Cal Poly canyon hides a village of curious structures: The Architecture Graveyard

In the northeast corner of Cal Poly’s San Luis Obispo campus, the wind whistles through more than two dozen perplexing structures nestled into a grassy canyon.

The structures have unorthodox designs, with some resembling mushrooms, palm trees or the bones of a pirate ship. All were built by students over the last six decades, and most are covered in graffiti.

Since the early 1960s, Poly Canyon has served as a spot for students to experiment with structure design and construction techniques.

Though some have nicknamed the canyon the Architecture Graveyard, the experimental lab is very much alive, according to Kevin Dong, interim dean of Cal Poly’s College of Architectural and Environmental Design.

“It’s really a beautiful playground and experimental place for students and faculty,” Dong said.

Once a year, the university hosts the Design Village competition in Poly Canyon, challenging students to build temporary structures in which they can live for 48 hours.

In addition, students build permanent structures in Poly Canyon about every other year in projects unrelated to Design Village, Dong said.

“They just want to leave a legacy,” Dong said.

Where did the structures in Poly Canyon come from?

George Hasslein, the founding dean of the College of Architecture and Environmental Design, wanted to create a place for students to build large-scale experimental structures, according to Cal Poly’s website.

When building consultant and retired Cal Poly professor Nick Watry enrolled as an architecture student in 1960, he spent the first week of his freshman year in Poly Canyon.

Back then, architecture students spent the first week of fall quarter cleaning up the canyon — with tasks ranging from clearing vegetation to building benches out of fallen trees, he said.

Architecture students also spent the week of Poly Royal — Cal Poly’s previously named open house celebration — building permanent structures designed by seniors, according to Watry.

“Part of the mystique of the canyon was that we weren’t just engineers, we weren’t just contractors, we weren’t just architects,” Watry said, noting that those factions “in the real world, are often at odds with each other.”

“We did it all together. We were all equal,” he added. “We all so appreciated what the other’s expertise was, and we did magnificent stuff.”

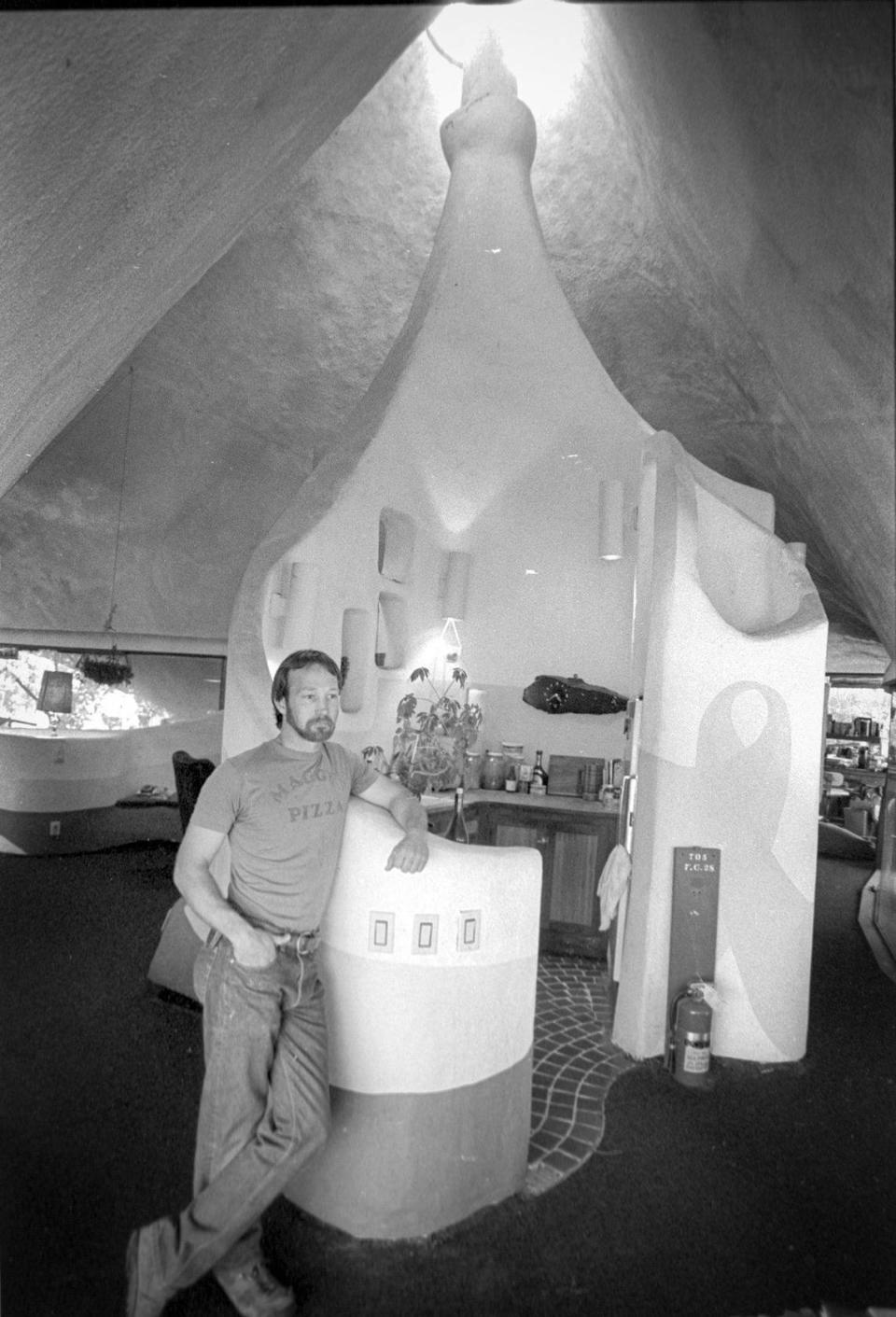

As a sophomore, Watry worked on what is now the oldest standing structure in the Architecture Graveyard: the Shell House, a concrete building with a distinctive cone-shaped roof. The structure originally had a working kitchen and bathroom — rare for structures in the canyon — and occasionally housed guest lecturers.

The 35-foot-tall house used to have doors and large glass windows, which have since been broken.

The school didn’t offer funding for Poly Canyon projects back in the 1960s, so students relied on donations and even stolen materials to complete their structures, Watry said.

According to Watry, there’s a rumor that Hasslein bailed a few students out of jail after they stole 2-by-4 wood boards from a nearby construction site for their project.

When Watry returned to Cal Poly as an architecture professor during the 2000s, he advised a student project dedicated to redesigning the Blade Structure.

The structure, located near the entrance of the canyon, looks like a concrete flower with nine petals.

By 2003, most of the blades had collapsed due to wear and tear, Watry said, as well as cows scratching their backs against the structure.

Watry’s students designed the replacement blades to be more structurally sound, he said, and they still stand.

Watry said facilitating a hands-on learning experience for his students also allowed him to relive his college days.

“(It was like) I was a student again. I was in dirty old clothes hammering stuff,” he said with a chuckle. “The kids are so special. As a teacher, you just set up the situation for them to be engrossed with it to be inspired by it to love it as much as we loved it.”

Craig Park, director of the company Digital Experience Design, studied architecture at Cal Poly during the 1970s. He said Poly Canyon is critical for teaching students how to make their designs a reality.

“It’s all very inspirational for a young student to see that your peers and other students actually constructed infrastructure,” he said.

Caretakers once lived in Architecture Graveyard

For years, a handful of caretakers lived in Poly Canyon.

They were primarily charged with keeping the area “looking tidy,” according to Lucas Hogan, who was a Poly Canyon caretaker when he attended Cal Poly during the early 2000s.

This included removing vegetation around the structures for fire suppression, painting over graffiti, helping students with senior projects in the canyon and acting as a security guard at night, Hogan said.

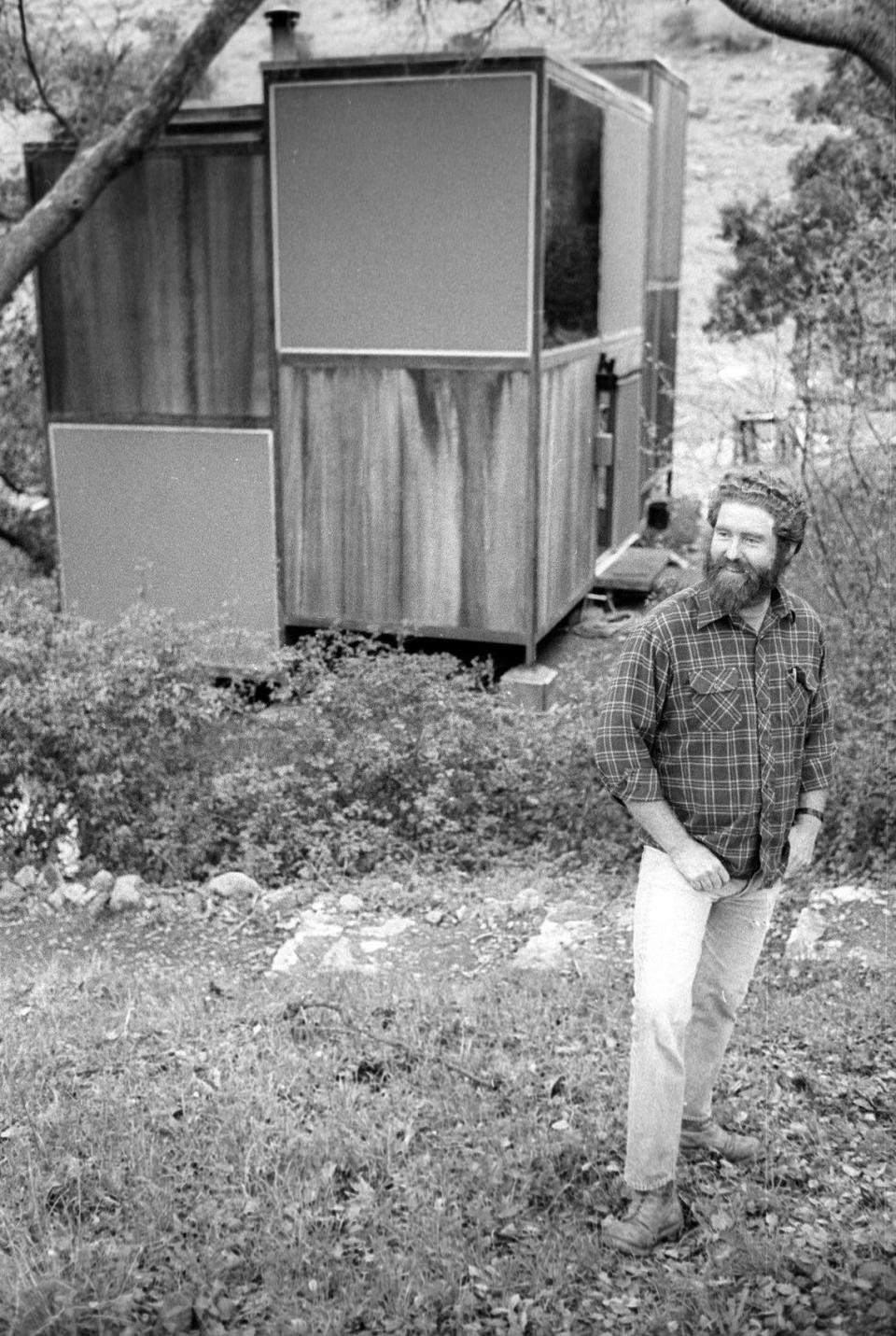

He lived in the Modular House, which was built by students during the late 1960s. Instead of paying rent, Hogan took care of the canyon 10 hours per week.

“A lot of my job was shining a big flashlight on people and saying, like, ‘You gotta go,’ ” Hogan said with a chuckle. “It was mostly just to keep people from graffiti-ing or breaking stuff.”

When Hogan lived in the Modular House, the structure had a living room, a working kitchen and bathroom, and two lofts for sleeping.

There was a shower with running water supplied by a nearby stream, and a septic system to dispose of wastewater. Cal Poly delivered water coolers to the house for drinking and cooking before installing a ultraviolet water filtration system, Hogan said.

The walls were plastered with road signs, although Cal Poly recently tore out those walls to prevent graffiti.

The Modular House had electricity but no internet, Hogan said, so he studied on campus.

After about six months living at the house, Hogan decided he needed a roommate. He came to that realization while chasing around a rodent before a 7 a.m. class.

“I had cornered a rat under the stairs, and I’m in my underwear with a pot in one hand and a tennis racket in the other,” Hogan said. “The rat’s staring up at me, like, ‘What you going to do, man?’ ”

“I thought, ‘I need another human being out here,’ ” Hogan said.

In 2010, Cal Poly student Brian Planas moved into the Modular House with Hogan.

Cal Poly didn’t have a budget for maintenance for Poly Canyon at the time, so the duo used what materials they could find to keep the canyon clean.

In their free time, they hosted bonfires and movie nights, projecting films on a big, blank wall in the living room.

“Living in Poly Canyon is a lot closer to what 12-year-old Lucas thought adulthood should be,” Hogan said. “I’ve always enjoyed those slightly off-beat, slightly quirky places.”

According to Planas, Poly Canyon is shaped like a bowl, which creates excellent acoustics. Sometimes, he would play his electric guitar at the top of the canyon — listening to the music echo across the landscape.

The canyon is far enough away from the city to avoid light pollution, he added, making it a great spot for stargazing and watching meteor showers.

“It was incredible ... just being away from the buzz of things, being out under the stars,” Planas said.

“In the morning, the fog is just lifting over the canyon and you’re like, ‘Wow, I get to live here. This is great,’ ” Hogan added.

When Hogan graduated from Cal Poly, Planas worked alone in the canyon for about a year. Then Planas graduated in 2011, and the university ended the caretaker program.

Cal Poly brought the program to an end because it was too expensive to update the water and electrical systems out in the canyon, according to Dong.

Dong said he would be happy to see the university build a home on the edge of the canyon with its own water and energy system to house a group of students to take care of the structures — though there is no official plan to do this.

Dong leads an annual cleanup effort for Cal Poly students and staff to remove graffiti and vegetation in Poly Canyon. It’s often held before the university’s Open House.

According to Hogan, however, it helps to have folks in the canyon in person.

“If there’s no one occupying (the houses), nature takes them back pretty quick,” Hogan said. “As soon as nature starts taking them back, people come in and start abusing them.”

Students design Poly Canyon project

Cal Poly architectural engineering student Brayden Martinez first visited Poly Canyon after COVID-19 restrictions lifted his sophomore year. He described the spot as “one of the most serene places on campus.”

Martinez and three other architectural engineering seniors are building a structure in Poly Canyon this school year.

The structure will demonstrate the different types of connections for steel moment frames, which hold up buildings during earthquakes, according to Cal Poly architectural engineering student Carsten Huber.

The group designed the structure to deter vandalism, limiting areas that could have graffiti on them and placing it near the Agriculture House, a home in Poly Canyon that houses students and staff who tend to the university’s livestock.

“There’s really not any vertical surfaces to vandalize,” Huber said. “And it’s super easy to paint over.”

Huber and his fellow students started designing the project during spring quarter and plan to finish construction by the end of the school year.

“We’ve all been shoving classes down our throats so that we can have kind of an open senior year to do a group project,” Cal Poly architectural engineering student Jared Schieferle said. “We’re all very excited to just get out there and start building.”

“We’re leaving our mark on Cal Poly,” said another architectural engineering student, Gaspar Solorio.

How can SLO university revitalize the canyon?

In the years since the caretaker program ended, Poly Canyon has fallen into disrepair.

Watry said “risk management” has led to Poly Canyon’s deterioration.

Now, projects require insurance and permits, which he said makes the process more complex and cost prohibitive.

Meanwhile, fewer professors are willing to advise senior projects in Poly Canyon because it’s so time intensive, he said.

Watry co-founded The Alliance, a nonprofit organization that provides grants for interdisciplinary, student-led projects. The organization is especially excited to fund projects in Poly Canyon, he said.

“My wish would be that there would be students living in structures that are restored and made habitable again, to protect the graveyard — if you want to call it that,” Watry said.

Hogan would like to see architecture students build more permanent structures in the canyon, but he also wants other departments to use the space.

The theater department could host performances in the structures, he said, while horticulturists could grow plants in the greenhouse and art students could paint murals over the graffiti.

“It’s a unique space in the world. There are very few universities where you have the ability to, as an undergraduate student, someone in your early 20s, to build a project,” Hogan said. “The Cal Poly ethos of ’Learn by Doing’ is really embodied in that space.”

“The more people with a strong, positive connection to it, the more people will want to keep it nice,” he said.