California Democrats want solitary confinement reform. Why Gavin Newsom may be a roadblock

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom and key lawmakers at the Capitol are struggling to find a consensus over solitary confinement reform, and there are few solutions in sight.

Assemblyman Chris Holden, D-Pasadena, continues to try to win support for Assembly Bill 280, which would restrict the use of solitary confinement in prisons, jails and immigration detention facilities to 15 consecutive days.

His bill would ban this kind of isolation entirely for certain groups, including those who are pregnant, those 60 and older and those 25 and younger.

Another measure, Senate Bill 733 from Sen. Steve Glazer, D-Orinda, would collect data to “track (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) progress toward improving solitary confinement standards,” as well as specific information on inmate demographics and experiences with isolation.

Reform advocates backing significant restrictions on solitary confinement fear Glazer’s bill, changed substantially from a more ambitious reform effort last year, would allow lawmakers to appear as though they are doing something on the issue without backing wholesale changes.

But the more significant hurdle to ambitious reform is Newsom’s reticence to back policy shifts these lawmakers want, even as he pushes a rehabilitation-focused model of incarceration.

“This issue has made a lot of progress in the last decade,” said Hamid Yazdan Panah of Immigrant Defense Advocates, a member of the coalition backing the bill restricting solitary confinement. “It’s universally acknowledged that solitary confinement is a harmful practice that should be limited, particularly with respect to the length of time that it’s used.

“So from our perspective,” he said, “It’s a waiting game.”

No solitary confinement definition

California does not have a widely accepted definition of solitary confinement as it is used in correctional facilities.

CDCR’s “restricted housing” is used to isolate inmates from those in the general population, and those living inside the units typically have very limited contact with other people, although some do have cellmates. They are allowed out of their cells only for short periods of time.

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners rules defines solitary confinement as “confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.” The rules consider isolation beyond 15 days to be torture.

Holden’s bill defines solitary confinement as lasting more than 17 hours per day with “restricted activity, movement, or minimal or no contact with persons other than custodial staff.”

CDCR insists its facilities do not use solitary confinement. The agency does not explain how its restricted housing units differ from solitary confinement, saying only that inmates have access to “a minimum of 20 hours (per week) outside their cells and have the opportunity for meaningful activities including programming and non-contact visits,” according to Terri Hardy, a CDCR spokeswoman.

Prisoners can be placed in restricted housing for various reasons, including threats to others, discipline and protective custody.

When asked about Glazer’s bill, Hardy said in an email CDCR does not comment on pending legislation. She referred The Sacramento Bee to an agency dashboard with information on the prison population by security level and said CDCR will “comply with all tracking and reporting as legislatively mandated.”

Newsom won’t back substantial changes

Holden and Glazer’s bills are stymied by Newsom’s hesitance to make large-scale changes to California’s solitary confinement policy.

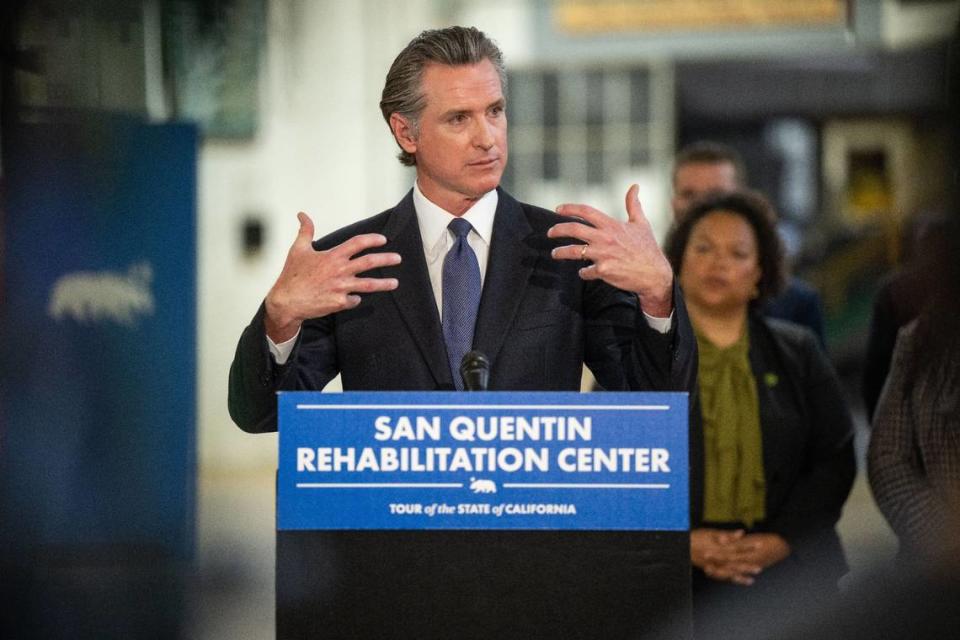

The governor has spent a significant amount of money and political capital to implement a new rehabilitation-focused model of incarceration at San Quentin State Prison in Marin County. Last year, he announced he wants to spend more than $380 million to revamp the prison into a rehabilitation center by 2025. His vision is modeled after Norwegian facilities that emphasize services and support instead of punishment.

But Newsom has declined to make similarly bold changes to the state’s use of inmate isolation.

The governor vetoed a 2022 version of Holden’s bill restricting solitary confinement, citing safety and cost concerns in his veto message. However, he called inmate isolation “ripe for reform” and directed CDCR to develop new solitary confinement regulations.

Last year, Holden authored a new version of the bill Newsom declined to sign. The lawmaker ended up holding the measure in the Assembly during the last few days of the legislative year.

After the session ended, CDCR announced emergency changes to its solitary confinement policy that were significantly less far-reaching than those in Holden’s bill.

They give inmates a minimum of 20 hours of outside cell time per week, up from the 10-hour minimum they previously received. The changes allow inmates in solitary to participate in additional rehabilitative programming and shave time off their isolation by earning credits.

They also limit the disciplinary offenses that land someone in solitary to those involving threats or violence, and they halve the amount of isolation time for prisoners accused of committing them.

The regulations do not provide many of the changes advocates and lawmakers have pushed, including limits on the amount of time prisoners can spend in solitary confinement and a ban on the practice for certain vulnerable groups of people.

Hardy said the new regulations align with Newsom’s veto message. “CDCR’s new restricted housing emergency regulations seek a better balance of safety, security and rehabilitation,” she said in an email.

The governor’s office declined requests to make a member of his administration available for an interview about Newsom’s solitary confinement policy. Izzy Gardon, a Newsom spokesman, referred The Sacramento Bee to the governor’s 2022 veto message.

Lawmakers back different reforms

The turmoil over the issue is also apparent in the legislature. Holden and Glazer are at odds over their approaches to solitary confinement policy.

Glazer’s bill, which collects data on the practice, is a rewritten version of a 2023 measure that would have enshrined in law a 2015 court settlement between solitary confinement inmates and CDCR.

“I’m trying to find some balance, some progress points,” Glazer said during a Senate Public Safety Committee hearing in 2023. “I know what you all would like, what everyone would like. But it’s an attempt to at least establish some foundation of progress as we try to go further.”

During that hearing, lawmakers on the committee told the senator his bill did not place enough restrictions on the practice of solitary confinement.

“While we can’t force the governor to sign something into law, we can continue to put something on his desk that reflects what we think is the appropriate policy,” said Sen. Nancy Skinner, D-Berkeley.

Earlier this month, committee members advanced the new version of Glazer’s bill, which deals with data collection, over the objections of Immigrant Defense Advocates and other supporters of Holden’s bill.

Those who voted in favor of Glazer’s data-collection measure said they did not think it would affect the movement to create systemic solitary confinement changes, which lawmakers still want to see.

“My bill is a significant step forward,” Glazer said in an interview. “Not everything that they want, but it’s a building block to get to where they want to go, which is to add some substantive reason to put these types of restrictions on our correctional institutions.”

Holden said in an interview he is “really trying to figure out how we can engage with the governor’s office,” with a focus on “additional areas that are worth exploring.”

He sees Glazer’s bill as one that says, “instead of taking major steps, we just want to take small, incremental steps that maybe aren’t even seen or measured when people start looking at the final results of things.”

“I’d like to think that, again, California doesn’t operate that way,” Holden said.

“Our current governor came in and said, ‘I don’t even need legislation. Executive order: no more death penalty,’” he added, referring to the governor’s 2019 decision to place a moratorium on the death penalty.

“That’s what we’re about,” Holden said. “I’d like to see that continue.”