Before César Chávez, this Mexican woman was one of the most powerful people in US politics

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas – Dr. Clotilde Pérez García swept into the elementary school where voters were gathered to elect a new state representative. The voting precinct chairman emerged to greet her. Voters stopped to hug her. Women called her “comadre,” a Spanish term for someone as close as family.

They all knew the doctor, who had delivered most of the babies in the voting precinct. And they all knew who she was voting for – and who she wanted them to vote for – Al González, a local business owner and former amateur boxer.

As a crowd gathered to chatter and laugh with García, a poll worker employed by a rival candidate rushed to the phone. It was 1966. In Corpus Christi, a city that sits along the southern curve of the Texas Gulf Coast, García was not to be challenged.

“Please, I need to be relieved from duty,” the worker told the campaign headquarters. The election was over, they should give up, he said, la doctora had made her choice.

For decades, García was one of the most influential people in the United States. García shaped politics and policy for Latino communities during the Chicano civil rights movement, was one of a few Mexican American women in the medical profession in Texas and was recognized for preserving Mexican American history nearly erased under the weight of time and racism.

Her achievements remain almost as uncommon now as they were then: In 2019, less than 4% of doctors identified as Hispanic, Latino or of Spanish origin, and of those, less than half were Hispanic women. Latinas also remain largely underrepresented in politics despite the community’s growing population in swing states such as Florida, Ohio and Wisconsin. And efforts to require the teaching of Chicano history in U.S. public schools remain divisive.

This series explores the unseen, unheard, lost and forgotten stories of America’s people of color.

But while García is an icon in Corpus Christi, where buildings are named after her and her son and granddaughter remain prominent figures, her story has often been lost outside of South Texas.

Néstor Rodríguez, 79, grew up in Corpus Christi and remembers it as a city divided by social segregation. The city’s Westside was almost completely Mexican American and working class, while whites lived to the east and later moved farther south. Rodríguez is now a professor of sociology with a focus on migration at the University of Texas at Austin.

He remembers hearing García’s voice on the radio, promoting civic involvement. Her medical office was at the corner of his street. Sometimes she stopped by to say hello to his mother or to borrow a comb.

“She had this ability to be close to people and to connect with people. I’m talking about Mexican American people there,” Rodríguez said. “For many institutions, these people were low priority because we were poor people. But for Dr. García, it didn’t seem to matter to her at all.”

Mexican woman overcame racism, sexism to excel in medicine

She was an immigrant from Mexico.

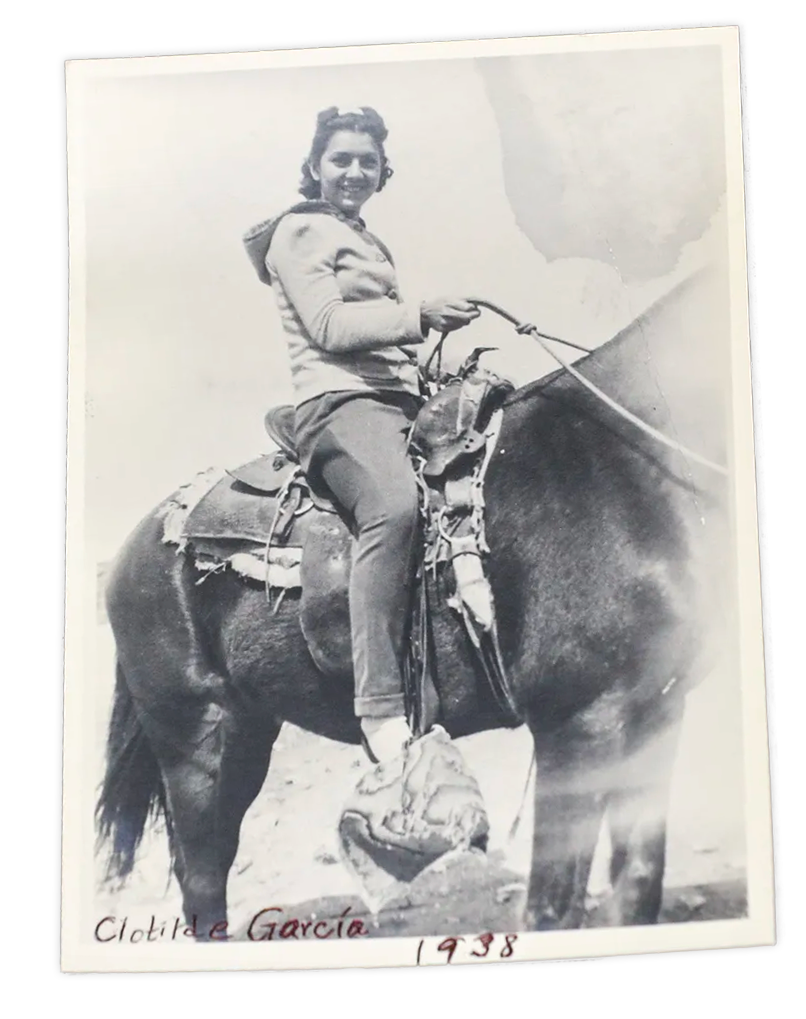

García was born on Jan. 9, 1917, in Ciudad Victoria, a tourist and industrial center that is a four-hour drive from Matamoros on the Mexico-Texas border.

She was the fourth of seven children, and the second of three daughters, born to José García, a college professor, and Faustina Pérez García, a schoolteacher.

She was still an infant when the family moved months later across the border to Mercedes, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley, to escape an attack on their town during the Mexican Revolution.

The U.S.-Mexico border was more porous then, and the family simply crossed from Ciudad Camargo to Rio Grande City, Texas, without any concern for visas or Border Patrol agents, said her son, Tony Canales.

The García patriarch demanded excellence from his children, especially when it came to their education.

“My father encouraged all the family to be physicians because he said it was the only way you could be independent and serve humanity,” García would later recall.

At their father’s urging, six of the seven García siblings earned medical degrees.

For García, the path was not as direct as it was for her brothers, who were favored because of their gender.

She earned an associate degree from a South Texas junior college in 1936 and then a bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin, where she studied pre-med, zoology and chemistry, two years later.

There was not enough money to send her and her brothers to medical school, so while the men finished their degrees, she pivoted to teaching.

Finding a job wasn’t easy because many schools “would not hire Mexicans,” said her son, Tony Canales.

Discrimination against people of Mexican descent grew rampant in Texas after Anglo Americans helped wrestle the state away from Mexico in 1836 and continued for more than a century, according to historical accounts. Mexican Americans accused of helping slaves escape to Mexico were cast out of their homes in Central Texas; they were lynched by white supremacists and law enforcement; they were subject to poll taxes and literacy tests; and they were segregated by residential areas, schools and public facilities. Though Jim Crow laws primarily targeted Black people, Mexican Americans were also bound by the laws on the premise that they were “an inferior and unhygienic people,” according to the Texas State Historical Association.

When she was 23, García became a naturalized citizen. She began teaching in and running schools in South Texas towns.

During World War II, García helped in the war effort by calibrating bombs at a military base in Dalhart, Texas. In 1943, she married Hipólito Canales, a rancher. When they divorced two years later, she left the marriage with a son. Tony Canales was her only child.

García was a single mother in her mid-30s when she enrolled in medical school. She was the only Mexican American woman out of seven women to graduate from the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston in 1954. Although her ethnicity set her apart, she and the other handful of women in the medical program all faced gender discrimination, she would later say.

Staff at the school told the female students, “We do not want women in medicine. You are taking a man’s job. … You are going to get married, and all the money the government has invested in an education is going down the drain,” García recalled.

García refused to be underestimated.

One time, as she rode in an elevator with male classmates, a football player asked her, “What are you doing here in medical school? Don’t you know women’s place is at home, taking care of children and taking care of a husband?”

She gave him a look. “Oh, honey, I didn’t know you cared,” she said. “Are you proposing?”

That shut him down, she later said.

She wouldn’t let it go. After that, to his embarrassment, she would blow kisses at him whenever she saw him on campus.

“These were very difficult times. There were no mentors for her,” her granddaughter, Barbara Canales, said. “Powerful women are an exception even today, but then, they were even more rare. She knew that it made people uncomfortable. So in order for her to galvanize folks to her, she used wit in order to disarm.”

García covered pediatrics, geriatrics, obstetrics, even surgery. In all, she delivered more than 10,000 babies throughout her career. García never took off her medical school ring, her son said.

“We did everything from bones to brains,” Clotilde García said in a 1994 interview with the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, after she’d retired. “There was no distinction.”

Her medical office catered to low-income families.

When she began practicing, García charged $3 for an office visit, a bit less than her competitors who charged the standard $5 rate of the time. For delivering a baby, including pre- and postnatal care, the cost was $25. If a woman could not afford the prenatal tests, García would cover the fees.

“I think the most important part of her career was that here was a doctor that the people could trust and that they could afford,” Barbara Canales said. “It was key for women who were delivering children to have a female be their doctor.

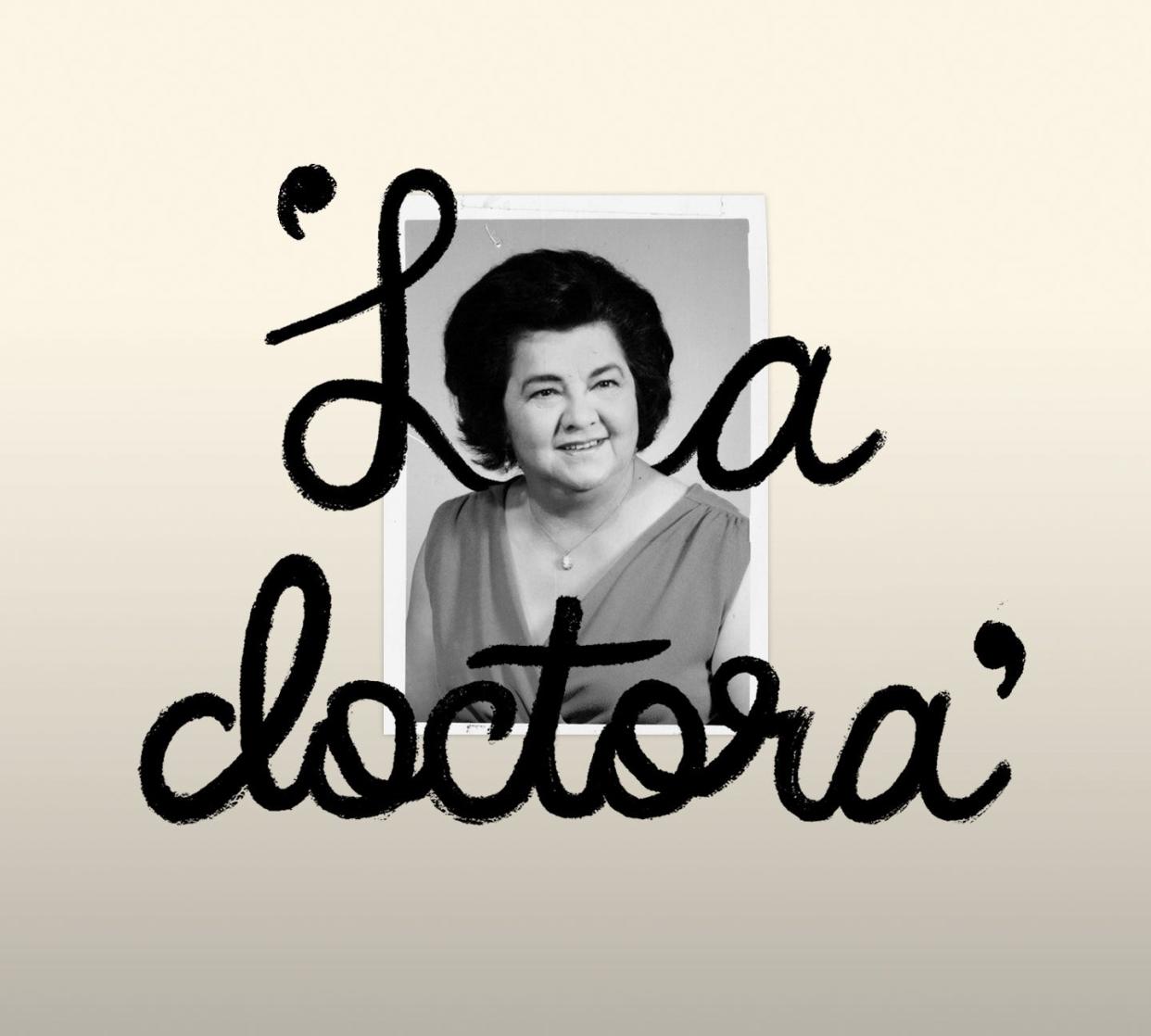

“She was like Madonna of her time because she was known as la doctora – just ‘the doctor,’” her granddaughter added. “You know which female doctor you’re talking about.”

Lawmakers sought endorsements from García family leaders

García loved her family of doctors and supported them. But occasionally they made it challenging for her to define her own identity and passions.

Her oldest brother, Dr. Héctor P. García, often took center stage in a family dedicated to public service. After serving in Europe in World War II, he founded the American GI Forum in 1948 to advocate for military veterans who were denied health care and other benefits promised to them by federal law. Many of the founding members were Mexican American veterans with little formal education who were in need of government aid.

Héctor García and the American GI Forum drew national attention in 1949. A funeral home director in Three Rivers, Texas, denied the use of a chapel for the late Félix Longoria, a Mexican American soldier who had died in combat in the Philippines. It had taken four years for the U.S. Army to return Longoria’s body home, and the veterans group insisted he receive a proper burial.

“The whites won’t like it,” the funeral home director told Longoria’s widow. He said Longoria could only be buried in the cemetery’s “Mexican section.”

Héctor García intervened, sending telegrams and letters to local and state officials, as well as then-Texas Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson arranged to have Longoria buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

The American GI Forum soon began defending the civil rights of Mexican Americans in other areas: voter suppression, lack of representation in juries, police brutality and school segregation.

Héctor García’s younger sister campaigned right beside him.

While he fought in the war and Clotilde García was a teacher, she sent him money and helped pay the family’s bills. Later, she covered his patients while he went on activist trips.

She had her own civic ambitions. García helped organize the Viva Kennedy and Viva Johnson organizations, which aimed to turn out the Mexican American vote for the respective politicians’ presidential bids. She was also active in the League of United Latin American Citizens – known as LULAC – and, in 1966, served as the civil rights organization’s national health director.

In 1966, brother and sister joined the United Farm Workers in a 10,000-strong march that began in Rio Grande City and proceeded to Austin to lobby top state officials, including then-Texas Gov. John Connally, for a higher minimum wage.

By that time, the Garcías had made a name for themselves and were on first-name terms with the governor. Per family lore, Connally met with the marchers and told the siblings: “Cleo, Héctor. Please stop. Please don’t embarrass me.”

They refused.

“They needed each other in order to promote the cause. They were joined at the hip on how to be changemakers,” Barbara Canales said. “They were the first changemakers for Latinos. They predate César Chávez.”

National leaders who wanted to woo Latinos began making stops in South Texas to get the blessings of Héctor and Clotilde García.

When former Vice President Hubert Humphrey visited Texas in 1968 to speak to Connally about being his presidential running mate, Clotilde García and 250 other women cheered Humphrey on outside a hotel in Austin. A member of a radical Mexican American activist group approached the hotel to heckle Connally, and Clotilde García repeatedly whacked the radical on the forehead with her picket sign and told him to go home.

The activist, Carlos Guerra, would go on to become a prominent Texas newspaper columnist. When he reminded Clotilde García about the incident a decade later, she told him, “Oh, I’m sure it was an accident, Carlos. I wouldn’t do anything like that three times.”

That side of her likely came from growing up with four brothers who were all activists and brought her “into the fold as an equal,” Barbara Canales said.

“They did not distinguish male or female,” she said. “I think that contributed to her … feistiness, or her determination, her fortitude. But I think her wit was all her own.”

When she worked at a Corpus Christi hospital alongside her older brother, Héctor García, patients sometimes confused her for a nurse or, worse, her brother’s assistant.

“I made better grades than he did!” her son recalled her saying. “I’m the doctor.”

García family advocated for assimilation

To be sure, some Mexican American political groups, including the American GI Forum, today might be considered conservative and controversial by many Latinos, the vast majority of whom tend to vote for Democrats and support immigration reform.

While the García siblings defended civil rights for Mexican Americans, they downplayed their own immigrant identity, said Rodríguez of the University of Texas at Austin. In an era plagued with racism and McCarthyism, where incoming Mexicans were treated as communists, spies, or simply not as good as Anglo Americans, the American GI Forum initially supported Operation Wetback – a 1954 federal initiative that would go on to apprehend and deport more than 1 million undocumented workers.

The García siblings argued Mexican Americans were “finally having some mobility” in education and jobs, Rodríguez said. The thinking was a “large number of undocumented migrants coming into the country will drag down the accomplishments of the Mexican Americans,” he said.

What the Garcías promoted was assimilation: becoming U.S. citizens, voting, effecting change in education, health care access and infrastructure.

They were also generous with those they cared about. People who knew Clotilde García would later remember her patience and nurturing approach: dropping by a patient’s house to say hello, making house calls to poor neighborhoods and colonias – unincorporated areas with no running water, electricity, or paved roads.

“The community needed voices,” Rodríguez said. “We needed civic leaders like Dr. Cleo García and Dr. Héctor García.”

Politics aside, Clotilde García never forgot her history. In the mid-1970s, she began to research and write articles and books about Spanish colonization in Texas and Hispanic genealogy. One of her areas of interest was land grants in Texas, by which a Spanish royal commission gave plots of land to settlers. She developed an expansive database of families in Texas and the Mexican states of Nuevo León and Tamaulipas connected to the Garza Falcón land grant, one of the largest in South Texas, according to Refusing to Forget, a project organized by professors to study the history of state-sanctioned violence against Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

In 1973, then-Texas Gov. Dolph Briscoe appointed her to a committee to rewrite Texas’ constitution. In 1984, García was one of the first 12 women inducted into the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame. Her work led her to co-found the Spanish American Genealogical Association in 1987. And in the 1990s, she was awarded honors by Pope John Paul II and King Juan Carlos I of Spain for her historical work. Then-Gov. Ann Richards appointed her to the Texas Historical Commission.

“That whole ‘sí, se puede,’” Barbara Canales said, “she embodies it.”

A Mexican American family embraces politics

At 86, Clotilde García died from complications of a stroke and breast cancer in 2003.

Her political involvement indirectly influenced the career of her son, who became a civil rights lawyer.

Tony Canales, who served as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Texas from 1977 to 1980, was a lawyer for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, a national civil rights organization, for more than a decade, Barbara Canales said. He filed litigation for desegregation efforts on behalf of LULAC and the American GI Forum.

His daughter, Barbara Canales, became the top elected official in Nueces County, where Corpus Christi is located, and in recent years helped coordinate testing sites, vaccinations and treatment clinics to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

She hopes her grandmother’s story will be recognized in the coming National Museum of the American Latino, the Smithsonian Institution’s first museum devoted to Hispanic achievement.

The goal, Barbara Canales said, is to “make sure that people know that whatever good things that happened to them in their life, if they have a Spanish surname and they’re from these parts, (García) helped make that life a better one.

“We talk about trailblazers, people who make way for others. She did that.”

More: What LGBTQ, Native American and other civil rights leaders learned from Black protesters

More: WOMEN OF THE CENTURY

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Famous women you should know: This Mexican immigrant ruled US politics