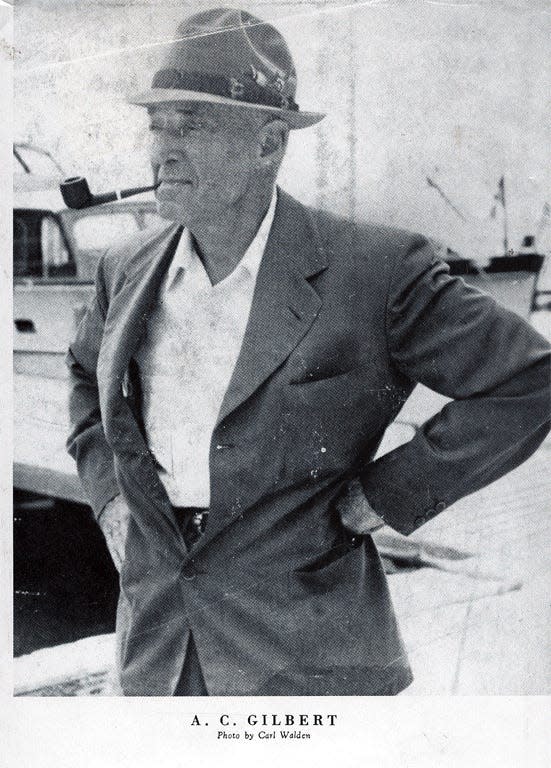

A.C. Gilbert, famous for Olympic gold medal and Erector Set, also saved Christmas

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A.C. Gilbert is a legend in these parts, born and raised in Salem, where he developed a passion for competition and innovation and launched his first business enterprise.

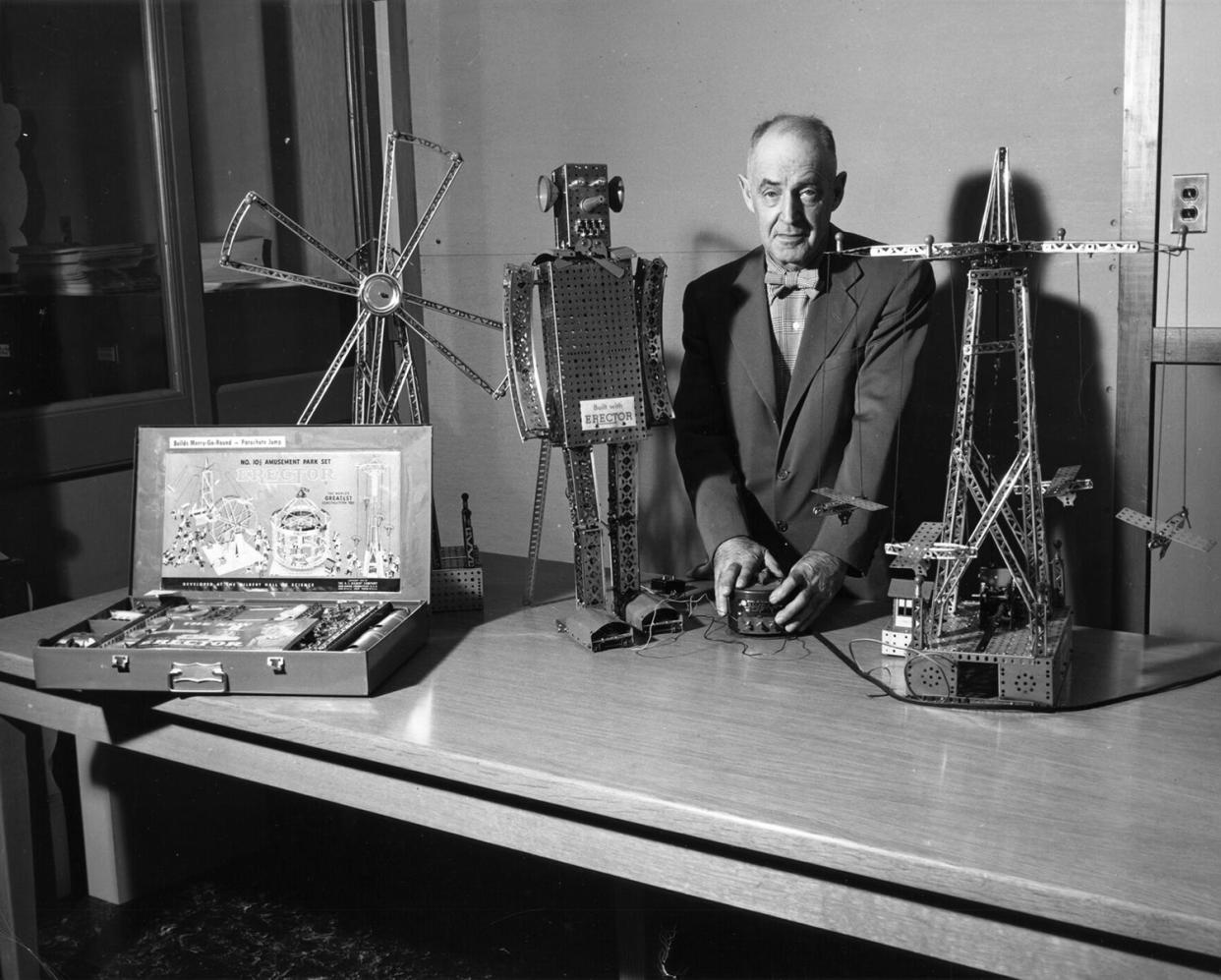

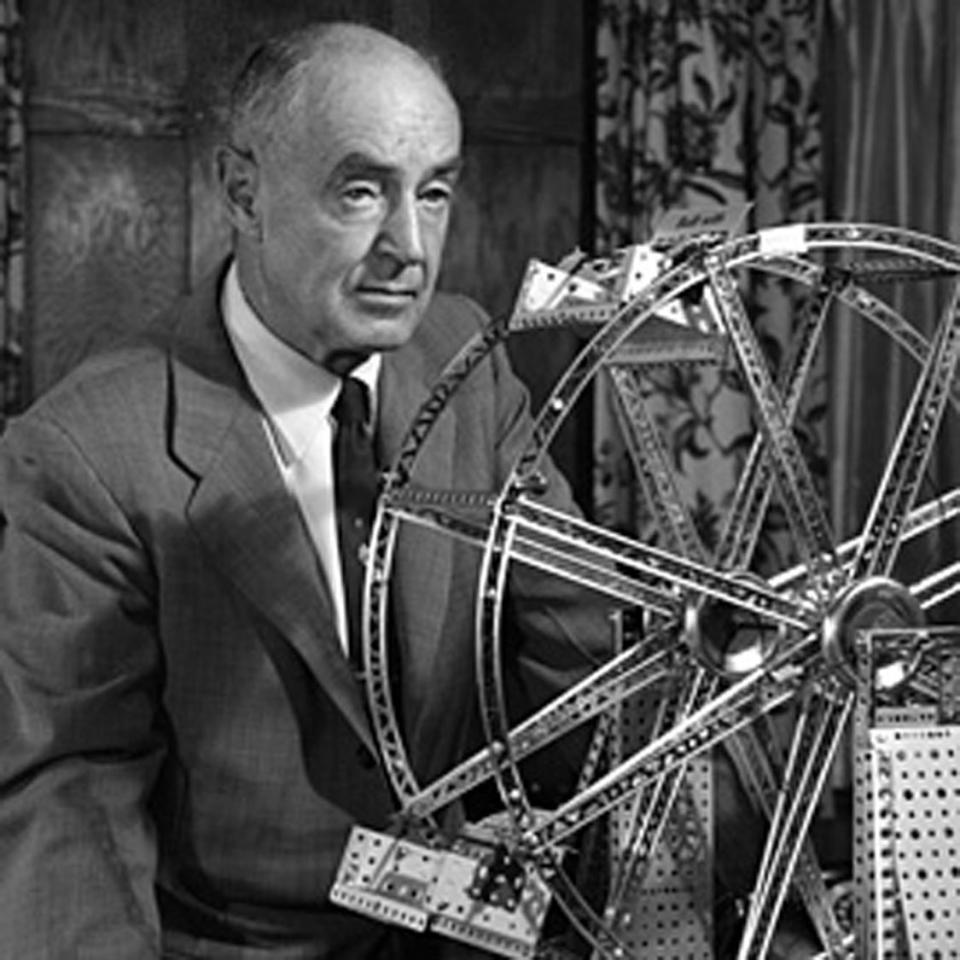

He is most famous for winning an Olympic gold medal in 1908 and inventing the Erector Set five years later.

In between those monumental moments, Gilbert graduated from Yale University with a degree in medicine and passed on becoming a doctor to manufacture magic tricks and educational toys.

His company grew so rapidly in the early years, banks advised caution. By the 1950s, it had annual sales of $20 million, the equivalent of more than $220 million today.

Gilbertwas as much an inventor as an entrepreneur. When he died in 1961, he held more than 150 patents.

As far as Salem natives go, he may be more accomplished than any.

But do you know about his heroics during World War I?

Secret weapon: A satchel full of toys

Gilbert was not deployed overseas and never served in the military. His battle took place on the home front against the Council of National Defense, formed to coordinate resources and industry in support of the war effort.

The council, comprised of some of President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet, threatened to ban toy production and place an embargo on buying and selling Christmas gifts.

Gilbert, on behalf of the Toy Manufacturers of America, was asked to make a presentation at a hearing in Washington, D.C., before the council in the private office of the Secretary of the Navy.

He and his entourage brought along a satchel full of the best educational and most popular toys, which guards at the entrance to the Navy building had to search.

Gilbert had given much thought and careful planning to his presentation, with just 15 minutes to convince the U.S. government not to cancel Christmas. He was up to the task because he believed in the importance of toys.

“The greatest influence in the life of a boy are his toys,” he told the council. “A boy wants fun, not education. Yet through the kind of toys American toy manufacturers are turning out, he gets both.”

Gilbert watched the attitude of the council change as he pleaded his case, with a premise of how children needed toys because the nation needed scientists and engineers.

He was able to close the deal once the toys were unpacked. Imagine the twinkle in his eyes as he watched cabinet members playing on the floor with toy submarines and steam engines, so absorbed the 15-minute time limit was forgotten.

The Boston Post recounted the hearing in an article published Oct. 25, 1918, labeling Gilbert as “The Man Who Saved Christmas.”

The article quoted him as saying: “I didn’t do it. The toys did it.”

He reiterated that years later in his autobiography.

“This hearing turned out to be one of the happiest and most successful undertakings I ever participated in,” Gilbert wrote. “I had a real story to tell, and I had the toys to prove my point.”

His story began on the other side of the country, in the state capital of Oregon.

First business venture: Trapping squirrels in Salem

Alfred Carlton Gilbert was born on Feb. 15, 1884, in Salem. The city had an estimated population of 2,500, the size of present-day Turner.

His parents were Frank and Charlotte Gilbert. They lived in a home at the corner of Cottage and Marion streets NE, according to the Statesman Journal archives. His father was a banker.

A.C. Gilbert demonstrated his resourcefulness and business instinct at a young age.

He spent a summer trapping squirrels when he was about 7. The state offered a bounty of 3 cents a skin because of the damage the rodents were doing. By the end of the summer, he had collected more than 500 skins. When he cashed in, he received $16.26.

“It seemed wonderful to have so much fun and at the same time make money, an idea which must have made a deep impression, because I have never worked at anything to make money unless it was fun, too,” Gilbert wrote in his autobiography.

When he was around that same age, he saw magician Herrmann the Great perform in Salem.

Gilbert was called up from the audience to assist on stage, a favor to his father, who was friends with the hotel manager where the magician was staying. Gilbert wound up impressing Herrmann with his card tricks and getting invited backstage, learning from the pro himself.

Performing magic shows would later help Gilbert pay for his Yale education.

Road to Olympics: Stardom begins at Pacific University

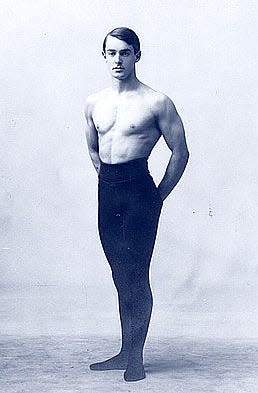

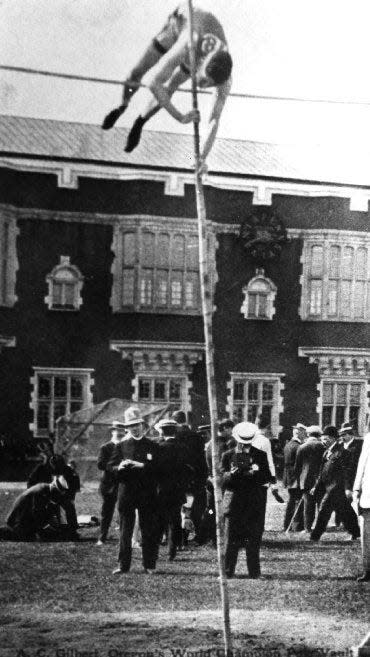

Gilbert was just as passionate about sports as he was about magic, and he was a fierce competitor. He remembered tackling a tricycle race with the same gusto as he did the Olympic pole vault competition.

Reports of him being a frail boy were what Gilbert called a fable.

“No sick or weak boy could have done all the things I did,” he wrote in his 1954 autobiography, "The Man Who Lives in Paradise."

When he was about 10, his family moved to Moscow, Idaho, where they lived on a farm. He had a gymnasium in the barn with a punching bag, a horizontal bar, an old mattress for a tumbling mat, homemade flying rings, a flying trapeze, weights, and a boxing and wrestling ring.

Gilbert grew to 5-foot-7, wiry and strong, and became a star athlete. He went to Pacific University, competing in football, wrestling, track and field, gymnastics and boxing. He organized the track team, helped raise money to build a grandstand, then won most of the events. He led Pacific to the 1903 state collegiate track championship, earning most of the team's points in sprints and pole vault.

After transferring to Yale, where he won an intercollegiate wrestling championship, Gilbert set the world record in the pole vault and later won the gold medal at the 1908 Olympics in London. He shared first place with another American. There was no jump-off, and it remains the only tie for gold in Olympic pole vault history.

Gilbert wrote in his book that his medal was stolen soon after he returned to the United States. A great-granddaughter told the Statesman Journal there is some dispute over whether it was lost or stolen.

“I’ve heard it may have been stolen for the gold and may have gotten melted down,” said Melissa Marsted of Park City, Utah. “It may not even exist.”

Raising the bar: An inspiration for Gilbert descendants

Marsted said her great-grandfather was an inspiration throughout her life, especially in academics and athletics, even though he died four years before she was born. She was a runner, went to Harvard and participated in the U.S. Olympic Trials.

The metaphor "raising the bar" took on importance while she was raising her two sons, a reference to Gilbert's pole vault success.

“I really do feel that he has been a part of our life and an inspiration,” Marsted said.

Her grandmother was Lucretia Gilbert, the middle child of A.C. Gilbert and his wife, Mary. She was Granny Lu to the family and once owned a toy store in Connecticut.

The legacy of Marsted's grandmother and great-grandfather motivated her to start her own company, Lucky Penny Publications, a creator and publisher of children's books. Its Silver Dollar Press division, featuring autobiographies, memoirs and other non-fiction titles, reissued her grandfather's autobiography as an eBook.

Thinking big: Steel towers on commute spark invention

Gilbert's autobiography starts with his childhood, with the first chapter titled "Salem Magic." The 27-chapter book covers all the milestones of his athletic and business careers, none more life-changing than the invention of the Erector Set.

He co-founded the Mysto Manufacturing Company just before graduating from Yale in 1909 to produce and sell magic sets. The company eventually expanded to toys, including what Gilbert originally called the Mysto Erector.

The inspiration came while riding a commuter train from Connecticut to New York, where the company opened a store in 1910. Gilbert watched out the window as railroad crews worked to convert steam to electricity. The architecture of the steel towers erected to carry the power lines especially fascinated him.

He described in his book how one day in the Fall of 1911, he went home and used cardboard to cut out girders of several different lengths and shapes. He had a machinist at the shop make a set out of steel, then got a box of bolts and nuts and started putting pieces together.

Gilbert worked on perfecting the Erector for more than a year before introducing it at toy fairs in 1913. The toy drew crowds, and some of the biggest buyers in the business placed orders.

With the toy came a new type of advertising, with a personal message from Gilbert. Almost every ad carried a headline that remained Erector’s slogan for years: “Hello, Boys! Make Lots of Toys!”

Gilbert was known to pump profits back into the business. The company opened a sales office in New York in 1914, one in Chicago the following year and a new factory in Connecticut the next.

He called 1916 one of the most eventful and successful years in the history of the business.

“We went over a million dollars for the first time,” he wrote in his book, “brought out several new products, introduced new promotion methods, bought a new plant, changed our name.”

Household name: Every parent knew who A.C. Gilbert was

The toy business was booming by the time the U.S. entered the war, which slowed growth for the A.C. Gilbert Company.

The company’s main plant was turned over to war work for most of 1918, making parts for machine guns, gas masks and Colt .45 automatics under subcontract from Winchester.

“And we had a good record, proving that we could turn out top quality precision goods, although some people had doubted that a toy manufacturer could do it,” Gilbert wrote in his book.

The company continued to produce small quantities of established toys and even introduced a few new items. And then, Gilbert saved Christmas.

“I hope that he becomes better known for not just the unique person he was but for his belief that toys matter,” said Bruce Watson, whose biography of Gilbert, “The Man Who Changed How Boys and Toys Were Made,” was published in 2002. “It really does matter what you give your kids for Christmas. Just as he did with the bureaucrats who got down and played on the floor, he convinced parents toys matter.”

Watson’s book highlights the influence of Gilbert’s toys in helping boys and some girls choose careers as engineers and scientists.

The company branched out to include chemistry and microscope sets in subsequent years, even a nuclear science kit containing a small sample of radioactive material.

“Toymakers don’t become household names very often, then or now,” Watson said. “He was truly a household name. Every parent knew who A.C. Gilbert was. He was the father of the educational toy industry.”

On the screen: TV movie takes liberties with Gilbert's story

A television movie called “The Man Who Saved Christmas” was broadcast on CBS the same year Watson’s book came out, with no connection. Like most Hollywood adaptations, several historical liberties were taken. The most egregious was omitting Gilbert’s two daughters and featuring a son not yet born.

“My aunts felt left out of the whole thing,” said David Gilbert, a grandson of A.C. Gilbert. “But it did certainly popularize the whole story.”

When A.C. Gilbert retired in 1954, David’s father, A.C. Gilbert Jr., took over the company. David was too young to know his grandfather well before he died.

“He was larger than life,” said David Gilbert, who lives in Virginia. “I think our family treated him that way, so there wasn’t a warm connection. He was reserved around his grandchildren.”

What he remembers most were his stuffed big-game trophies, which filled cabins in Connecticut and at White Swan Lake in British Columbia.

A.C. Gilbert was an avid hunter his entire life. One of his first hunting trips was as a youngster in the Cascade Mountains, and he got his first buck in Nye Creek near Newport. Once retired, he had more time to travel and hunt, bagging trophies from Alaska to Canada.

Remarkable resume: But still just a kid at heart

Today, David Gilbert is involved with the A.C. Gilbert Heritage Society, a nonprofit based in Ohio. It was established in 1991 to showcase and celebrate the company’s educational toys. He said its 400-plus members are primarily Erector collectors, and the society holds an annual conference.

His grandfather’s legacy is preserved by the society and museums from Oregon to Connecticut.

The Gilbert House Children’s Museum opened in 1989 in Salem, dedicated to the spirit of the man who believed children could learn while playing with toys. The Eli Whitney Museum in Hamden has featured a series of exhibitions since 1991 celebrating Gilbert’s toys and his career.

While revolutionizing the toy industry, Gilbert also helped modernize other aspects of life as a by-product. For example, he invented enamel wire for winding electric motors, and a Yale student used an Erector Set to make a model of the first artificial heart pump.

Gilbert lived a remarkable life as a professional magician, Olympic athlete, inventor, toy millionaire and much more. Most of all, he was a kid at heart.

A few years before he retired, Gilbert reflected on his career in a 1952 article in The New Yorker.

“I guess my life hasn’t been anything to set the world on fire,” he told the magazine, “but it’s been interesting, and I know this: I’ve had more fun than the average boy.”

Capi Lynn is a senior reporter at the Statesman Journal. Send comments, questions and tips to her at clynn@StatesmanJournal.com. Follow her on Twitter @CapiLynn and Facebook @CapiLynnSJ.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Olympian, Erector Set inventor A.C. Gilbert saved Christmas