Two months later, on July 7, 2021, he flew to Texas to undergo a second surgery to place an external stent on the renal vein (which comes out of the kidney) to prevent it from collapsing. Doctors hoped this would relieve the constant nausea (a symptom of the Nutcracker syndrome).

The procedure didn’t merely fail; it made matters worse. Since then, he can’t remain in a standing position for more than a few minutes at a time without experiencing intense pain in various parts of his body. He suffers from chronic headaches, increased back pain, heat flashes and “wonky” (his word) emotions.

He and his father flew to Germany again for an ultrasound diagnosis. Doctors there determined that the stent was causing another compression on the renal vein. On Jan. 22, 2022, he underwent a third major surgery, again in Salt Lake City, to remove the stent and the kidney, which the surgeon transplanted in his pelvis. During the procedure, the surgeon accidentally poked a hole in the aorta, creating a life-threatening situation and further complicating an already complicated situation.

What was supposed to be a two-hour laparoscopic procedure, turned into a nine-hour marathon and a large incision. “He almost died,” says Lori. Moved to a new location, the kidney was functioning when the incision was closed — but then it stopped working. Allred returned to surgery. The surgeon moved the kidney again to a new location in his pelvis and function was restored.

Where does he go from here

A few months later, after a long recovery from surgery, Allred resumed training and ran with the BYU team for five days, and then his body crashed again. He flew to Baltimore to undergo his fourth major surgery (five if you count the redo for the third surgery), this time to place an internal stent on the iliac vein, one of two major blood vessels that break off from the abdominal aorta in the pelvis to supply blood to the lower body. This was to prevent the compression of the iliac vein, which is what had been causing leg and back pain, as well as nausea.

As if he didn’t have enough challenges, three months ago Allred was diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), in which a greatly reduced volume of blood returns to the heart when a person stands up.

Recently, he also underwent a stem cell transplant, using the blood of a donated placenta, which is believed to be the purest form of blood, hoping it will promote healing anywhere in his body where it is needed.

The upshot of all this: The symptoms persist — hot flashes, nausea, headaches, neck pain, lightheadedness, the inability to stand for more than a few minutes — although he says the brain fog, which made school and social life difficult, is gone. He takes many medications, but says, “I don’t see anything changing for a while. I’m just hoping my body heals over time. There’s not a great solution at this point.”

“We have come to the point where I don’t ask anymore about how he feels,” says Lori. “I know he doesn’t feel great. We’re going to keep fighting. I just feel like someday he’s going to be well. He’s only 14 months after a kidney transplant. That recovery can take a year to a year and a half. And he just had the stem cell transplant. We’re just at the point now where there’s nothing left to do.”

Despite all the discomfort and suffering, Lori notes, “Most people who know him don’t know anything is wrong with him. He hides it.”

‘So much more than a runner’

So his once-promising running career is behind him, and clearly he misses it. Last August Allred posted this on Instagram: “You ever just felt called to do something? I’ve thought so many times that one of my main purposes in life is to create impact through running. There is nothing like it. You get to push your limits, be with the best people, and compete like nothing else matters. It’s been so weird to not be able to do what I feel almost spiritually inclined to do. I miss it like crazy ….”

“All competitive athletes have to see themselves as being successful. But, yeah, I was shooting for the moon. I wanted to win the NCAAs. I wanted to go to the Olympics. I kind of thought those things were reasonably attainable.” — Easton Allred

Allred, who is studying advertising and entrepreneurship at BYU, will graduate in a year, but has already launched a career. “It took me a while to figure out what I was passionate about,” he says. He is currently working as a freelance cinematographer. He also will soon launch a business called “TALKED,” which he describes as a “platform for people to connect with people who inspire them. For instance if you want to know how to run faster from (national champion) Courtney Wayment, we can schedule you 15 minutes to talk with her. I am making a lot of connections in the running world and elsewhere — bands, singers, athletes.”

Eyestone notes, “Everyone thinks he’s just such a great young man. Easton is so much more than just being a runner. He’s brilliant. He has a lot going for him.”

Allred wrote and self-published a book when he was 16 and has, at times, maintained a YouTube channel and a podcast. “Fueled for Teens” is a self-help book for teens written by a teen. Says Lori, “It’s tips for teens about setting goals. It’s a good book — a book he needed himself to get through what he’s gone through.”

Asked about his competitive running days and what might have been, Allred says, “I’m a little cautious to talk about that because it’s easy for anybody who’s not running anymore to say he could’ve done better. And all competitive athletes have to see themselves as being successful. But, yeah, I was shooting for the moon. I wanted to win the NCAAs. I wanted to go to the Olympics. I kind of thought those things were reasonably attainable.”

His performances, especially when his limited training is considered, speak for themselves — especially the altitude 4:04 mile and the sea-level 13:45 for the 5,000 as a freshman. Eyestone says, “He just had the ability to hang with paces. He was very competitive, had a great attitude and was happy to take on challenges.”

After not running for more than a year, Allred went to a track last fall and timed himself on a mile run. He finished in 4 minutes, 46 seconds.

“He’d give anything to be able to run, but he’s happy,” says Lori. “He’s had to find other sources for happiness and joy, and I’m proud of the way he’s handled it.”